Film Listings

At the end of another glorious year of silent film going its probably a good time to recap on the year as a whole and try to get a broader picture of silent film screening nationwide, particularly in comparison to 2016 when we compiled our first annual review (click here to read).

At the end of another glorious year of silent film going its probably a good time to recap on the year as a whole and try to get a broader picture of silent film screening nationwide, particularly in comparison to 2016 when we compiled our first annual review (click here to read).

During the course of 2017 silentfilmcalendar.org managed to record 714 silent film screenings across the country. This was a appreciable increase on the previous year’s 548. But its hard to gauge the significance of this rise. Does it mean that substantially more silent films are being screened or is it simply that we are getting better at listing those that are taking place. The answer probably lies somewhere between the two. Last year we estimated that we were aware of and listed around three quarters of silent film being screened nationwide. Although we have probably been more successful this year, there are still a considerable number of screenings that we become aware of only after the event and we remain largely unsighted about screenings in film clubs and societies. But assuming we now capture perhaps 80% of screenings that means the total number of silent films screened nationwide in 2017 probably significantly  exceeded 850, compared to around 700 the previous year.

exceeded 850, compared to around 700 the previous year.

So the pleasing conclusion may well be that our listings numbers are up at least partly because more silent films are being screened. Certainly the overall number of screenings this year was boosted by Eureka Video’s brave decision to mount ambitious theatrical re- releases of two of its restored silent features, Der Mude Tod (Dir. Fritz Lang, Ger, 1921) and Metropolis (Dir. Fritz Lang, Ger, 1927) as well as that rare thing, the wide release of a modern silent, London Symphony (Dir. Alex Barrett, UK, 2017).

releases of two of its restored silent features, Der Mude Tod (Dir. Fritz Lang, Ger, 1921) and Metropolis (Dir. Fritz Lang, Ger, 1927) as well as that rare thing, the wide release of a modern silent, London Symphony (Dir. Alex Barrett, UK, 2017).

Last year we attempted to estimate from the number of film screenings the total audience for silent films nationwide. Our estimate was based upon a judgement of an audience of around 150 per screening. In hindsight we now believe that to be  something of an overestimate. A more reasonable figure is considered to be around 100 people per screening, giving a total of around 85,000 ‘bums on seats’ for the year, a reduction from last year’s over-estimate of 100,000 but still a very respectable total.

something of an overestimate. A more reasonable figure is considered to be around 100 people per screening, giving a total of around 85,000 ‘bums on seats’ for the year, a reduction from last year’s over-estimate of 100,000 but still a very respectable total.

Looking at the figures from a regional perspective, silent film screenings in London continue to dominate the overall numbers but there are continuing signs of the rise of regional ‘strong points’ particularly around the Bristol area (thanks largely to the efforts of South West Silents) with some 36 screenings last year and in the central Yorkshire belt of Sheffield/Huddersfield/Halifax/Leeds (Yorkshire Silents playing a significant role here) with almost 50 screenings. The central belt of Scotland (Glasgow/Edinburgh including Bo’Ness) also accounted for some 50 screenings. There were also positive developments in the north of Scotland (Inverness/Orkney/Shetland) this year with ten screenings compared to just one last year. But other areas of the country sadly remain largely silent film free, particularly Wales, Northern Ireland and the East of England.

The Films

As well as an increase in the total number of film screenings from 2016 to 2017 there was also a significant increase in the number of different titles being screened. In the last year, 259 different films were screened, compared to only  197 in 2016. The most frequently shown film of the year was Der Mude Tod (Dir. Fritz Lang, Ger, 1921) with 80 screenings, followed by Metropolis (Dir. Fritz Lang, Ger, 1927) with 52 and London Symphony (Dir. Alex Barrett, UK, 2017) with 34 (but see footnote below). Last year’s most screened film, Battle of the Somme (Dir. Geoffrey Malins, UK, 1916) came fourth with 29 screenings (down from last year’s 51). Next came Phantom of the Opera (Dir. Rupert Julian, US, 1925) with 17,

197 in 2016. The most frequently shown film of the year was Der Mude Tod (Dir. Fritz Lang, Ger, 1921) with 80 screenings, followed by Metropolis (Dir. Fritz Lang, Ger, 1927) with 52 and London Symphony (Dir. Alex Barrett, UK, 2017) with 34 (but see footnote below). Last year’s most screened film, Battle of the Somme (Dir. Geoffrey Malins, UK, 1916) came fourth with 29 screenings (down from last year’s 51). Next came Phantom of the Opera (Dir. Rupert Julian, US, 1925) with 17, Nosferatu (Dir. F W Murnau, Ger, 1922) with 14 and The Lodger : A Story of the London Fog (Dir. Alfred Hitchcock, UK, 1927) with 13.

Nosferatu (Dir. F W Murnau, Ger, 1922) with 14 and The Lodger : A Story of the London Fog (Dir. Alfred Hitchcock, UK, 1927) with 13.

Top spots for Der Mude Tod and Metropolis were largely down to their theatrical re-release in main stream cinemas. Metropolis is a perennial favourite so its success on re-release was to be expected but Der Mud Tod is a fairly obscure early work from Lang, little known even among fans, so its selection for a big commercial push was a little surprising. It would be interesting to know what the audience figures were for its screenings. Although purely  anecdotal, on the two occasions we saw it there were less than 20 people in the auditorium. The danger is that if not as successful as anticipated it will deter the distributors attempting further silent film releases. We can but hope that this isn’t the case. London Symphony’s position probably owes a lot to a determined programming effort, often utilising non-traditional screening venues. Screenings of Battle of the Somme were part of a campaign by composer Laura Rossi to organise 100 screenings of the film with live orchestral accompaniment for her newly composed score in the 100th anniversary year of the actual battle. With 51 screenings in 2016 and 29 in

anecdotal, on the two occasions we saw it there were less than 20 people in the auditorium. The danger is that if not as successful as anticipated it will deter the distributors attempting further silent film releases. We can but hope that this isn’t the case. London Symphony’s position probably owes a lot to a determined programming effort, often utilising non-traditional screening venues. Screenings of Battle of the Somme were part of a campaign by composer Laura Rossi to organise 100 screenings of the film with live orchestral accompaniment for her newly composed score in the 100th anniversary year of the actual battle. With 51 screenings in 2016 and 29 in  2017 plus any we missed together with various overseas screenings it looks like Laura achieved her ambitious target. Phantom of the Opera, Nosferatu and The Lodger remain widely regarded popular classics so their high position is not surprising.

2017 plus any we missed together with various overseas screenings it looks like Laura achieved her ambitious target. Phantom of the Opera, Nosferatu and The Lodger remain widely regarded popular classics so their high position is not surprising.

