Barbican, London

24 November

We were at the Barbican tonight to attend a selection of silent films being screened as part of the Irish Film Festival of London. Marking the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising, the evening comprised a series of short films selected by the Irish Film Institute tracing the history of Anglo-Irish historical and cultural dialogue during the revolutionary period and beyond. The event was introduced by Sunniva O’Flynn, Head of Irish Film Programming at the Irish Film Institute. Live musical accompaniment was provided by Cormac de Barra, Colm Ó Snodaigh and Rossa Ó Snodaigh.

First up were a series of films shot by cinema pioneers Sagar Mitchell and James Kenyon. We had a gentle ride in a horse drawn tram along the main streets of Belfast in 1901. The excellently preserved film showed what looked to be a prosperous Edwardian city. The citizens were well dressed and, apart from the destination boards on the other trams, it would have been difficult to place the location, Belfast probably looking little different from any other British city of the time. Of particular interest were the mobile advertising boards being wheeled down the road

First up were a series of films shot by cinema pioneers Sagar Mitchell and James Kenyon. We had a gentle ride in a horse drawn tram along the main streets of Belfast in 1901. The excellently preserved film showed what looked to be a prosperous Edwardian city. The citizens were well dressed and, apart from the destination boards on the other trams, it would have been difficult to place the location, Belfast probably looking little different from any other British city of the time. Of particular interest were the mobile advertising boards being wheeled down the road  advertising the screening of the actual film then being filmed from the tram. Next was footage shot in Cork showing the return of the Munster Fusiliers at the conclusion of the Boer War. The khaki uniforms probably reflect the lessons learned in the conflict and, while the soldiers not surprisingly appear rather glad to be back, the awaiting crowd seem curiously restrained. We then had a journey from Blarney to Cork on the Cork-Muskerry Light Railway filmed in 1902. Lastly was some 1901 footage of the congregation leaving St Mary’s Pro-Cathedral in Dublin. Despite, or perhaps because of, damage to the film stock this footage had a curious beauty, appearing almost as a complex montage of images of individuals all merging into each other as they passed across the screen.

advertising the screening of the actual film then being filmed from the tram. Next was footage shot in Cork showing the return of the Munster Fusiliers at the conclusion of the Boer War. The khaki uniforms probably reflect the lessons learned in the conflict and, while the soldiers not surprisingly appear rather glad to be back, the awaiting crowd seem curiously restrained. We then had a journey from Blarney to Cork on the Cork-Muskerry Light Railway filmed in 1902. Lastly was some 1901 footage of the congregation leaving St Mary’s Pro-Cathedral in Dublin. Despite, or perhaps because of, damage to the film stock this footage had a curious beauty, appearing almost as a complex montage of images of individuals all merging into each other as they passed across the screen.

(NB These films are all available on a BFI DVD/Blu-Ray ‘ Mitchell and Kenyon in Ireland’. They can also be viewed online. )

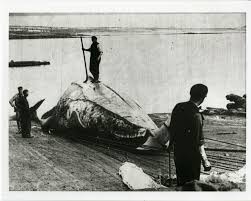

We then had a short film shot in 1908 by another early cinema pioneer, R W Paul, called Whaling: Afloat and Ashore which chronicled the activities of a Norwegian whaling company based in County Mayo in Western Ireland. We initially see the whalers at sea, harpooning their catch (and graphically depicting the awful barbarity of the business). Once back in port the

We then had a short film shot in 1908 by another early cinema pioneer, R W Paul, called Whaling: Afloat and Ashore which chronicled the activities of a Norwegian whaling company based in County Mayo in Western Ireland. We initially see the whalers at sea, harpooning their catch (and graphically depicting the awful barbarity of the business). Once back in port the whale carcasses are hauled ashore and systematically rendered down. It is only when the work is done that the film takes on a lighter note, showing the whalers at play, dancing, sack racing, wrestling and a somewhat curious game of throwing a small child about! This is such a beautifully shot and preserved film it’s hard to believe that it’s well over 100 years old and is apparently the earliest documentary made in Ireland. A step forward from the earlier Mitchell and Kenyon films which rather crudely just recorded what they saw, this is a more sophisticated film, well edited to document a specific activity from start to finish.

whale carcasses are hauled ashore and systematically rendered down. It is only when the work is done that the film takes on a lighter note, showing the whalers at play, dancing, sack racing, wrestling and a somewhat curious game of throwing a small child about! This is such a beautifully shot and preserved film it’s hard to believe that it’s well over 100 years old and is apparently the earliest documentary made in Ireland. A step forward from the earlier Mitchell and Kenyon films which rather crudely just recorded what they saw, this is a more sophisticated film, well edited to document a specific activity from start to finish.

(NB The film is available as part of a BFI compilation DVD on the films of R W Paul. It can also be viewed on-line.)

Next up was a film from Britain’s Imperial War Museum showing the lead-up to and physical consequences of the 1916 Easter rising in Dublin. There was footage of Republican volunteers parading and exercising, both in and out of uniform. After the uprising had been put down we saw footage of the level of damage sustained in the city with whole streets burnt out or reduced to rubble, damaged buildings being torn down, the locals looking on as British and ANZAC soldiers keep guard, soldiers loading a machine gun for the benefit of the cameras, what looked like an armoured truck on the move as well as British soldiers being treated in hospital. Probably telling the story from an |English perspective this film, although in poor condition, does succeed in highlighting the sheer physical devastation resulting from the uprising.

