The Barbican, London

23 April 2017

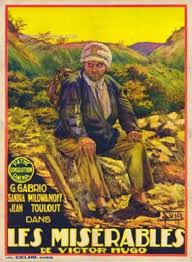

It may have been London Marathon day outside, but here inside at the Barbican we had a cinematic marathon of our own which was about to begin, with a screening of director Henri Fescourt,’s 1925 version of Les Miserables, all 397 minutes of it! And if that wasn’t enough, today’s screening would also be a somewhat

It may have been London Marathon day outside, but here inside at the Barbican we had a cinematic marathon of our own which was about to begin, with a screening of director Henri Fescourt,’s 1925 version of Les Miserables, all 397 minutes of it! And if that wasn’t enough, today’s screening would also be a somewhat  surprising premier, the first time that the full length film had ever been shown in the UK.

surprising premier, the first time that the full length film had ever been shown in the UK.

Based upon Victor Hugo’s epic 1862 novel, the story is centred upon the character of Jean Valjean (Gabriel Gabrio, left), a released convict, together with a disparate group of characters whose paths cross and re-cross over the course of some 15 years. The film begins with Valjean stealing the silverware from a benevolent bishop (left) who has given him shelter. When he is arrested, the Bishop inexplicably says the silver wasn’t stolen but was a gift for Valjean and he is  released. Valjean then conceals his identity and his past as he uses the stolen silver to become a successful businessman and eventually mayor. But he arouses the suspicion of police chief Javert (Jean Toulout, below right) who was a prison guard when Valjean was a convict and thinks he recognises him. Eventually his identity is revealed and he is forced to flee. Valjean then rescues Cosette, the child of one of his former employees who is being held as a virtual slave by unscrupulous innkeeper Thenardier (Georges Saillard) and his wife. In Paris, years pass as

released. Valjean then conceals his identity and his past as he uses the stolen silver to become a successful businessman and eventually mayor. But he arouses the suspicion of police chief Javert (Jean Toulout, below right) who was a prison guard when Valjean was a convict and thinks he recognises him. Eventually his identity is revealed and he is forced to flee. Valjean then rescues Cosette, the child of one of his former employees who is being held as a virtual slave by unscrupulous innkeeper Thenardier (Georges Saillard) and his wife. In Paris, years pass as  Valjean and Cosette live as father and daughter until she falls in love with Marius Pontmercy (Francois Rozet). The now destitute Thenardiers are also now in Paris attempting various money making scams assisted by their two daughters, Eponine (Suzanne Nivette) and Azelma.

Valjean and Cosette live as father and daughter until she falls in love with Marius Pontmercy (Francois Rozet). The now destitute Thenardiers are also now in Paris attempting various money making scams assisted by their two daughters, Eponine (Suzanne Nivette) and Azelma.

While begging money from Marius, Eponine becomes besotted with him. But when Marius discovers the Thenardier’s plans to scam and eventually kill a rich benefactor and his daughter (actually Valjean and Cosette) he goes to the police where Javert now works. The Thenardiers are arrested but Valjean escapes before his identity is revealed to Javert. After the Thenardiers  themselves escape prison, Eponine (now aware of Marius and Cosette’s feelings for each other) prevents the family from raiding Cosette and Valjean’s house.

themselves escape prison, Eponine (now aware of Marius and Cosette’s feelings for each other) prevents the family from raiding Cosette and Valjean’s house.

Rising political tensions in Paris lead to open rebellion against the government. Barricades are erected and Javert is identified by the revolutionaries as a police spy and captured. Marius joins the revolutionaries and as troops storm the barricades Eponine is killed saving his life. Valjean also sides with the revolutionaries. He volunteers to execute Javert but instead of shooting him he fires in the air and lets him go. Valjean then rescues the by now injured and unconscious Marius. As they escape they encounter Javert once again but he is torn between his  strict belief in upholding the law and his debt to Javert for saving his life. Unable to reconcile these two positions he lets Valjean escape and commits suicide.

strict belief in upholding the law and his debt to Javert for saving his life. Unable to reconcile these two positions he lets Valjean escape and commits suicide.

Marius, recovering from his injuries, marries Cosette but when Valjean reveals his criminal past Marius (also thinking that Valjean murdered Javert) seeks to distance himself and his wife from him leading Valjean to retreat to his house and give up the will to live. Thenardier eventually reappears with one last scam during which Marius discovers both that it was Valjean who saved his own life and that he also let Javert go free. Marius and Cosette rush to Valjean’s house and are reconciled with him just before he dies.