Further down the list there were 11 screenings for Napoleon (Dir. Abel Gance, Fr, 1927), well down on last year’s heavily promoted 43 but still respectable. Perennial favourites Sherlock  Jr (Dir.Buster Keaton, US, 1924) and Sunrise : A Song Of Two Humans (Dir. F W Murnau, US, 1927) both had 10 screenings. Battleship Potemkin (Dir. Sergei Eisenstein, USSR, 1925) got nine as did Pandora’s Box (Dir. G W Pabst, Ger, 1929) helped by promotions for Pamela Hutchinson’s excellent new book on the film. Another Keaton classic, this time The Cameraman (Dir. Edward Sedgwick & Buster Keaton, US, 1928 ) got eight as did Soviet ‘western’ Down By Law (Dir . Lev Kuleshov, USSR, 1926 ) on tour with a new score by R M Hubbert. A Cottage on Dartmoor (Dir. Anthony Asquith, UK, 1929) got seven screenings, displacing Asquith’s other silent classic, Underground (Dir Anthony Asquith, UK, 1928) which was similarly well screened in 2016. Revolutionary classic The End of St Petersburg (Dir. Vsevolod Pudovkin, USSR, 1927) also got seven, on tour with a new score by Harmonieband.

Jr (Dir.Buster Keaton, US, 1924) and Sunrise : A Song Of Two Humans (Dir. F W Murnau, US, 1927) both had 10 screenings. Battleship Potemkin (Dir. Sergei Eisenstein, USSR, 1925) got nine as did Pandora’s Box (Dir. G W Pabst, Ger, 1929) helped by promotions for Pamela Hutchinson’s excellent new book on the film. Another Keaton classic, this time The Cameraman (Dir. Edward Sedgwick & Buster Keaton, US, 1928 ) got eight as did Soviet ‘western’ Down By Law (Dir . Lev Kuleshov, USSR, 1926 ) on tour with a new score by R M Hubbert. A Cottage on Dartmoor (Dir. Anthony Asquith, UK, 1929) got seven screenings, displacing Asquith’s other silent classic, Underground (Dir Anthony Asquith, UK, 1928) which was similarly well screened in 2016. Revolutionary classic The End of St Petersburg (Dir. Vsevolod Pudovkin, USSR, 1927) also got seven, on tour with a new score by Harmonieband.

Footnote: According to the London Symphony website there were 58 screenings in 2017 so we clearly missed quite a few but our review is based purely on the screenings we ourselves have listed during the year. Based on a total of 58 screenings London Symphony would be the second most frequently screened silent film of the year.

Screening venues

The number of screening venues in 2017 remained broadly similar to the previous year, with 281 compared to 263 in 2016. As well as cinemas, these venues included cathedrals, churches, church halls, town halls, community centres, public houses, schools, museums and castles. New venues in 2017 included a canal boat, a hotel, a shopping centre car park, a housing estate, a Hindu temple and a meditation centre. Oh, and in 2017 there were also three screenings in railway stations compared to just one the previous year!

The most significant venue development in 2017 was the inclusion of main stream cinema chains. Both the Vue and Picture House chains picked up screenings of Der Mude Tod and Metropolis. London Symphony was also significant in expanding the range of venues, often being screened in very non-traditional locales.

As with 2016, the most significant silent film venue was BFI Southbank, with 88 screenings, ten more than the previous year. Amongst the highlights they screened were stunning restorations of Monet Cristo (Dir. Henri  Fescourt, FR, 1929) and The Dumb Girl of Portici (Dir. Lois Weber, US, 1916), an introduction to Indian silent film, a beautiful and virtually unknown Austrian melodrama Little Veronica (Dir. Robert Land, Aust, 1929) and an early Italian neo-realist gem Rails (Dir. Mario Camerini, It, 1929). Yet while the number of silent films screened at BFI went up the range of titles screened actually went down, only 31 different films, compared to 35 the previous year. Did we really need 29 screenings of Der Mude Tod when the film was being widely screened at cinemas nation-wide. And there continues to be copious repetition of the best known films (Sunrise; A Song of Two

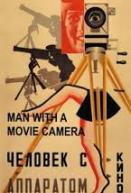

Fescourt, FR, 1929) and The Dumb Girl of Portici (Dir. Lois Weber, US, 1916), an introduction to Indian silent film, a beautiful and virtually unknown Austrian melodrama Little Veronica (Dir. Robert Land, Aust, 1929) and an early Italian neo-realist gem Rails (Dir. Mario Camerini, It, 1929). Yet while the number of silent films screened at BFI went up the range of titles screened actually went down, only 31 different films, compared to 35 the previous year. Did we really need 29 screenings of Der Mude Tod when the film was being widely screened at cinemas nation-wide. And there continues to be copious repetition of the best known films (Sunrise; A Song of Two  Humans (Dir. F W Murnau, US, 1927) played seven times, Pandoras’s Box (Dir. G W Pabst, Ger, 1929) five times, Man with a Movie Camera (Dir. Dziga Vertov, USSR, 1929)and Nosferatu (Dir. F W Murnau, Ger, 1922) three times each) seemingly used just as gap fillers on the programme and often not even with live accompaniment. The BFI’s lack of appreciation for silent film was summed up with their single screening last year of the little known but wonderful British comedy Not For Sale (Dir. W P Kellino, GB, 1924), hidden away in Screen 3, and to which so many people turned up that they ran out of programme notes! The message rang out loud and clear, if you put on more adventurous silent film programming, the people will come!

Humans (Dir. F W Murnau, US, 1927) played seven times, Pandoras’s Box (Dir. G W Pabst, Ger, 1929) five times, Man with a Movie Camera (Dir. Dziga Vertov, USSR, 1929)and Nosferatu (Dir. F W Murnau, Ger, 1922) three times each) seemingly used just as gap fillers on the programme and often not even with live accompaniment. The BFI’s lack of appreciation for silent film was summed up with their single screening last year of the little known but wonderful British comedy Not For Sale (Dir. W P Kellino, GB, 1924), hidden away in Screen 3, and to which so many people turned up that they ran out of programme notes! The message rang out loud and clear, if you put on more adventurous silent film programming, the people will come!

