Kennington Bioscope at the Cinema Museum, Lambeth

14 September 2016

Following last week’s ‘Vitagraph 9.5mm – The Sequel’ special with Kevin Brownlow (see here for details), we are back at the Cinema Museum again tonight for the first regular Kennington Bioscope presentation of their Autumn season. The good news is that Kevin is also back to introduce tonight’s screenings. The main feature is The Mating Call (1928), but as always the evening begins with a full programme of support features.

Following last week’s ‘Vitagraph 9.5mm – The Sequel’ special with Kevin Brownlow (see here for details), we are back at the Cinema Museum again tonight for the first regular Kennington Bioscope presentation of their Autumn season. The good news is that Kevin is also back to introduce tonight’s screenings. The main feature is The Mating Call (1928), but as always the evening begins with a full programme of support features.

First up is The Ropin’ Fool (Dir. Clarence C Badger, 1922), a western….sort of….well, no, more an instructional video on lasso work. Will Rogers plays Ropes Reilly ‘The Ropin Fool’, a man so keen on lasso work that his hands continue spinning an imaginary noose even in his sleep (below, right) . Having been sacked from his job as a ranch hand he takes to ropin’ goats, geese, cats, dogs and even rats. The film is really an extended advert allowing Rogers to demonstrate his incredible lassoing skills (and they really are impressive!). The film makes early use of slow motion photography to very effectively highlight his ability. I’m not sure how they did this, presumably not through hand cranking the

First up is The Ropin’ Fool (Dir. Clarence C Badger, 1922), a western….sort of….well, no, more an instructional video on lasso work. Will Rogers plays Ropes Reilly ‘The Ropin Fool’, a man so keen on lasso work that his hands continue spinning an imaginary noose even in his sleep (below, right) . Having been sacked from his job as a ranch hand he takes to ropin’ goats, geese, cats, dogs and even rats. The film is really an extended advert allowing Rogers to demonstrate his incredible lassoing skills (and they really are impressive!). The film makes early use of slow motion photography to very effectively highlight his ability. I’m not sure how they did this, presumably not through hand cranking the camera at ten time’s normal speed! I assume it must have been achieved somehow in the developing stage but would welcome any more knowledgeable views.

camera at ten time’s normal speed! I assume it must have been achieved somehow in the developing stage but would welcome any more knowledgeable views.

The plot, such as it is, is confined to the final five minutes of the film and isn’t really worth the effort. Apart from the lassoing skills on show, the film is memorable for some good lines from the medicine  doctor who is trying to keep a crowd interested in his products in the face of the constant distraction of Rogers’ performance. His response when Rogers nonchalantly flicks his rope into a perfectly tied knot, “He’s no good. I had a brother once who died with a better knot than that, tied round his neck”, with lots more in a similar vein. Having achieved international renown as a cowboy, vaudeville performer, humorist, newspaper columnist, social commentator, and stage and motion picture actor, famous for his pithy and homespun humour, Rogers had successfully made the transition to sound films before sadly being killed in a plane crash in 1935 at the height of his fame. All in all, The Ropin’ Fool was fun but just a tad too much ropin’ for me.

doctor who is trying to keep a crowd interested in his products in the face of the constant distraction of Rogers’ performance. His response when Rogers nonchalantly flicks his rope into a perfectly tied knot, “He’s no good. I had a brother once who died with a better knot than that, tied round his neck”, with lots more in a similar vein. Having achieved international renown as a cowboy, vaudeville performer, humorist, newspaper columnist, social commentator, and stage and motion picture actor, famous for his pithy and homespun humour, Rogers had successfully made the transition to sound films before sadly being killed in a plane crash in 1935 at the height of his fame. All in all, The Ropin’ Fool was fun but just a tad too much ropin’ for me.