The above synopsis of a near seven-hour film, based upon a book of 365 chapters in 5 volumes, can clearly present only the barest outline of what is a complex and multi-strand story. And while the idea of a seven-hour film may be a little daunting, its sheer length is in many ways its greatest strength because it gives time to do justice to Hugo’s masterpiece. This is not some cut down, ninety-minute pastiche, focusing upon one or two key highlights, this is a near complete dramatisation of the book, in all its complex plot detail and wealth of cast.

Despite its scale and complexity, Les Miserables has been the subject of numerous adaptions, on film, radio, stage-play, musical, even manga comic! There have been over fifty film adaptions alone. The first was in 1897, a now

Despite its scale and complexity, Les Miserables has been the subject of numerous adaptions, on film, radio, stage-play, musical, even manga comic! There have been over fifty film adaptions alone. The first was in 1897, a now  lost film by the Lumier brothers. Another version came in 1909 from American film pioneer Edwin S Porter and a version was produced in Japan as early as 1910. The first feature length version was from France in 1912 directed by Alberto Cappellani and much praised in its time. Another much feted French version came from director Raymond Bernard in 1934. Hollywood got in on the act

lost film by the Lumier brothers. Another version came in 1909 from American film pioneer Edwin S Porter and a version was produced in Japan as early as 1910. The first feature length version was from France in 1912 directed by Alberto Cappellani and much praised in its time. Another much feted French version came from director Raymond Bernard in 1934. Hollywood got in on the act  in 1935 with a version starring Fredric March and Charles Laughton. Further French versions followed in 1958 with Jean Gabin and 1995 starring Jean Paul Belmondo, while Hollywood renewed its interest in 1998 with a vehicle for Liam Neeson and a musical version in 2012 with Hugh Jackman and Russell Crowe (!).

in 1935 with a version starring Fredric March and Charles Laughton. Further French versions followed in 1958 with Jean Gabin and 1995 starring Jean Paul Belmondo, while Hollywood renewed its interest in 1998 with a vehicle for Liam Neeson and a musical version in 2012 with Hugh Jackman and Russell Crowe (!).

But amongst these various adaptions, the one that went virtually unseen in its original form since its first release was Fescourt’s 1925 version. It was originally produced in a fully tinted seven-hour version. Despite being a resounding critical and public success at the time, this original version largely disappeared from view, to be replaced by a much shorter black and white edit. The original version was never ‘lost’; it merely languished in various film vaults. But this all changed in late 2014 when, following a four-year restoration process, the film was screened in its original tinted and full length version and in 2015 it got a showing at the Pordenone silent film festival.

Born in 1880, the son of a high school teacher, Fescourt (right) studied law, worked as a music critic and  then as a trainee journalist before starting his cinema career as a screenwriter for the Gaumont studio in in 1911. He quickly moved on to directing, producing some sixty shorts before heading off for war service in 1915. In the early 1920s he began a series of films based upon the works of great French authors. His first major success was Mathias Sandorf (1921) based on the novel by Jules verne. Then came Les Miserables in 1925 and his last big success was 1929’s Monte Cristo based on the novel by Alexandre Dumas. Although Fescourt continued to

then as a trainee journalist before starting his cinema career as a screenwriter for the Gaumont studio in in 1911. He quickly moved on to directing, producing some sixty shorts before heading off for war service in 1915. In the early 1920s he began a series of films based upon the works of great French authors. His first major success was Mathias Sandorf (1921) based on the novel by Jules verne. Then came Les Miserables in 1925 and his last big success was 1929’s Monte Cristo based on the novel by Alexandre Dumas. Although Fescourt continued to  direct films in the sound era, these achieved little popular or critical success and by 1943 he had retired from active film making. Instead, he took up a series of academic posts in the techniques of film production. He wrote a biography ‘Faith and the Mountains’ in 1959 and died in 1966.

direct films in the sound era, these achieved little popular or critical success and by 1943 he had retired from active film making. Instead, he took up a series of academic posts in the techniques of film production. He wrote a biography ‘Faith and the Mountains’ in 1959 and died in 1966.

Fescourt’s work is generally under-rated and largely forgotten today, a result, it has been argued, of his output being focused mainly on film serials (cineromans) which although popular were scorned by intellectuals. But Fescourt’s experience in turning out multi-episode serials often with complex and long drawn-out plot structures and his willingness to devote sufficient screen time to telling Hugo’s complex story is probably a key reason in ensuring his version of Les Miserables was a success, enabling his seven hour film to follow a lucid and cogent plot which captured the essential spirit of Hugo’s writing and avoided being just a series of largely unconnected tableaux highlighting key points of the book. So, despite the plethora of Les Miserables adaptions around, amongst those who have been lucky enough to see this restored version “…it is not too much to surmise that Henri Fescourt’s 1925 cinéroman is the most faithful in every sense – to the narrative, the philosophy, the humanity, and the morality. This is Hugo.” D.Robinson.