And talk of adventurous film programming leads naturally to the Kennington Bioscope at the still under threat Cinema Museum, whose 42 screenings keeps them in second spot numerically but streets ahead in content. Their 42 screenings not only comprised 42 different titles but virtually all the films shown were little known, rarely screened and often verging on the obscure (so obscure in fact, that at least one shown by KenBio this year, She’s a Sheik (Dir.  Clarence Badger, US, 1927), is widely believed to be lost!). And this year’s screenings certainly provided a treasure trove of delights, including three early gangster classics, The Musketeers of Pig Alley (Dir. D W Griffith, US, 1912), Regeneration (Dir. Raoul Walsh, US, 1915) and Underworld (Dir. Josef Von Sternberg, US, 1927), the part rural melodrama and part anthropological study Stark Love (Dir. Karl Brown, US, 1927), Dietrich classic The Woman Men Long For (Dir. Curtis Bernhardt, Ger, 1929)and the equally sublime

Clarence Badger, US, 1927), is widely believed to be lost!). And this year’s screenings certainly provided a treasure trove of delights, including three early gangster classics, The Musketeers of Pig Alley (Dir. D W Griffith, US, 1912), Regeneration (Dir. Raoul Walsh, US, 1915) and Underworld (Dir. Josef Von Sternberg, US, 1927), the part rural melodrama and part anthropological study Stark Love (Dir. Karl Brown, US, 1927), Dietrich classic The Woman Men Long For (Dir. Curtis Bernhardt, Ger, 1929)and the equally sublime  Pavement Butterfly ((Dir. Richard Eichberg, Ger/UK, 1929) with Anna May Wong as well as a chance to see another of the W W Jacobs/Manning-Haynes/Lydia Hayward classic comedies The Skipper’s Wooing (Dir. H Manning-Haynes, UK, 1922). Special mention must go also to Kevin Brownlow for allowing access to his peerless silent film collection which enables the KenBio to provide us with a never ending source of cinematic delights. Long may this continue. Particular thanks also to all of the accompanists there who give freely of their time and make it even more of a special event.

Pavement Butterfly ((Dir. Richard Eichberg, Ger/UK, 1929) with Anna May Wong as well as a chance to see another of the W W Jacobs/Manning-Haynes/Lydia Hayward classic comedies The Skipper’s Wooing (Dir. H Manning-Haynes, UK, 1922). Special mention must go also to Kevin Brownlow for allowing access to his peerless silent film collection which enables the KenBio to provide us with a never ending source of cinematic delights. Long may this continue. Particular thanks also to all of the accompanists there who give freely of their time and make it even more of a special event.

In equal third position this year was the Barbican and the Hippodrome, Bo’ness with 20 screenings each. The Barbican continues to screen an impressive range of European and Asian silent rarities with a diverse range of musical accompanists which this year included a stunning Czech melodrama Sins of Love (Dir. Karel Lamac, Cz, 1929) never previously shown in Britain, I Was Born But…(Dir.  Yasujiro Ozu, Jap, 1932) with live Benshi narration, the marathon eight hour version of Les Miserables (Dir. Henri Fescourt, Fr, 1925) with heroics from Neil Brand on piano and the truly stunning Shiraz ( (Dir. Franz Osten, Ind/Ger, 1928) with magnificent live score from sitarist and composer Anoushka Shankar. Most of the Hippodrome’s screenings focused upon their annual HippFest, particular highlights being The Patsy (Dir. King Vidor, US, 1928) with Marion Davies at her comedic best and superbly

Yasujiro Ozu, Jap, 1932) with live Benshi narration, the marathon eight hour version of Les Miserables (Dir. Henri Fescourt, Fr, 1925) with heroics from Neil Brand on piano and the truly stunning Shiraz ( (Dir. Franz Osten, Ind/Ger, 1928) with magnificent live score from sitarist and composer Anoushka Shankar. Most of the Hippodrome’s screenings focused upon their annual HippFest, particular highlights being The Patsy (Dir. King Vidor, US, 1928) with Marion Davies at her comedic best and superbly  accompanied by The Sprockets, The Goddess (Dir. Wu Yonggang, Chi, 1934) with John Sweeney on piano and The Informer (Dir. Arthur Robison, UK, 1929) accompanied by with Günter Buchwald & Stephen Horne.

accompanied by The Sprockets, The Goddess (Dir. Wu Yonggang, Chi, 1934) with John Sweeney on piano and The Informer (Dir. Arthur Robison, UK, 1929) accompanied by with Günter Buchwald & Stephen Horne.

The Phoenix Cinema in Leicester screened 17 silents, mainly for the British Silent Film Festival and it would have been better placed except for the fact that many of the films at this year’s festival reflected the festival theme of the transition to talkies so couldn’t really be included as silents. The Irish Film Institute in Dublin also screened 17, including a well programmed collection of films from Weimar Germany. The Watershed Bristol had 14 screenings, the Filmhouse Edinburgh had 12 and the Tyneside Cinema in Newcastle 11. London’s Regent Street Cinema and ICA both had ten screenings as did the Abbeydale Picturehouse in Sheffield while the Sands Cinema Club in London and the Hyde Park Picture House in Leeds each had nine silent screenings.

Film Highlights of 2017

January started with a series of classics at BFI, including The Lodger, Sunrise, Pandora’s Box and Piccadilly but then somewhat more ambitiously presented an evening of silent films selected by director Martin  Scorsese. The KenBio opened their year with classic Coleen Moore comedy Orchids and Ermine (Dir. Alfred Santell, US, 1927), a personal favourite. Bristol’s Slapstick Festival included some great knockabout comedies at the Watershed such as Paths To Paradise (Dir. Clarence Badger, US, 1925) with Raymond Griffith and Max Linder’s Seven Years Bad Luck (Dir. Max Linder, US, 1921) but was also interesting for a couple of more restrained European comedy-dramas, Thomas Graal’s Best Film (Dir. Maurice Stiller, Sw, 1918) and Master of the House (Dir. Carl Theodor Dryer, Sw, 1925). It also screened that perennial

Scorsese. The KenBio opened their year with classic Coleen Moore comedy Orchids and Ermine (Dir. Alfred Santell, US, 1927), a personal favourite. Bristol’s Slapstick Festival included some great knockabout comedies at the Watershed such as Paths To Paradise (Dir. Clarence Badger, US, 1925) with Raymond Griffith and Max Linder’s Seven Years Bad Luck (Dir. Max Linder, US, 1921) but was also interesting for a couple of more restrained European comedy-dramas, Thomas Graal’s Best Film (Dir. Maurice Stiller, Sw, 1918) and Master of the House (Dir. Carl Theodor Dryer, Sw, 1925). It also screened that perennial  Keaton-meets-Beckett oddity Film (Dir. Alan Schneider, US, 1966) and accompanying documentary NOT Film (Ross Lipman, US, 2015).

Keaton-meets-Beckett oddity Film (Dir. Alan Schneider, US, 1966) and accompanying documentary NOT Film (Ross Lipman, US, 2015).

February kicked off with the early ethnographic film Salt For Svanetia (Dir. Mikhail Kalatozov, USSR, 1930) and the gloriously restored Arabian Nights (aka One Thousand and One Nights) (Dir. Viktor Tourjansky, Fr, 1921) at the KenBio with accompaniment from guest US pianist Jeff Rapsis. The Soviet theme continued at the Barbican with A Sixth part of the  World (Dir. Dziga Vertov, USSR, 1926) accompanied superbly by John Sweeney. At Saffron Waldon Screen, there was a showing of Robin Hood (Dir. Allan Dwan, US, 1922) featuring full orchestral accompaniment with a new and blisteringly good score from Neil Brand.

