Having enjoyed another bumper year of silent film delights its now time to take our annual look back over the last 12 months to highlight a few trends, pick out some of the highs (and lows!) and come up with our favourite silent film events of the year.

Film Listings

The first surprise to emerge from an analysis of our film listings for 2019 is the low overall number of silent films screened during the year, just 473 films compared to 735 last year, 714 in 2017 and 548 in 2016. Whilst we do our best to include every silent film screening in the listings we don’t claim to be all inclusive as there are some which we inevitably miss. We have previously estimated that we catch about 80% of screenings, so it is possible this year that the lower overall figure means we have been much less successful in our listings efforts. However, this is considered unlikely. In fact, the number of cold contacts we receive from film programmers requesting we add their events to the listings means, if anything, we are probably becoming more successful.

The first surprise to emerge from an analysis of our film listings for 2019 is the low overall number of silent films screened during the year, just 473 films compared to 735 last year, 714 in 2017 and 548 in 2016. Whilst we do our best to include every silent film screening in the listings we don’t claim to be all inclusive as there are some which we inevitably miss. We have previously estimated that we catch about 80% of screenings, so it is possible this year that the lower overall figure means we have been much less successful in our listings efforts. However, this is considered unlikely. In fact, the number of cold contacts we receive from film programmers requesting we add their events to the listings means, if anything, we are probably becoming more successful.

A far more likely factor in explaining the downturn in silent screenings this year was the lack of any cinematic re-release for a silent film. In 2016 Napoleon (1927) was re-released (43 screenings) and there were multiple screenings (51 times) of Battle of the Somme (1916) to mark the hundredth anniversary of the battle. In 2017 there were re-releases of Der Mude Tod (1921, with 80 screenings) and Metropolis (1927, with 52 screenings). A modern silent, London Symphony (2017) was also heavily promoted that year, with 34 screenings. Last year, screenings were dominated by re-releases of both Pandora’s Box (1929, 122 screenings) and Shiraz (1928, 65 screenings). The release of another modern silent, Arcadia (2018) also got a further 20 screenings.

If we deduct these figures from the overall annual totals, then we are left with 454 screenings in 2016, 538 in 2017 and 528 in 2018 which compares much more favourably with this year’s overall figure of 473, indicating an improvement over the 2016 total and just a marginal (c.10%) decline on the previous two years.

While the total number of films screened may have fallen in comparison to previous years, it was also encouraging to note that the overall number of different films screened had held up last year at 259, compared to 262 in 2018 and 259 again in 2017.

Looking at individual film titles, the most frequently shown film in 2019 was Nosferatu (1922) with 21 screenings. Next up was The General (1926) with 14 screenings, followed by Phantom of the Opera (1925) with 12. The Golem (1920) and The Lodger (1927) shared the next slot with nine screenings each

Looking at individual film titles, the most frequently shown film in 2019 was Nosferatu (1922) with 21 screenings. Next up was The General (1926) with 14 screenings, followed by Phantom of the Opera (1925) with 12. The Golem (1920) and The Lodger (1927) shared the next slot with nine screenings each  while Metropolis (1927) had six. Rob Roy (1922), a Marvellous Mabel Normand compilation, Steamboat Bill Jr (1928), Assunta Spina (1915), Speedy (1928), Wonders of Creation (1925) and Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927) all followed with five screenings each.

while Metropolis (1927) had six. Rob Roy (1922), a Marvellous Mabel Normand compilation, Steamboat Bill Jr (1928), Assunta Spina (1915), Speedy (1928), Wonders of Creation (1925) and Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927) all followed with five screenings each.

It was no surprise to see perennial favourites such as Nosferatu, Phantom, The General and Metropolis topping the list of most frequently shown. The inclusion of The Golem is probably a result of a new, high quality restoration becoming available. But it was nice to see much less well known films such as Rob Roy, Assunta Spina and Wonders of Creation getting some frequent outings, all three the result of short tours around Scotland. Amongst individual stars, Buster Keaton of course continues to dominate, with two films in this list of the most frequently screened, further underlining his position as king of the silent comedians.