Next up was a film from Britain’s Imperial War Museum showing the lead-up to and physical consequences of the 1916 Easter rising in Dublin. There was footage of Republican volunteers parading and exercising, both in and out of uniform. After the uprising had been put down we saw footage of the level of damage sustained in the city with whole streets burnt out or reduced to rubble, damaged buildings being torn down, the locals looking on as British and ANZAC soldiers keep guard, soldiers loading a machine gun for the benefit of the cameras, what looked like an armoured truck on the move as well as British soldiers being treated in hospital. Probably telling the story from an |English perspective this film, although in poor condition, does succeed in highlighting the sheer physical devastation resulting from the uprising.

(NB A slightly different version of this footage is available on the BFI-player.)

Lastly amongst these short films was a rather curious 1922 movie, something of a mish-mash of news and travelogue, with scenes from around Ireland featuring the Powerscourt Country Estate with its gardens and waterfall; British soldiers leaving Ireland following the establishment of the Free State; and some rather wooden footage showing new President William T Cosgrave ‘at home with his family’ (only his rather aged mother looks even remotely comfortable in front of the camera). The film ends even more bizarrely with various shots of flowers dissolving into shots of attractive Irish ‘colleens’. All very interesting but just a bit odd!

(NB No sign of this film being available in any format)

We then had what was effectively the main feature of the evening, or at least the surviving footage from it. Some Say Chance (1934) was a silent film written and directed by Irish writer and amateur film-maker Michael Farrell. Some sources give the original film a running time of 45 minutes. Although a version of it had a limited cinema release in Dublin it is not clear whether this version was ever complete and it is now anyway considered lost. However, some elements of the film in the form of two 400ft reels plus seven cans of rushes are in the possession of the Irish Film Institute. From these, film-maker and IFI film programmer Dean Kavanagh was tasked this year with attempting to rebuild fragments of the original narrative

We then had what was effectively the main feature of the evening, or at least the surviving footage from it. Some Say Chance (1934) was a silent film written and directed by Irish writer and amateur film-maker Michael Farrell. Some sources give the original film a running time of 45 minutes. Although a version of it had a limited cinema release in Dublin it is not clear whether this version was ever complete and it is now anyway considered lost. However, some elements of the film in the form of two 400ft reels plus seven cans of rushes are in the possession of the Irish Film Institute. From these, film-maker and IFI film programmer Dean Kavanagh was tasked this year with attempting to rebuild fragments of the original narrative

The film itself tells the story of a young girl who is sent to a harsh and repressive boarding school believing her mother to be dead and while her father is away working in Australia. However, her mother is in fact alive and working in London as a penniless prostitute, ‘Irish Moll’. When Moll’s pimp discovers letters from her estranged husband he sees the prospect of making money from this knowledge. Unfortunately, this is where the surviving footage runs out. According to Kavanagh “In the end the mother actually dies, the father returns and kills the pimp, and finally reunites with his daughter, freeing her from the oppressive boarding school. Unfortunately none of this happy ending has survived, and so I took delectation in wallowing in the grim, frightened and naive fragments of the film that remained. Naturally”.

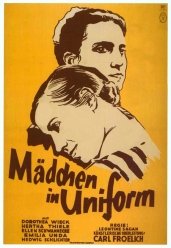

Even just the re-edited surviving fragments of Some Say Chance present a rather disconcerting film. There is a disquieting focus on schoolgirls variously in uniform, in their gym gear and in swimming costumes while the teaching staff have a strongly sadistic approach to education! There is  certainly an element of voyeurism in the film’s direction, if not a full blown fetish. Clear parallels could certainly be drawn with German cult classic Madchen in Uniform (Dir. Leontine Sagan, 1931) about

certainly an element of voyeurism in the film’s direction, if not a full blown fetish. Clear parallels could certainly be drawn with German cult classic Madchen in Uniform (Dir. Leontine Sagan, 1931) about  relationships between staff and pupils at a similarly strict girl’s boarding school.

relationships between staff and pupils at a similarly strict girl’s boarding school.

Although shot on a shoestring budget and with a very amateur feel to it, Some Say Chance does have a couple of specific points of interest. Writer/Director Farrell would go on in 1935 to be co-cinematographer of the much better and better known Irish silent Guests of the Nation (Dir. Dennis Johnston, 1935) a tense melodrama about two English soldiers held prisoner by the IRA. In addition, actress Rita FitzSimons who played Irish Moll managed to get her daughter Maureen an un-credited minor role in the film. Some years later, Maureen FitzSimons would change her name to Maureen O’Hara and her career never looked back!

(NB Some Say Chance is not available on DVD or online. It was even a struggle finding a still.)

Overall this evening was something of a mixed bag. Most impressive was the whaling footage from R W Paul, some of the Mitchell and Kenyon footage and the post-uprising scenes of Dublin. The attempt to reassemble what survived of the feature Some Say Chance was an interesting and noteworthy endeavour but I’m not sure that the end-result justified the effort. The narrative remained largely incomplete, there could be no escaping the production’s rather amateur feel and the film had a decidedly creepy, voyeuristic feel to it.

But the really standout feature of the evening was the musical accompaniment from harpist Cormac de Barra and brothers Colm and Rossa Ó Snodaigh who played everything else including tin whistle, flute, clarinet, mandolin, guitar, Jew’s harp, percussion and vocals. Their accompaniment especially to the whaling film was just superb, you could almost smell the sea air and the change in tone from the rather melancholy cutting up of the whales to the sight of the whalers at play was flawless. In the scenes of the devastation in Dublin in 1916 their music perfectly captured the tragedy of the situation and their playing beautifully complemented the Mitchell and Kenyon films, particularly the tram shots of Belfast and the troops returning home. I was a little less sure of their accompaniment to Some Say Chance but this was a difficult film to follow let alone accompany, with lots of repetition and only limited sense of where the story was going. If nothing else, the evening served to whet my appetite for more of this trio’s music.