World (Dir. Dziga Vertov, USSR, 1926) accompanied superbly by John Sweeney. At Saffron Waldon Screen, there was a showing of Robin Hood (Dir. Allan Dwan, US, 1922) featuring full orchestral accompaniment with a new and blisteringly good score from Neil Brand.

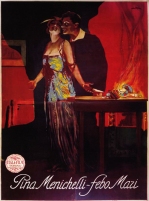

Returning to Bristol in March, there was a very rare screening of Italian diva masterpiece Il Fuoco (The Fire) (Dir Giovanni Pastrone, It, 1916) starring Pina Menichelli at the Cube.  Back in London, the KenBio hosted their first (and hopefully not last) Silent Western Saturday, with delights like Thundering Hoofs (Dir. Albert Rogell, US, 1924) and The Devil Horse (Dir. Fred Jackman, US, 1926), an introduction to the world of silent film cowgirls featuring the likes of Texas Guinan and culminating with the stunning Winning of Barbara Worth (Dir. Henry King, US, 1926). London’s Fashion on Film Festival saw welcome screenings of Russian science fiction epic Aelita (Dir. Yakov Protazanov, USSR, 1924) at the Genesis Cinema and the recently rediscovered Beyond The Rocks (Dir. Sam Wood, US, 1922) at the Rio Dalston, the only film in which Gloria Swanson and Rudolph Valentino appeared

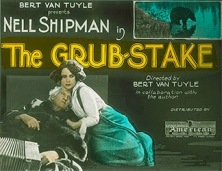

Back in London, the KenBio hosted their first (and hopefully not last) Silent Western Saturday, with delights like Thundering Hoofs (Dir. Albert Rogell, US, 1924) and The Devil Horse (Dir. Fred Jackman, US, 1926), an introduction to the world of silent film cowgirls featuring the likes of Texas Guinan and culminating with the stunning Winning of Barbara Worth (Dir. Henry King, US, 1926). London’s Fashion on Film Festival saw welcome screenings of Russian science fiction epic Aelita (Dir. Yakov Protazanov, USSR, 1924) at the Genesis Cinema and the recently rediscovered Beyond The Rocks (Dir. Sam Wood, US, 1922) at the Rio Dalston, the only film in which Gloria Swanson and Rudolph Valentino appeared  together. In Scotland HippFest highlights at the Bo’Ness Hippodrome included a rare screening of The Grub Stake (Dir. Bert vn Tuyle/Nell Shipman, US, 1923) with Nell Shipman, Soviet ‘western’ By The Law (Dir, Lev Kuleshov, USSR, 1926), Marion Davies delightful in The Patsy (Dir. King Vidor, US, 1928) and the recently restored silent version of The Informer (Dir. Arthur Robinson, UK, 1929). Back in London, the month ended with an extremely rare screening of the disturbing World

together. In Scotland HippFest highlights at the Bo’Ness Hippodrome included a rare screening of The Grub Stake (Dir. Bert vn Tuyle/Nell Shipman, US, 1923) with Nell Shipman, Soviet ‘western’ By The Law (Dir, Lev Kuleshov, USSR, 1926), Marion Davies delightful in The Patsy (Dir. King Vidor, US, 1928) and the recently restored silent version of The Informer (Dir. Arthur Robinson, UK, 1929). Back in London, the month ended with an extremely rare screening of the disturbing World  War 1 vengeance film Behind The Door (Dir. Irvin Willat, US, 1919) at the BFI.

War 1 vengeance film Behind The Door (Dir. Irvin Willat, US, 1919) at the BFI.

Moving on to April, there was a rare screening at London’s French Institute of Jean Renoir’s debut feature-length film, La Fille de l’eau (Dir. Jean Renoir,Fr 1924). Other rarities screened during the month included A Lowland Cinderella (aka A Highland Maid) (Dir. Sidney Morgan, 1921) at King’s College and Stark Love (Dir. Karl Brown, 1927) presented by the KenBio. But the month was dominated by two mammoth screenings. Firstly, at Birmingham’s John Lee Theatre there was a presentation over two days of French serial House of Mystery (Dir. Alexandre Volkoff, Fr, 1921-23), all 383  minutes. Secondly, the Barbican in London screened the 397 minute Les Miserables (Dir. Henri Fescourt, 1925 ) over one day with Neil Brand accompanying the entire film.

minutes. Secondly, the Barbican in London screened the 397 minute Les Miserables (Dir. Henri Fescourt, 1925 ) over one day with Neil Brand accompanying the entire film.

May was dominated by the second annual Yorkshire Silent Film Festival, a month long extravaganza involving well over 30 screenings across the county with a good mix of populist and less well known titles. Highlights this year included Soviet comedy classics Girl With A Hat Box (Dir. Boris Barnet, 1927) and The House on Trubnaya (Dir. Boris Barnett, 1928); Japanese crime melodrama Dragnet Girl (Dir. Yasujiro Ozu,  1933); the epic Ben Hur (Dir. Fred Niblo, 1925) and British thrillers Blackmail (Dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1929) and The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (Dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1927), all featuring live musical accompaniment. In the rest of the country there was a screening at the French Institute in Edinburgh of the somewhat style-over-substance classic L’Inhumaine (Dir. Marcel L’Herbier, 1924), the BFI took a fascinating look at silent Indian cinema while South West Silents were examining sin and silent cinema with a screening of exploitation silent The Devil’s Needle (Dir. Chester Withey, US, 1916) at the Lansdown Public House.

1933); the epic Ben Hur (Dir. Fred Niblo, 1925) and British thrillers Blackmail (Dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1929) and The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (Dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1927), all featuring live musical accompaniment. In the rest of the country there was a screening at the French Institute in Edinburgh of the somewhat style-over-substance classic L’Inhumaine (Dir. Marcel L’Herbier, 1924), the BFI took a fascinating look at silent Indian cinema while South West Silents were examining sin and silent cinema with a screening of exploitation silent The Devil’s Needle (Dir. Chester Withey, US, 1916) at the Lansdown Public House.