Screening Venues

As well as a decline in total number of films screened, there was also a significant fall this year in the number of different venues for silent film screenings, down to 175, compared to 238 in 2018 and 281 in 2017. In part, this can be accounted for by the absence of many first-run cinemas, reflecting the lack this year of a silent film cinematic re-release. But as usual, there are a few more novel venues to add to the list of silent film venues including a record store, a county records office, a lighthouse, a national park and a large hole in the ground (about which more later!)

The most significant silent film screening venue remains London’s BFI Southbank, a position it has held since our  listings began. This year they had 87 silent screenings, significantly lower than last year’s 145 although that figure did include over 80 screenings of just three films (Pandora’s Box, Shiraz and Arcadia). The key BFI highlight this year was a two month retrospective of films from the Weimar era, including a good selection of rarely screened gems ( eg Heaven on Earth (1927), Madame Dubarry (1919), Chronicles Of The Grey House (1925) and The Student of Prague (1926) etc) as well as the more regularly screened titles (Nosferatu, Variety, Caligari etc). Also of interest was the BFI’s Victorian Film Weekend with some beautifully restored treasures. It was just a pity that it overlapped with the Weimar festival, making for a hugely congested May/June when a camp bed at the back of screen one sometimes seemed like a necessity! But sadly by the end of the year the BFI was back to its traditional silent film quota of just one screening per month.

listings began. This year they had 87 silent screenings, significantly lower than last year’s 145 although that figure did include over 80 screenings of just three films (Pandora’s Box, Shiraz and Arcadia). The key BFI highlight this year was a two month retrospective of films from the Weimar era, including a good selection of rarely screened gems ( eg Heaven on Earth (1927), Madame Dubarry (1919), Chronicles Of The Grey House (1925) and The Student of Prague (1926) etc) as well as the more regularly screened titles (Nosferatu, Variety, Caligari etc). Also of interest was the BFI’s Victorian Film Weekend with some beautifully restored treasures. It was just a pity that it overlapped with the Weimar festival, making for a hugely congested May/June when a camp bed at the back of screen one sometimes seemed like a necessity! But sadly by the end of the year the BFI was back to its traditional silent film quota of just one screening per month.

The second most frequent venue remains Lambeth’s Cinema Museum, home to the Kennington Bioscope. The year’s 50 screenings may have been a slight decline on last year’s 58 but still included a Silent Comedy Weekend, a Silent Film Weekend and a Cecil B deMille Day as well as their regular Wednesday evening slots, all with top notch musical accompaniment. And as ever, their quality programming is invariably packed with rarely screened and long lost delights, all introduced by knowledgeable experts. Highlights this year included frenetic Czech comedy Lovers of an Old Criminal(1927), German melodrama Hungarian Rhapsody (1928), the incredible expressionist imagery of The Stone Rider (1923) and a shattering early social melodrama Ingeborg Holm (1914).

The second most frequent venue remains Lambeth’s Cinema Museum, home to the Kennington Bioscope. The year’s 50 screenings may have been a slight decline on last year’s 58 but still included a Silent Comedy Weekend, a Silent Film Weekend and a Cecil B deMille Day as well as their regular Wednesday evening slots, all with top notch musical accompaniment. And as ever, their quality programming is invariably packed with rarely screened and long lost delights, all introduced by knowledgeable experts. Highlights this year included frenetic Czech comedy Lovers of an Old Criminal(1927), German melodrama Hungarian Rhapsody (1928), the incredible expressionist imagery of The Stone Rider (1923) and a shattering early social melodrama Ingeborg Holm (1914).

Amongst other frequent venues, next came Bristol’s Watershed with 24 screenings, largely accounted for by Slapstick Festival presentations but with a nice Sunday afternoon Weimar season later in the year. The Hippodrome in Bo’ness was close behind with 23 screenings, mainly HippFest related but they too put on a small programme of silents during the Autumn. The Phoenix in Leicester came in with 21 screenings, mainly during its hosting of this year’s British Silent Film Festival.