(NB The Ropin’ Fool appears to be available at Amazon on VHS (!) here and is watchable on-line at archive.org)

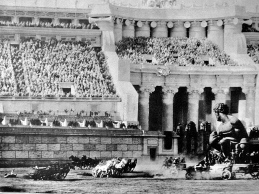

Next up, Kevin showed a short clip of the pre-chariot race parade from the earliest version of Ben-Hur (Dir. H T Morey, S Olcott & F Rose, 1907). This film has several points of interest (an early starring role for screen cowboy William S Hart, image below left), and as a film that set a precedent in copyright law, having been made without the author’s permission who then successfully sued) but sadly none of them are to do with the content of the film itself. In fact, Mr

Next up, Kevin showed a short clip of the pre-chariot race parade from the earliest version of Ben-Hur (Dir. H T Morey, S Olcott & F Rose, 1907). This film has several points of interest (an early starring role for screen cowboy William S Hart, image below left), and as a film that set a precedent in copyright law, having been made without the author’s permission who then successfully sued) but sadly none of them are to do with the content of the film itself. In fact, Mr  Brownlow made a good case for it being a fine example of how not to make an epic. The budget was minuscule (just $500 according to IMDb) and it showed in the tacky sets and costumes. The clip we saw didn’t extend to the actual chariot race but according to legend this was filmed on a beach in New Jersey with local firemen playing the charioteers and the horses that normally pulled the fire wagons pulling the chariots which simply ride in circles around a single static camera. (NB The whole film is viewable on-line at archive.org. )

Brownlow made a good case for it being a fine example of how not to make an epic. The budget was minuscule (just $500 according to IMDb) and it showed in the tacky sets and costumes. The clip we saw didn’t extend to the actual chariot race but according to legend this was filmed on a beach in New Jersey with local firemen playing the charioteers and the horses that normally pulled the fire wagons pulling the chariots which simply ride in circles around a single static camera. (NB The whole film is viewable on-line at archive.org. )

His purpose was to provide a contrast of how an epic should be made  by then showing a clip of the same pre-race parade from the 1925 version of Ben Hur (Dir. Fred Niblo) which never fails to astound with its cast of thousands and epically proportioned sets. But then, as a further clip, this time from his renowned Thames TV Hollywood series showed, all was not as it seemed. The upper tiers of the stadium were not real, instead they were carefully constructed miniatures, filled with

by then showing a clip of the same pre-race parade from the 1925 version of Ben Hur (Dir. Fred Niblo) which never fails to astound with its cast of thousands and epically proportioned sets. But then, as a further clip, this time from his renowned Thames TV Hollywood series showed, all was not as it seemed. The upper tiers of the stadium were not real, instead they were carefully constructed miniatures, filled with  moveable model spectators, which were skilfully positioned within the upper camera frame to perfectly mesh in with the full size sets below. The clip served not only to underline the genius of the silent film era in a time before CGI but also to emphasise the tragedy of the Hollywood series remaining unavailable on DVD/Blu-Ray.

moveable model spectators, which were skilfully positioned within the upper camera frame to perfectly mesh in with the full size sets below. The clip served not only to underline the genius of the silent film era in a time before CGI but also to emphasise the tragedy of the Hollywood series remaining unavailable on DVD/Blu-Ray.

Then, just for a treat, we got to see the whole chariot race sequence from the 1925 version. This remains one of the most stunning pieces of film making….ever! Forty plus cameras, 200,000ft of film shot then edited down to 750ft for the finished release. As good as anything Eisenstein was doing on the Odessa steps that same year. Yet, as ever with this scene, my only qualm is in scale of equine suffering. Not a production to which you could apply the epithet ‘No animals were harmed in the making of this film’! Its nice to think that in this respect film making has moved on.

(NB The 1925 version of Ben Hur is available at Amazon Here while the chariot race how-it-was-done clip from the Hollywood series is watchable on youtube.com )

Then it was time for the main feature, The Mating Call (Dir. James Cruz, 1928) one of the early successes from the Caddo Corporation, a film production company established by maverick millionaire industrialist Howard Hughes following his arrival in Hollywood in 1925. As well as limitless cash, Hughes brought with him a desire to challenge Hollywood orthodoxy in terms of profanity, violence and sexual situations, a quest that would repeatedly bring him into conflict not just the Old-Hollywood establishment but also with the censors and other arbiters of ‘taste’. The Mating Call is a perfect example of such a Hughes production. Long

Then it was time for the main feature, The Mating Call (Dir. James Cruz, 1928) one of the early successes from the Caddo Corporation, a film production company established by maverick millionaire industrialist Howard Hughes following his arrival in Hollywood in 1925. As well as limitless cash, Hughes brought with him a desire to challenge Hollywood orthodoxy in terms of profanity, violence and sexual situations, a quest that would repeatedly bring him into conflict not just the Old-Hollywood establishment but also with the censors and other arbiters of ‘taste’. The Mating Call is a perfect example of such a Hughes production. Long  thought lost, a copy of the film was discovered in the archives of Howard Hughes memorabilia by curators at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas and restored and re-released by Turner Classic Movies.

thought lost, a copy of the film was discovered in the archives of Howard Hughes memorabilia by curators at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas and restored and re-released by Turner Classic Movies.