June opened with another mammoth Louis Frescourt film, the near four hour classic Monte Cristo (Dir. Louis Fescourt, Fr, 1929) at the BFI. The Soviet documentary In Spring (Dir. Mikhail Kaufman, Ukr/USSR, 1929) played at London’s Bertha Doc House and amply demonstrated how director Kaufman has long been unjustly overshadowed by his brother Dziga Vertov. June also saw the nationwide re-release of little known but superb early Lang film Der Müde Tod (Dir. Fritz Lange, 1921). We also had the eagerly anticipated second annual KenBio Silent Film Weekend,

June opened with another mammoth Louis Frescourt film, the near four hour classic Monte Cristo (Dir. Louis Fescourt, Fr, 1929) at the BFI. The Soviet documentary In Spring (Dir. Mikhail Kaufman, Ukr/USSR, 1929) played at London’s Bertha Doc House and amply demonstrated how director Kaufman has long been unjustly overshadowed by his brother Dziga Vertov. June also saw the nationwide re-release of little known but superb early Lang film Der Müde Tod (Dir. Fritz Lange, 1921). We also had the eagerly anticipated second annual KenBio Silent Film Weekend,  highlights of which included the stunning documentary Grass: A Nation’s Battle For Life (Dir. Merian C. Cooper/Ernest B. Schoedsack, US, 1925), Dietrich in The Woman One Longs For (Dir, Curtis Bernhard, Ger, 1929), another delightful British comedy The Skipper’s Wooing (Dir. H Manning-Haynes, GB, 1922) and the truly bizarre The Unholy Three (Dir. Tod Browning, US, 1925). Elsewhere, Metropolis (Dir. Fritz Lange, 1927) got a rare outing on the BFI IMAX’s mammoth screen, we got a lesson in How To Become A Benshi at Foyle’s bookshop and there was a re-enactment of A Night At The Cinema In 1914 at Edinburgh’s Festival Theatre.

highlights of which included the stunning documentary Grass: A Nation’s Battle For Life (Dir. Merian C. Cooper/Ernest B. Schoedsack, US, 1925), Dietrich in The Woman One Longs For (Dir, Curtis Bernhard, Ger, 1929), another delightful British comedy The Skipper’s Wooing (Dir. H Manning-Haynes, GB, 1922) and the truly bizarre The Unholy Three (Dir. Tod Browning, US, 1925). Elsewhere, Metropolis (Dir. Fritz Lange, 1927) got a rare outing on the BFI IMAX’s mammoth screen, we got a lesson in How To Become A Benshi at Foyle’s bookshop and there was a re-enactment of A Night At The Cinema In 1914 at Edinburgh’s Festival Theatre.

Beginning in London, July saw the BFI really came good with Rails (aka Rotaie)(Dir. Mario Camerini, It, 1928) a remarkable but virtually unknown early Italian neo-realist drama. The BFI also twice screened Greed (Dir. Erich Von Stroheim, US, 1924), Stroheim’s flawed masterpiece.  Persephone Bookshop screened The Home Maker (Dir. King Baggot, US, 1925) a virtually unknown but intriguing film about domestic role reversal between the sexes while at the KenBio, Kevin Brownlow brought along some more of his 9.5mm films for an entertaining evening. Outside London, Bristol’s Cinema Rediscovered Festival included some early colour silents, a trip through India and a rare showing for the fascinating documentary Dawson City – Frozen Time (Dir. Bill Morrison, US, 2016) all at the Watershed.

Persephone Bookshop screened The Home Maker (Dir. King Baggot, US, 1925) a virtually unknown but intriguing film about domestic role reversal between the sexes while at the KenBio, Kevin Brownlow brought along some more of his 9.5mm films for an entertaining evening. Outside London, Bristol’s Cinema Rediscovered Festival included some early colour silents, a trip through India and a rare showing for the fascinating documentary Dawson City – Frozen Time (Dir. Bill Morrison, US, 2016) all at the Watershed.

In August, Dublin’s IFI began a short season of the films of the Weimar Republic, including such gems as Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (Dir. Walter Ruttman, Ger, 1927), Woman  In The Moon (Dir. Fritz Lang, Ger, 1929), Faust (Dir. F W Murnau, Ger, 1926) and The Mountain Lion (Dir. Ernst Lubitsch, Ger, 1921). The documentary Drifters (Dir. John Griersen, UK, 1929), about the North Sea herring industry, was screened at a number of the same East Coast ports previously involved in the herring trade. In an intriguing experiment, each screening was accompanied by musicians local to that area and included other contemporary historical footage also unique to that location. The historic Wilton’s Music Hall in London put on a short series of silents including Epic of Everest (Dir. J B L Noel, UK,

In The Moon (Dir. Fritz Lang, Ger, 1929), Faust (Dir. F W Murnau, Ger, 1926) and The Mountain Lion (Dir. Ernst Lubitsch, Ger, 1921). The documentary Drifters (Dir. John Griersen, UK, 1929), about the North Sea herring industry, was screened at a number of the same East Coast ports previously involved in the herring trade. In an intriguing experiment, each screening was accompanied by musicians local to that area and included other contemporary historical footage also unique to that location. The historic Wilton’s Music Hall in London put on a short series of silents including Epic of Everest (Dir. J B L Noel, UK,  1924), Shooting Stars (Dir. Anthony Asquith and A.V. Bramble, UK, 1928) and The Lost World (Dir. Harry Hoyt, US, 1925) all with live musical accompaniment from The Lucky Dog Picture House.

1924), Shooting Stars (Dir. Anthony Asquith and A.V. Bramble, UK, 1928) and The Lost World (Dir. Harry Hoyt, US, 1925) all with live musical accompaniment from The Lucky Dog Picture House.

September saw the first of numerous screenings of London Symphony (Dir. Alex Barrett, UK, 2017) a brand new silent film , a city symphony , offering a poetic journey through London. But the month was pretty much dominated by the British Silent Film Festival, held in Leicester’s Phoenix Cinema. Although the festival’s central theme of ‘Transition to Sound’ meant there were a good few ‘talkies’, the silent highlights included Cocktails (Dir. Monty Banks, UK, 1928) featuring Dutch comedy duo Pat and  Patachon, Different from the Others (Dir. Richard Oswald, Ger, 1919) an early sympathetic treatment of gay rights, knock-about comedy Hands Up (Dir. Clarence Badger, US, 1926) featuring Raymond Griffith, Swedish comedy (!) A Sister of Six (Dir. Ragnar Hylten-Cavallius, Ger/Swe/UK. 1926) starring the UK’s own Betty Balfour and the lyrical and the beautiful L’Hirondelle et la Mésange (Dir. Andre Antoine, Fr, 1920) with knockout accompaniment from Stephen Horne and Elizabeth Jane Baldry. The KenBio fielded another gem with Filibus (Dir. Mario Roncoroni, It, 1915), a story about a

Patachon, Different from the Others (Dir. Richard Oswald, Ger, 1919) an early sympathetic treatment of gay rights, knock-about comedy Hands Up (Dir. Clarence Badger, US, 1926) featuring Raymond Griffith, Swedish comedy (!) A Sister of Six (Dir. Ragnar Hylten-Cavallius, Ger/Swe/UK. 1926) starring the UK’s own Betty Balfour and the lyrical and the beautiful L’Hirondelle et la Mésange (Dir. Andre Antoine, Fr, 1920) with knockout accompaniment from Stephen Horne and Elizabeth Jane Baldry. The KenBio fielded another gem with Filibus (Dir. Mario Roncoroni, It, 1915), a story about a  female cross dressing master criminal who lives in an airship. What was there about that not to like! The BFI also came good with a rare chance to see Not For Sale (Dir. W P Kellino, UK, 1924) one of the most charming British silent comedies ever made. There was also another chance to catch a Japanese silent with live Benshi narration with A Page of Madness (Dir.Teinosuke Kinugasa, Jap, 1926) at London’s King’s College.

female cross dressing master criminal who lives in an airship. What was there about that not to like! The BFI also came good with a rare chance to see Not For Sale (Dir. W P Kellino, UK, 1924) one of the most charming British silent comedies ever made. There was also another chance to catch a Japanese silent with live Benshi narration with A Page of Madness (Dir.Teinosuke Kinugasa, Jap, 1926) at London’s King’s College.