Further down the list came the Barbican in London and the Cube in Bristol with eight screenings each. The Palace Broadstairs and Wilton’s Music Hall both had seven screenings. London’s Close-Up cinema had six while the Regent Street Cinema and Brunel Museum both had five. With four screenings each were Bristol Cathedral, Queen’s College Cambridge, the Forum Hexam, Square Chapel Halifax, Eden Court Inverness, the Lansdown Public House Bristol and the Musical Museum Brentford.

Amongst frequent venues its nice to see the Palace Broadstairs now established as a regular, with resident pianist Lillian Henley. The Brunel Museum in Rotherhithe has also become established, films being screened in the access shaft to Brunel Sr’s first ever tunnel under London (and quite how they got the grand piano down there is beyond me!). Although it only had three screenings this year, Waterloo’s 1901 Arts Club also looks to be a venue you need to keep an eye on, especially with pianist Meg Morley oft times accompanying there. Sadly, however, the Barbican’s gradual decline as a venue for quality silent screenings looks to be continuing, with just eight screenings this year compared to 11 last year and 20 in 2017. And their ‘programme’ for the forthcoming year doesn’t inspire confidence either.

Silent Film Highlights of 2019

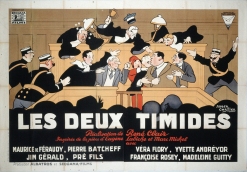

January kicked off with Ozu’s delightful classic I Was Born But…. (1932) at London’s Close-Up Cinema. The BFI opened the year with A Modern Dubarry (1927), something of an oddity which started as a romantic melodrama and ended more like the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup, but without the laughs. Meanwhile in Bristol, Slapstick brought us a rare Keaton in the form of The Battling Butler (1926), a surprisingly enjoyable Little Annie Rooney (1925) (thanks mainly to the playing of Gunter Buchwald, Frank Bockius and Marc Roos, the latter in particular who could seemingly make a trombone talk) and the great Les Deux Timides (1928). The Austrian Cultural Forum in London brought us the always eerie Hands of Orlac (1924) with Conrad Veidt, Bristol’s Cube brought us Valentino in The Sheik (1921) while Close-Up had a short but entertaining Finnish silent season

January kicked off with Ozu’s delightful classic I Was Born But…. (1932) at London’s Close-Up Cinema. The BFI opened the year with A Modern Dubarry (1927), something of an oddity which started as a romantic melodrama and ended more like the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup, but without the laughs. Meanwhile in Bristol, Slapstick brought us a rare Keaton in the form of The Battling Butler (1926), a surprisingly enjoyable Little Annie Rooney (1925) (thanks mainly to the playing of Gunter Buchwald, Frank Bockius and Marc Roos, the latter in particular who could seemingly make a trombone talk) and the great Les Deux Timides (1928). The Austrian Cultural Forum in London brought us the always eerie Hands of Orlac (1924) with Conrad Veidt, Bristol’s Cube brought us Valentino in The Sheik (1921) while Close-Up had a short but entertaining Finnish silent season  which closed with a rather strange comedy The Village Shoemakers (1923). February was a good one for The Golem, on tour with accompaniment by Harmonieband. The Kennington Bioscope scored big time with The Lovers of an Old Criminal (1927) featuring Anny Ondra in comedy mode before she became a Hitchcock heroine. Meanwhile, the BFI had an incredibly rare screening of Korean melodrama Crossroads of Youth (1934) accompanied by Korean ‘byeonsa’ narrator and musicians. Also on tour was Hershel 36 accompanying German science documentary Wonder of Creation (1925. Meanwhile, the Austrian Cultural Forum had a wonderful restoration of Pabst’s Joyless Street (1925). Down in Bristol, South West Silents were also on top form with A Throw of Dice (1929) and The Beloved Rogue (1927). In March, Assunta Spina (1915) starring awesome Italian diva Francesca Bertini was on tour accompanied by folk band The Badwills. Meanwhile, South West Silents