The Mating Call opens with Leslie Hatton (Thomas Meighan) a decorated war hero, returning from World War I to find that the parents of his bride (whom he secretly married immediately before being shipped out) have had their marriage annulled. His now ex-wife Rose (Evelyn Brent) has subsequently married the more socially acceptable Lon Henderson (Alan Roscoe). But Henderson has an eye for the ladies and in frustration Rose returns hoping to resume her relationship with Hatton. Although clearly tempted, Hatton resists and literally throws Rose out. To avoid further approaches from Rose and the risk of antagonising Henderson who is also local head of ‘The Order’, a thinly disguised version of the Ku Klux Klan, which looks unfavourably on such ‘moral turpitude’ Henderson claims that he too got married while in Europe.

Klan, which looks unfavourably on such ‘moral turpitude’ Henderson claims that he too got married while in Europe.

To acquire such a wife Hatton now heads over to Ellis Island where an official directs him to Catherine (Renee Adoree) and her parents, poor would-be immigrants from Europe who are facing deportation. He offers to marry her in exchange for the family being allowed to settle in America. Her parents strongly oppose the bargain, but she accepts and they are married. On returning to his farm it is Hatton who is the more uncomfortable with the situation, choosing to spend the night alone rather than with his new wife.

Meanwhile Lon is seeking to end his relationship with his teenage mistress Jessie (Helen Foster), the daughter of Judge Peebles (Luke Cosgrave), but she refuses to hand over letters incriminating him in  this affair. When Jessie’s friend Marvin (Gardner James) asks her to marry him she wants time to think it over but secretly stashes the incriminating letters in his pocket. When Jessie is later found dead, Henderson in his role as head of ‘The Order’ pins the blame for her murder on Hatton and orders his seizure and ‘trial’.

this affair. When Jessie’s friend Marvin (Gardner James) asks her to marry him she wants time to think it over but secretly stashes the incriminating letters in his pocket. When Jessie is later found dead, Henderson in his role as head of ‘The Order’ pins the blame for her murder on Hatton and orders his seizure and ‘trial’.

At the farm, Hatton and his new wife are gradually developing genuine feelings for each other when he is seized by members of ‘The Order’, quickly tried, found guilty and sentenced to a whipping. But Henderson is then found shot dead in his office and Marvin is discovered there with a gun. He produces the letters incriminating Henderson and says he intended to kill him but that he found him already dead. Hatton is subsequently freed and men from ‘The Order’ arrange Henderson’s death to look like suicide. The final scene shows Judge Peebles, Jessie’s father, unloading and cleaning his gun. One cartridge has been discharged!

While The Mating Call may not be a great film it is certainly an enjoyable one and one which doesn’t so much challenge traditional Hollywood notions of decency and probity as drive a coach and horses through them. The characters of Henderson and Rose are clearly serial adulterers while the scenes between Hatton and Rose exude sexual intrigue. In one scene Rose enters his house, goes into the kitchen, and drenches herself with a basin of water so that she can force him to bring in her valise of clothes and use the accident as an excuse to shed her attire. And Catherine’s naked midnight swim certainly added to the films boundary-pushing reputation. Yet in contrast to the overt sexuality there is also a touching innocence, in particular between Hatton and Catherine, for example when he chooses to spend the night on the sofa rather than with her or when he insists that she too sits at the breakfast table with him as an equal rather than stand as a servant.

The film also offers up great contrasts, for example between notions of honour (Hatton forsaking Rose as a result of her previous behaviour towards him even though he still has strong feelings for her) and hypocrisy (Henderson being guilty of everything ‘The Order’ supposedly stands against) or between tradition (with Catherine doing the chores, being a good wife and loving her husband) and  modernity (with Rose, clear in what she wants from life and not afraid to go out and get it, irrespective of the consequences).

modernity (with Rose, clear in what she wants from life and not afraid to go out and get it, irrespective of the consequences).