As well as being a faithful adaption of Hugo’s novel, Les Miserables is also a visual feast. Compared to the low quality black and white version which can be viewed online, the restored version is a revelation, superbly brought to life by the Cinémathèque de Toulouse, the Center National de la Cinématographie and the Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé

As well as being a faithful adaption of Hugo’s novel, Les Miserables is also a visual feast. Compared to the low quality black and white version which can be viewed online, the restored version is a revelation, superbly brought to life by the Cinémathèque de Toulouse, the Center National de la Cinématographie and the Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé  Foundation. The images are beautifully clear and crisp, much of the picture looked like it could have been filmed yesterday and the tinting and toning give the film a sumptuous colour. A significant proportion was shot on location, particularly in the channel village of Montreuil-sur-Mer (right), where Hugo set the original story and which had probably not changed significantly since he first visited it in the 1830s, giving the film a hugely authentic feel. Even where studio sets were employed, particularly in the Paris street scenes and various interiors, these impressed through

Foundation. The images are beautifully clear and crisp, much of the picture looked like it could have been filmed yesterday and the tinting and toning give the film a sumptuous colour. A significant proportion was shot on location, particularly in the channel village of Montreuil-sur-Mer (right), where Hugo set the original story and which had probably not changed significantly since he first visited it in the 1830s, giving the film a hugely authentic feel. Even where studio sets were employed, particularly in the Paris street scenes and various interiors, these impressed through

their realism. Fescourt made sparing use of special effects but these were employed to very dramatic effect in the scene of the young Cosette being sent out into the night to fetch water, with wild animals and the face of Mme Thenardier looming out from the trees to terrify the child, while the very trees themselves appeared as if coming to life (left). Also breath-taking was the short scene of the battlefield of Waterloo as

their realism. Fescourt made sparing use of special effects but these were employed to very dramatic effect in the scene of the young Cosette being sent out into the night to fetch water, with wild animals and the face of Mme Thenardier looming out from the trees to terrify the child, while the very trees themselves appeared as if coming to life (left). Also breath-taking was the short scene of the battlefield of Waterloo as  Thenardier loots the bodies of the dead, resembling more a carefully composed oil painting than a film set, it’s a beautiful mix of live action foreground and painted backdrop (right), perfectly capturing the scale of the slaughter. And while much of the film takes place at an intimate level, in scenes which Fescourt handles superbly, he is equally adept at handling the more dramatic and larger scale moments such as the ballroom scene or the street-fighting on the barricades.

Thenardier loots the bodies of the dead, resembling more a carefully composed oil painting than a film set, it’s a beautiful mix of live action foreground and painted backdrop (right), perfectly capturing the scale of the slaughter. And while much of the film takes place at an intimate level, in scenes which Fescourt handles superbly, he is equally adept at handling the more dramatic and larger scale moments such as the ballroom scene or the street-fighting on the barricades.

As well as Fescourt’s direction, the film’s success is also a reflection of the uniformly high quality of the acting. Les Miserables was unusual in that Fescourt cast it without any recognised stars. Gabriel Gabrio puts in a solid performance as Valjean (left), in some ways reminiscent of Gerard Depardieu, a lumbering figure who mellows from bitter convict to heroic figure, eventually finding redemption for his long-ago petty crime.

As well as Fescourt’s direction, the film’s success is also a reflection of the uniformly high quality of the acting. Les Miserables was unusual in that Fescourt cast it without any recognised stars. Gabriel Gabrio puts in a solid performance as Valjean (left), in some ways reminiscent of Gerard Depardieu, a lumbering figure who mellows from bitter convict to heroic figure, eventually finding redemption for his long-ago petty crime.  Gabrio would continue making films into the 1940s, although never again achieving a star role. Amongst subsequent roles he is perhaps best remembered as second lead to Jean Gabin in Pepe le Moke (1937). Jean Toulout is convincing also as the stiff and upright Javert, unable to reconcile his duty with his debt to Valjean. He would go on to appear in Fescourt’s Monte Cristo (1929) and had made over 100 films before his retirement in 1952. Although Russian-born Sandra Milowanoff was excellent as Fantine, the determined single-mother of Cosette (right), she was less convincing in the dual role of the adult Cosette. Milowanoff was already a