which closed with a rather strange comedy The Village Shoemakers (1923). February was a good one for The Golem, on tour with accompaniment by Harmonieband. The Kennington Bioscope scored big time with The Lovers of an Old Criminal (1927) featuring Anny Ondra in comedy mode before she became a Hitchcock heroine. Meanwhile, the BFI had an incredibly rare screening of Korean melodrama Crossroads of Youth (1934) accompanied by Korean ‘byeonsa’ narrator and musicians. Also on tour was Hershel 36 accompanying German science documentary Wonder of Creation (1925. Meanwhile, the Austrian Cultural Forum had a wonderful restoration of Pabst’s Joyless Street (1925). Down in Bristol, South West Silents were also on top form with A Throw of Dice (1929) and The Beloved Rogue (1927). In March, Assunta Spina (1915) starring awesome Italian diva Francesca Bertini was on tour accompanied by folk band The Badwills. Meanwhile, South West Silents were also on tour with The Blot (1921), accompanied by Lillian Henley. The Meg Morley Trio were on top form at the 1901 Arts Club accompanying The Man Who Laughs (1928). But the month belonged to HippFest, highlights of which included Pola Negri vamping it up in Forbidden Paradise (1924), the riotous Chinese martial arts epic Red Heroine (1929) and the early C T Dreyer comedy drama The Parson’s Widow, the last two of which saw John Sweeney on great form on piano. But the two festival high spots were probably Moulin Rouge (1928) with a truly stunning accompaniment from Jonny Best, Gunter Buchwald and Frank Bockius and Scandanavian epic Laila 1929) with a beautiful accompaniment from Marit and Rona.

were also on tour with The Blot (1921), accompanied by Lillian Henley. The Meg Morley Trio were on top form at the 1901 Arts Club accompanying The Man Who Laughs (1928). But the month belonged to HippFest, highlights of which included Pola Negri vamping it up in Forbidden Paradise (1924), the riotous Chinese martial arts epic Red Heroine (1929) and the early C T Dreyer comedy drama The Parson’s Widow, the last two of which saw John Sweeney on great form on piano. But the two festival high spots were probably Moulin Rouge (1928) with a truly stunning accompaniment from Jonny Best, Gunter Buchwald and Frank Bockius and Scandanavian epic Laila 1929) with a beautiful accompaniment from Marit and Rona.

Early April saw the Kennington Bioscope hosting another fascinating evening of 9.5mm films from Kevin Brownlow’s collecton, the high point of which was Leni Riefenstal in The White Hell of Piz Palu (1929). The British Silent Film Festival Symposium took place at King’s College, with rarities including The Maid of Cefn Ydfa (1914) and a recently rediscovered biopic of Mary Queen of Scots (????). The Kennington Bioscope scored again with their Silent Comedy Weekend, high spots including Lubitsch’s So This Is Paris (1926), Gloria Swanson in Stage Struck (1925) and Marion Davis gloriously funny in Show People (1928). Meanwhile, the Barbican showed another side of Anna Ondry’s early career with the melodrama White Paradise (1924). May saw the start of the BFI’s

Early April saw the Kennington Bioscope hosting another fascinating evening of 9.5mm films from Kevin Brownlow’s collecton, the high point of which was Leni Riefenstal in The White Hell of Piz Palu (1929). The British Silent Film Festival Symposium took place at King’s College, with rarities including The Maid of Cefn Ydfa (1914) and a recently rediscovered biopic of Mary Queen of Scots (????). The Kennington Bioscope scored again with their Silent Comedy Weekend, high spots including Lubitsch’s So This Is Paris (1926), Gloria Swanson in Stage Struck (1925) and Marion Davis gloriously funny in Show People (1928). Meanwhile, the Barbican showed another side of Anna Ondry’s early career with the melodrama White Paradise (1924). May saw the start of the BFI’s  Weimar season. The wonderfully funny Heaven on Earth (1927) had the misfortune of being bludgeoned to death by an overpowering musical accompaniment but at a second screening was left in the more than capable hands of Stephen Horne and the film’s true charm shone out. The season relied a bit too heavily on overly familiar titles such as The Golem (1920), Dr Mabuse (1922) and Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) but there were some less well known and rarely screened gems including Opium (1919), Song (1928), Chronicles of the Grey House (1925) and Student of Prague (1926). The BFI also hosted a weekend dedicated to their newly restored collection of Victorian film, with a welcome opportunity for those who missed it at last year’s London Film Festival to catch up with The Great Victorian Moving Picture Show. Keeping up with the Weimar theme, the Kennington Bioscope screened Hungarian Rhapsody (1928). Meanwhile, in Halifax, Square Chapel had a rare screening of Helen of Four Gates (1922), one of the few Cecil