In October, it was the turn of Metropolis (Dir. Fritz Lang, Ger, 1927) to get the nationwide re-release treatment. There was the first of several screenings of By the Law (Po Zakonu) as musician, singer and song-writer R.M. Hubbert took the film on tour with his new score. The 2017 London Film Festival included a number of superb silents in its programme. Both The Dumb Girl of Portici (Dir. Lois Weber, US, US, 1915) and Little Veronika (Dir. Robert Land, Aust-Ger, 1930) at the BFI were marvelous but the festival’s knock-out silent had to be Shiraz (Dir. Franz Osten, 1928) with live accompaniment from Indian composer and  sitar player Anoushka Shankar and her ensemble, playing to a rapturous audience of almost 2000 at the Barbican. And amongst a clutch of films marking Haloween, Haxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages (Dir. Benjamin Christensen, Swe., 1922) with live translation of the Swedish inter-titles by Reece Shearsmith and musical accompaniment from Stephen Horne got rave reviews. On a more worrying note we also got first word of the imminent threat to the future of the Cinema Museum, a much loved institution and home to the KenBio, with the site’s owners refusing to sell to the museum, apparently

sitar player Anoushka Shankar and her ensemble, playing to a rapturous audience of almost 2000 at the Barbican. And amongst a clutch of films marking Haloween, Haxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages (Dir. Benjamin Christensen, Swe., 1922) with live translation of the Swedish inter-titles by Reece Shearsmith and musical accompaniment from Stephen Horne got rave reviews. On a more worrying note we also got first word of the imminent threat to the future of the Cinema Museum, a much loved institution and home to the KenBio, with the site’s owners refusing to sell to the museum, apparently  preferring instead to sell the land to the highst bidder for re-development. The museum, its friends and supporters are campaigning valiantly to save it but it is still far from secure.

preferring instead to sell the land to the highst bidder for re-development. The museum, its friends and supporters are campaigning valiantly to save it but it is still far from secure.

There was a rare visit of silent film to Orkney in November with two screenings of A Cottage on Dartmoor (Dir. Anthony Asquith, 1929) accompanied by Stephen Horne while at Eden Court in Inverness, their film festival included The Woman He Scorned (Dir. Paul Czinner, UK, 1929) with Pola Negri, the enthralling documentary Dawson City – Frozen Time (Dir. Bill Morrison, US, 2016) and another chance to catch film historian Geoff Brown’s hugely entertaining illustrated talk, The Last Silent Picture Show (“Oh Tondelayo, Tondelayo”!!!). Then there was the KenBio’s third festival of the year, a Silent Comedy Saturday, highlights of which included Innocent Husbands (Dir. Leo McCarey, US, 1925) with Charley Chase, Max Linder in Max Wants A Divorce (Dir. Max Linder, US, 1917) and Harold Lloyd as The Kid Brother (Dir. Ted Wilde, US. 1927).The ICA in London featured a series of classic Dovzhenko films including Zvenyhora (Dir. Oleksandr Dovzhenko, USSR 1927), Arsenal (Dir. Oleksandr Dovzhenko, USSR 1928) and Earth (Dir. Oleksandr Dovzhenko, USSR 1930) while the Barbican screened another little known East European masterpiece Sins Of Love (Dir. Karel Lamac, Czech, 1929). Late in the month, London’s Close-

Innocent Husbands (Dir. Leo McCarey, US, 1925) with Charley Chase, Max Linder in Max Wants A Divorce (Dir. Max Linder, US, 1917) and Harold Lloyd as The Kid Brother (Dir. Ted Wilde, US. 1927).The ICA in London featured a series of classic Dovzhenko films including Zvenyhora (Dir. Oleksandr Dovzhenko, USSR 1927), Arsenal (Dir. Oleksandr Dovzhenko, USSR 1928) and Earth (Dir. Oleksandr Dovzhenko, USSR 1930) while the Barbican screened another little known East European masterpiece Sins Of Love (Dir. Karel Lamac, Czech, 1929). Late in the month, London’s Close- Up Cinema showed two classics of Italian diva-cinema, Assunta Spina (Dir. Gustavo Serena and Francesca Bertini, It, 1915) starring Francesca Bertini and Ma l’Amor Mio Non Muore ( Dir. Mario Casarini, It, 1913)with Lyda Borelli.

Up Cinema showed two classics of Italian diva-cinema, Assunta Spina (Dir. Gustavo Serena and Francesca Bertini, It, 1915) starring Francesca Bertini and Ma l’Amor Mio Non Muore ( Dir. Mario Casarini, It, 1913)with Lyda Borelli.

Finally, in December the KenBio had some classic Anna May Wong in Pavement Butterfly (Dir. Richard Eichberg, Ger/UK, 1929) as well as a very funny Bebe Daniels in She’s a Sheik (Dir. Clarence Badger, US, 1927), a film widely regarded as lost but clearly not in the opinion of Kevin Brownlow who supplied this print. It was then the turn of the BFI to put on an Italian dive classic, this time Rapsodia Satanica (Dir. Nino Oxilia, It, 1917) again starring Lyda Borelli. There was also a screening of The General (Dir. Buster Keaton/Clyde Bruckman, 1926) with live accompaniment from Lillian Henley at the Palace Cinema in Broadstairs which, while perhaps not a seminal event in itself, marks the first in a regular series of silent screenings with live music planned at this venue which has got to be a positive end-of-year step in helping to spread the popularity of silent film with live accompaniment across the country.