Amongst the actors, Thomas Meighan (image, left) was clearly too old for the part but nevertheless put in a solid performance as the rugged hero. Meighan moved from the theatre to film making in 1915 and probably hit a career high with 1919’s The Miracle Man (Dir. George Loane Tucker) co-starring with Lon Chaney in a film now considered lost. At that time he was reportedly earning $10,000 per week. But his association with Howard Hughes resulted in a late renaissance in his career with The Racket (Dir. Lewis Milestone, 1928) and The Mating Call both critical and popular successes. Meighan never really made a successful transition to sound films although his efforts were also hampered by ill health and he died in 1936.

Renee Adoree (image, right) seemed to get particular critical acclaim in The Mating Call although it’s hard to see how as this wasn’t a particularly challenging role and, as one reviewer has remarked, it “differed little from the wide-eyed Euro damsels that were her trademark”. Perhaps it was as a result of her reputation, having previously starred in The Big Parade (Dir. King Vidor, 1925) opposite John Gilbert, one of the most successful and highly  acclaimed films of the silent era. Or perhaps it was just down to that nude midnight swim! Collected wisdom (ie Wikipedia and IMDb) says that Adoree was born in France but prior to this evening’s screening film historian Tony Fletcher revealed that this was probably incorrect, that she was in fact born in Germany to a British father and that she concealed her German origins so as not to harm her career. Adoree seemed to successfully make the transition to sound, starring in talkies with John Gilbert and Ramon Navarro but her career was curtailed by the onset of TB and she died in 1933

acclaimed films of the silent era. Or perhaps it was just down to that nude midnight swim! Collected wisdom (ie Wikipedia and IMDb) says that Adoree was born in France but prior to this evening’s screening film historian Tony Fletcher revealed that this was probably incorrect, that she was in fact born in Germany to a British father and that she concealed her German origins so as not to harm her career. Adoree seemed to successfully make the transition to sound, starring in talkies with John Gilbert and Ramon Navarro but her career was curtailed by the onset of TB and she died in 1933

To my mind, it was Evelyn Brent (image, left) who put in much the better performance as the sex-hungry Rose. This was a woman who knew what she wanted and would stop at nothing to get it. I particularly liked the scene where she smashed her way back through Hatton’s front door. This wasn’t a woman that was going to spend time mopping the floor or bathing the piglets (and I’m still not sure why Catherine was doing that!). Starting out in films in 1915, Brent’s career got a boost in 1922 when she was selected as a WAMPAS baby. She became a bankable star, putting in a number of fine performances. I particularly liked her as the revolutionary who falls in love with Emil Jannings in The Last Command (Dir Josef von Sternberg, 1928). Brent not only successfully made the transition to sound films but continued screen acting until she retired in 1950.

To my mind, it was Evelyn Brent (image, left) who put in much the better performance as the sex-hungry Rose. This was a woman who knew what she wanted and would stop at nothing to get it. I particularly liked the scene where she smashed her way back through Hatton’s front door. This wasn’t a woman that was going to spend time mopping the floor or bathing the piglets (and I’m still not sure why Catherine was doing that!). Starting out in films in 1915, Brent’s career got a boost in 1922 when she was selected as a WAMPAS baby. She became a bankable star, putting in a number of fine performances. I particularly liked her as the revolutionary who falls in love with Emil Jannings in The Last Command (Dir Josef von Sternberg, 1928). Brent not only successfully made the transition to sound films but continued screen acting until she retired in 1950.

Director James Cruz began his film career as an actor, making well over a hundred films by 1920 by which time he had already turned to directing. His output encompassed melodramas, comedies, westerns and gangster films including The Covered Wagon (1923), Merton of the Movies (1924), The City Gone Wild (1927) with Louise Brooks and The Great Gabbo (1929) with Erich von Stroheim.

(NB. The Mating Call is available to buy on DVD Here )

As usual, live accompaniment to the films was superb. Many thanks to pianists Meg Morley and Costas Fotopoulos for all their efforts.

As always, an excellent evening at the Kennington Bioscope. We learnt how to make an epic, how not to make an epic and how to use a lasso. More than that we got to see a fine example of pre-code melodrama, a film which positively oozed sex, deceit and hypocrisy. What more could you want of an evening.