Weimar season. The wonderfully funny Heaven on Earth (1927) had the misfortune of being bludgeoned to death by an overpowering musical accompaniment but at a second screening was left in the more than capable hands of Stephen Horne and the film’s true charm shone out. The season relied a bit too heavily on overly familiar titles such as The Golem (1920), Dr Mabuse (1922) and Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) but there were some less well known and rarely screened gems including Opium (1919), Song (1928), Chronicles of the Grey House (1925) and Student of Prague (1926). The BFI also hosted a weekend dedicated to their newly restored collection of Victorian film, with a welcome opportunity for those who missed it at last year’s London Film Festival to catch up with The Great Victorian Moving Picture Show. Keeping up with the Weimar theme, the Kennington Bioscope screened Hungarian Rhapsody (1928). Meanwhile, in Halifax, Square Chapel had a rare screening of Helen of Four Gates (1922), one of the few Cecil  Hepworth films to survive while Tyneside Cinema in Newcastle saw the start of a short tour of Italian diva classic Assunta Spina (1915). The BFI’s Weimar season continued in to June with the likes of The Cat’s Bridge (1927), the unbelievably bleak Mother Krause’s Journey To Happiness (1929) and Different From The Others (1919) with everyone’s favourite German actor, Conrad Veidt. But not to be out done, the Kennington Bioscope’s Silent Comedy Weekend also came up with Weimar expressionist tour de force The Stone Rider (1923). Amongst other gems, their weekend also included the stunning Marie Doro in Common Ground (1916), Marie Prevost at her comic best in On To Reno (1928) and Valentino himself in Monsieur Beaucaire (1924). Meanwhile, down in Dorset, the Dodge Brothers were wowing the Electric Palace crowd with Hell’s Hinges (1916).

Hepworth films to survive while Tyneside Cinema in Newcastle saw the start of a short tour of Italian diva classic Assunta Spina (1915). The BFI’s Weimar season continued in to June with the likes of The Cat’s Bridge (1927), the unbelievably bleak Mother Krause’s Journey To Happiness (1929) and Different From The Others (1919) with everyone’s favourite German actor, Conrad Veidt. But not to be out done, the Kennington Bioscope’s Silent Comedy Weekend also came up with Weimar expressionist tour de force The Stone Rider (1923). Amongst other gems, their weekend also included the stunning Marie Doro in Common Ground (1916), Marie Prevost at her comic best in On To Reno (1928) and Valentino himself in Monsieur Beaucaire (1924). Meanwhile, down in Dorset, the Dodge Brothers were wowing the Electric Palace crowd with Hell’s Hinges (1916).