Pavement Butterfly (Dir. Richard Eichberg, Ger/UK, 1929) as well as a very funny Bebe Daniels in She’s a Sheik (Dir. Clarence Badger, US, 1927), a film widely regarded as lost but clearly not in the opinion of Kevin Brownlow who supplied this print. It was then the turn of the BFI to put on an Italian dive classic, this time Rapsodia Satanica (Dir. Nino Oxilia, It, 1917) again starring Lyda Borelli. There was also a screening of The General (Dir. Buster Keaton/Clyde Bruckman, 1926) with live accompaniment from Lillian Henley at the Palace Cinema in Broadstairs which, while perhaps not a seminal event in itself, marks the first in a regular series of silent screenings with live music planned at this venue which has got to be a positive end-of-year step in helping to spread the popularity of silent film with live accompaniment across the country.

Our Top Ten Of The Year

Out of the 118 silent film screenings we managed to get to over the past year it is now time to pick out our top ten. As we emphasised last year, this is not intended to be a judgement of the ‘best’ films, whatever that means, just the ten most enjoyable silent events we have been to and in particular those which left us with that ‘wow’ feeling when the music stopped and house lights came back on.

But the problem is that the more films we see the harder it becomes to pick out our ten favourites. So this year we have to resort to a little cheating. Two events which would have made our top ten were not really silent films per se so these we can mention separately.

The first was an illustrated presentation given by US academic Paul Pickowicz, on Women in Chinese Silent Cinema at this year’s HippFest. Having travelled to China in the 1980s to interview surviving film stars and technicians (much in the way that Kevin Brownlow went to US for the same reason) his subject knowledge was unrivaled and his enthusiasm shone through which made for a hugely informative presentation punctuated  by some fascinating and rare film clips. It was just a shame that the session was so poorly attended.

by some fascinating and rare film clips. It was just a shame that the session was so poorly attended.

Our second ‘cheat’ is Dawson City – Frozen Time (Dir. Bill Morrison, US, 2016) an almost flawless documentary on the discovery of hundreds of silent films, frozen in ice for decades in a disused swimming pool in Northern Canada. The story is beautifully told and covers not just the films themselves but also the rise (and fall) of Dawson City, its gold rush, the early movie business and even the development of nitrate film stock in an absolutely gripping fashion. The documentary is also brilliant in its use of clips from the rediscovered films (sadly often badly damaged) to cleverly illustrate aspects of the story. A fascinating and wonderfully entertaining documentary.

But now its time to pick out those ten favourite silent film screenings of the year. They are, in screening date order;

The Patsy (Dir. King Vidor, US, 1928) – 24th March at the Hippodrome Cinema, Bo’Ness with live accompaniment by The Sprockets. Marion Davies was at her best in comedy roles and this is one of her best with many a laugh out loud moment. She also displays a rare skill for impersonations, including a particularly faithful take-off of Lillian Gish. The film was beautifully accompanied by a jaunty score from Dutch film orchestra The Sprockets.

The Patsy (Dir. King Vidor, US, 1928) – 24th March at the Hippodrome Cinema, Bo’Ness with live accompaniment by The Sprockets. Marion Davies was at her best in comedy roles and this is one of her best with many a laugh out loud moment. She also displays a rare skill for impersonations, including a particularly faithful take-off of Lillian Gish. The film was beautifully accompanied by a jaunty score from Dutch film orchestra The Sprockets.

Monte Cristo (Dir. Henri Fescourt, Fr, 1929) – 4th June at BFI Southbank with live piano accompaniment from Costas Fotopoulos. It would have been nice to be able to include the other Fescourt film screened this yea, Les Miserables, but on balance this one just edged it. A sprawling tale, part adventure film, part taut melodrama it is filmed on a grand scale, with fantastic camera work and superb acting. Costas Fotopoulos’ four hour piano accompaniment was a triumph both in

Monte Cristo (Dir. Henri Fescourt, Fr, 1929) – 4th June at BFI Southbank with live piano accompaniment from Costas Fotopoulos. It would have been nice to be able to include the other Fescourt film screened this yea, Les Miserables, but on balance this one just edged it. A sprawling tale, part adventure film, part taut melodrama it is filmed on a grand scale, with fantastic camera work and superb acting. Costas Fotopoulos’ four hour piano accompaniment was a triumph both in  skill and endurance.

skill and endurance.

Rails (aka Rotaie) (Dir. Mario Camerini, It, 1929) – 23rd July at BFI Southbank with live musical accompaniment by Stephen Horne. This is an almost unknown but wonderful early example of Italian neo-realist cinema. With an upfront plot-line that anticipates the theme of Indecent Proposal (Dir. Adrian Lyne, US, 1999) Rails carries with it much deeper themes, the traversing of borders between poverty and wealth,between social classes and between indolence and meaningful work. The two leads (Kathe von Nagy and Maurizio D’Ancora) are both excellent and the film is beautifully shot. Stephen Horne’s accompaniment had a beautiful lightness of touch during the more intimate moments, while his discordant hand strumming of the piano wires  was the perfect match to the frenzy of the the roulette wheel scenes in which the couple’s world seemingly collapses.

was the perfect match to the frenzy of the the roulette wheel scenes in which the couple’s world seemingly collapses.

Sister of Six (aka Flickorna Gyurkovics) (Dir. Ragnar Hylten-Cavallius, Ger/Swe/UK. 1926) – 16th September at the Phoenix Cinema, Leicester with live piano accompaniment by Neil Brand. A romantic comedy starring our own Betty Balfour, with a wildly complex plot featuring layer upon layer of concealed identity, false identity and mistaken identity (not to mention some hilarious cross-dressing) as the lead players all struggle to find their preferred romantic partners. That so convoluted a plot can be successfully achieved in a silent film, with just a few inter-titles to move the story forward is a work of genius . But it all works beautifully and builds to an hilarious climax. Neil Brand on piano coped wonderfully with the often frenetic pace of the film.

L’Hirondelle et la Mésange (aka The Swallow and the Titmouse) (Dir. Andre Antoine, Fr, 1920) – 17th September at the Phoenix Cinema, Leicester with live musical accompaniment by Stephen Horne and Elizabeth Jane Baldry. Shot in 1920 but only edited and released in the 1983 this was the most exquisitely beautiful and serene film, a drama set on the canals in war-damaged northern France. But good as the film was, enjoyment of it was hugely enhanced by the gorgeous musical accompaniment from Stephen Horne (piano, flute and accordion) and Elizabeth-Jane Baldry (harp) performing a semi-improvised score. Together they caught perfectly the dream like pacing of the  film but then very effectively helped to underline the rising tensions and added marvellously to the shock of the dramatic climax. A sheer joy both to the eye and the ear.

film but then very effectively helped to underline the rising tensions and added marvellously to the shock of the dramatic climax. A sheer joy both to the eye and the ear.