Gabrio would continue making films into the 1940s, although never again achieving a star role. Amongst subsequent roles he is perhaps best remembered as second lead to Jean Gabin in Pepe le Moke (1937). Jean Toulout is convincing also as the stiff and upright Javert, unable to reconcile his duty with his debt to Valjean. He would go on to appear in Fescourt’s Monte Cristo (1929) and had made over 100 films before his retirement in 1952. Although Russian-born Sandra Milowanoff was excellent as Fantine, the determined single-mother of Cosette (right), she was less convincing in the dual role of the adult Cosette. Milowanoff was already a  regular in Fescourt films before Les Miserables and afterwards went on to starring roles in a string of European silent films but she failed to make the transition to talkies and died, largely forgotten, in 1964.

regular in Fescourt films before Les Miserables and afterwards went on to starring roles in a string of European silent films but she failed to make the transition to talkies and died, largely forgotten, in 1964.

However, it was some of the lesser cast members who particularly excelled. Child actress Andree Rolane was astonishing as the young Cosette (above left), utterly convincing in  her portrayl of the terror of living in the Thenardier household and particularly so as she was cast out into the night to fetch water. The scenes where she quietly took the Thenardier child’s doll to play with or when Valjean brought her a doll of her own (right) were almost too heart-breaking to watch. Other than appearances in two other films in the mid-1920s I can find out nothing more about her but would grateful to learn more about her. However, greatest praise goes to Suzanne Nivette as the adult Eponine (below left, a very poor picture but the only one I could find) in what was a superb performance, physically capturing the gaunt and

her portrayl of the terror of living in the Thenardier household and particularly so as she was cast out into the night to fetch water. The scenes where she quietly took the Thenardier child’s doll to play with or when Valjean brought her a doll of her own (right) were almost too heart-breaking to watch. Other than appearances in two other films in the mid-1920s I can find out nothing more about her but would grateful to learn more about her. However, greatest praise goes to Suzanne Nivette as the adult Eponine (below left, a very poor picture but the only one I could find) in what was a superb performance, physically capturing the gaunt and  dead-eyed look of someone living by their wits but at the brink of starvation yet at the same time beautifully portraying both that feel of unrequited love as she becomes besotted with Marius and of the hopelessness of her own situation as she realises that he is in love with someone else. That her sacrifice of her own life to save that of Marius also goes un-noticed makes it all the more tragic although her redemption of sorts comes with a kiss from Marius on her dying forehead. Married at the time to Les Miserables co-star Georges Saillard (Thenardier) this may well have been Nivette’s first film role. She continued film acting until her retirement in 1960, including a 1958 remake of Les Miserables in which she played Mme

dead-eyed look of someone living by their wits but at the brink of starvation yet at the same time beautifully portraying both that feel of unrequited love as she becomes besotted with Marius and of the hopelessness of her own situation as she realises that he is in love with someone else. That her sacrifice of her own life to save that of Marius also goes un-noticed makes it all the more tragic although her redemption of sorts comes with a kiss from Marius on her dying forehead. Married at the time to Les Miserables co-star Georges Saillard (Thenardier) this may well have been Nivette’s first film role. She continued film acting until her retirement in 1960, including a 1958 remake of Les Miserables in which she played Mme  Gillenormand and she died in 1995 at the grand old age of 100.

Gillenormand and she died in 1995 at the grand old age of 100.

Although there has been talk of a DVD/Blu-Ray release of Les Miserables, there is as yet no sign of this appearing. Given the quality both of Fescourt’s original film and the  recent restoration work it would be a tragedy if this did not happen. This is a film which cries out for wider recognition and repeated viewings.

recent restoration work it would be a tragedy if this did not happen. This is a film which cries out for wider recognition and repeated viewings.

Finally, a word about the live piano accompaniment from Neil Brand. Although set something of a marathon task, this was clearly a labour of love for Mr Brand and he accomplished it superbly, matching rhythm and tone perfectly with the events unfolding on screen and adding immeasurably to enjoyment of the film. Even after six hours playing he was able to up the tempo to match the drama of unfolding revolution and its aftermath. Clearly a gold medal effort. Lastly a word of thanks to the other live accompaniment, the provision of on-screen translations of the French inter-titles. While the occasional use of phrases such as ‘you guys’ and ‘oddball’ didn’t necessarily have the authentic ring of Hugo-ish language, this was nevertheless also a superb effort, especially for a near seven hour long film.