Filibus (Dir. Mario Roncoroni, It, 1915) – 20th September at the Kennington Bioscope/Cinema Museum with live piano accompaniment from John Sweeney. Following the exploits of a female cross dressing master criminal who resides in an airship, this film was hugely inventive and great fun to watch. While the special effects, particularly of the airship, may seem crude in today’s era of seamless CGI, for their time they must have been hugely impressive.The film also exudes a subversive, anti-authoritarian streak and not so much challenges as absolutely demolishes established gender issues including a very early cinematic flirtation with lesbianism. An excellent piano accompaniment from John Sweeney  succeeded admirably in ramping up the suspense and excitement of the film, leaving the audience almost breathless at times

succeeded admirably in ramping up the suspense and excitement of the film, leaving the audience almost breathless at times

The Dumb Girl of Portici (Dir. Lois Weber, US, 1916) – 8th October at BFI Southbank with live musical accompaniment by Stephen Horne. Set in 17th century Naples at the time of an oppressive Spanish occupation, directed by Weber who, at that time, was a film maker comparable in both ability and status with the likes of Griffith and de Mille, the film also marked the only screen appearance by world renowned ballet dancer and choreographer Anna Pavlova. Notable for its superb sets, sumptuous costumes and beautifully choreographed and filmed dance scenes this is a true epic particularly as presented in this beautifully restored and tinted version. Stephen Horne on piano and flute as usual captured perfectly both the intimacy and excitement of the film.

Little Veronika (aka Die Kleine Veronika also known as Innocence/Unschuld) (Dir. Robert Land, Aus, 1929) – 10th October at BFI Southbank with live piano accompaniment by John Sweeney. A somewhat simple story of a loss of innocence as the young Veronica is cynically seduced by a much older man who then abandons her which the now almost forgotten director Land tackles without any trace of sensationalism and in doing so produces a film of delicate beauty. Lead Kath von Nagy again puts in a stunning performance and some of the location shooting is breathtaking. John Sweeney on piano matched the film beautifully, catching Veronika’s carefree naivety in the first half and then subtly emphasising her shock and dejection as events unfold.

Little Veronika (aka Die Kleine Veronika also known as Innocence/Unschuld) (Dir. Robert Land, Aus, 1929) – 10th October at BFI Southbank with live piano accompaniment by John Sweeney. A somewhat simple story of a loss of innocence as the young Veronica is cynically seduced by a much older man who then abandons her which the now almost forgotten director Land tackles without any trace of sensationalism and in doing so produces a film of delicate beauty. Lead Kath von Nagy again puts in a stunning performance and some of the location shooting is breathtaking. John Sweeney on piano matched the film beautifully, catching Veronika’s carefree naivety in the first half and then subtly emphasising her shock and dejection as events unfold.

Shiraz: A Romance of India (Dir. Franz Osten, Ger/Ind/UK, 1928) –  14th October at the Barbican, London with live musical accompaniment by sitarist and composer Anoushka Shankar and her ensemble. This, the London Film Festival’s Archive Gala, was a special night with a near capacity 2000 audience to see this beautifully restored film, an epic spectacle of love and loss in 17th century India with a (somewhat fictionalised) account of the life of the Princess who inspired the construction of the Taj Mahala. Filmed on a grand scale but with a a beautifully composed and structured story this was a film it was difficult to find fault with. Added to that, the accompaniment from Anoushka Shankar and her

14th October at the Barbican, London with live musical accompaniment by sitarist and composer Anoushka Shankar and her ensemble. This, the London Film Festival’s Archive Gala, was a special night with a near capacity 2000 audience to see this beautifully restored film, an epic spectacle of love and loss in 17th century India with a (somewhat fictionalised) account of the life of the Princess who inspired the construction of the Taj Mahala. Filmed on a grand scale but with a a beautifully composed and structured story this was a film it was difficult to find fault with. Added to that, the accompaniment from Anoushka Shankar and her  ensemble was out of this world, beautifully picking out the detail of the more intimate moments, but with a power and force behind the more grandiose scenes.

ensemble was out of this world, beautifully picking out the detail of the more intimate moments, but with a power and force behind the more grandiose scenes.

Sins of Love ( aka Hríchy Lásky, also known as Sin of a Beautiful Woman and The Last Mask) (Dir. Karel Lamac, Cz, 1929) – 19th November at the Barbican, London with live musical accompaniment by Ivan Acher. It really is difficult to think of a better silent film drama than Sins of Love. Everything about the film was just so close to perfection, the story, the direction, characterisation of the players, the acting, cinematography, it was just so hard to find fault with any aspect of its production. At the film’s conclusion there was an almost stunned silence as the excellence of what we had just watched sank in, almost a reluctance to break the spell in order to applaud Ivan Acher for his often ethereal, almost other-worldly, but wholly captivating accompaniment.

And that was it, another year of silent film listing and watching in a nutshell. As silentfilmcalendar.org moves into its third year its nice to be able to say that we are listing (and watching!) more silent films than ever before. If forced to pick just one highlight of the last year we would fail, because there were two events, at contrasting ends of the silent film spectrum, which we really just could not separate. At the grandiose, spectacular end there was  Shiraz: A Romance of India , an epic film, made on an epic scale with a fabulous and thunderous new score from Anoushka Shankar, playing to an audience of nigh-on 2000 people in the Barbican’s grand hall. At the other

Shiraz: A Romance of India , an epic film, made on an epic scale with a fabulous and thunderous new score from Anoushka Shankar, playing to an audience of nigh-on 2000 people in the Barbican’s grand hall. At the other  end of the scale was the gentle, intimate almost dream-like Hirondelle et la Mésange perfectly complemented by the subtle, under-stated playing of Stephen Horne and Elizabeth-Jane Baldry performing to perhaps a hundred people at the Phoenix, Leicester. Both events will live long in the memory and together they perfectly highlight everything we so love about silent cinema. And is there anything we regretted over the year? Well, there were all of those films we didn’t see! We failed miserably to make it up to Yorkshire this year for any of their silent festival and in particular how could we have missed Dragnet Girl (Dir. Yasujiro Ozu, 1933), a Japanese gangster film-noir with live harp accompaniment. Now that is a big regret but hopefully one that can be put right at a future date if someone cares to arrange another screening!

end of the scale was the gentle, intimate almost dream-like Hirondelle et la Mésange perfectly complemented by the subtle, under-stated playing of Stephen Horne and Elizabeth-Jane Baldry performing to perhaps a hundred people at the Phoenix, Leicester. Both events will live long in the memory and together they perfectly highlight everything we so love about silent cinema. And is there anything we regretted over the year? Well, there were all of those films we didn’t see! We failed miserably to make it up to Yorkshire this year for any of their silent festival and in particular how could we have missed Dragnet Girl (Dir. Yasujiro Ozu, 1933), a Japanese gangster film-noir with live harp accompaniment. Now that is a big regret but hopefully one that can be put right at a future date if someone cares to arrange another screening!

Finally, just to reiterate what we said last year, a big thank you to all of those people out there who give so generously of their time, energies and skills to make these silent events happen. Your efforts really are appreciated.