July opened in classical style with a selection of silents focusing upon ancient Rome and Greece at the Bloomsbury Theatre. Galway’s town hall presented some Glimpses of Galway, captured in local travelogues of the 1920s. The Brunel Museum had the most apt screening of the month, Asquith’s classic Underground (1928), projected in a Victorian underground tunnel, while the Watershed in Bristol looked at the work of some early film pioneers including Alice Guy-Blache, William Friese-Green and R W Paul. In August, the now (hopefully) saved-from-commercialism Phoenix in Finchley had a good crowd to see Czech rarity Tonka of the Gallows (1930) with the beguiling Ita Rina. C T Dreyer’s classic The Passion of Joan of Arc

July opened in classical style with a selection of silents focusing upon ancient Rome and Greece at the Bloomsbury Theatre. Galway’s town hall presented some Glimpses of Galway, captured in local travelogues of the 1920s. The Brunel Museum had the most apt screening of the month, Asquith’s classic Underground (1928), projected in a Victorian underground tunnel, while the Watershed in Bristol looked at the work of some early film pioneers including Alice Guy-Blache, William Friese-Green and R W Paul. In August, the now (hopefully) saved-from-commercialism Phoenix in Finchley had a good crowd to see Czech rarity Tonka of the Gallows (1930) with the beguiling Ita Rina. C T Dreyer’s classic The Passion of Joan of Arc  (1928) got a rare outing down in Devon while The Cat and the Canary (1927) scared them all down in Chichester. September was dominated by the British Silent Film Festival at the Phoenix in Leicester. Amongst some rarely screened comedy gems, The Alley Cat (1929) and Tons of Money (1924) stood out while Phantom of the Moulin Rouge (1925) was an absurdest triumph. But the film of the festival had to be the shattering German melodrama Spring Awakening (1929). But in the ‘shattering melodrama’ stakes, the KenBio were not to be outdone, replying with early Victor Sjostrom social drama Ingeborg Holm (1913).

(1928) got a rare outing down in Devon while The Cat and the Canary (1927) scared them all down in Chichester. September was dominated by the British Silent Film Festival at the Phoenix in Leicester. Amongst some rarely screened comedy gems, The Alley Cat (1929) and Tons of Money (1924) stood out while Phantom of the Moulin Rouge (1925) was an absurdest triumph. But the film of the festival had to be the shattering German melodrama Spring Awakening (1929). But in the ‘shattering melodrama’ stakes, the KenBio were not to be outdone, replying with early Victor Sjostrom social drama Ingeborg Holm (1913).

October’s London Film Festival had but a thin selection of silents although these did include Jean Epstein marvel Finis Terrae (1929) as well as a rediscovered and restored Betty Balfour vehicle, Love, Life and Laughter (1923). Bristol’s Watershed was the venue for South West Silents own short Weimar season, opening with People on Sunday (1929). The Dodge Brothers were also playing again in Dorset, accompanying Beggars of Life (1928) while at the Cambridge Film Festival there were rare screenings of Light of Asia (1925) and Docks of Hamburg (1928). In Scotland, the Bo’ness Hippodrome began a short Autumn silent season with the utterly bizarre Seven Footsteps to Satan (1929) with amazing

October’s London Film Festival had but a thin selection of silents although these did include Jean Epstein marvel Finis Terrae (1929) as well as a rediscovered and restored Betty Balfour vehicle, Love, Life and Laughter (1923). Bristol’s Watershed was the venue for South West Silents own short Weimar season, opening with People on Sunday (1929). The Dodge Brothers were also playing again in Dorset, accompanying Beggars of Life (1928) while at the Cambridge Film Festival there were rare screenings of Light of Asia (1925) and Docks of Hamburg (1928). In Scotland, the Bo’ness Hippodrome began a short Autumn silent season with the utterly bizarre Seven Footsteps to Satan (1929) with amazing  accompaniment from Jane Gardner and Roddy Long (one of our films of the year from 2018). And back in Bristol, this time at the cathedral, Meg Morley was on top form accompanying The Man Who Laughs (1928). In November, Rob Roy (1922) went on tour in Scotland with a fine score from David Alison. Huddersfield University had some compelling French murderous intent with The Smiling Madame Beudet (1923) and Menilmontant (1926) while London’s Barbican focused upon genetic engineering and

accompaniment from Jane Gardner and Roddy Long (one of our films of the year from 2018). And back in Bristol, this time at the cathedral, Meg Morley was on top form accompanying The Man Who Laughs (1928). In November, Rob Roy (1922) went on tour in Scotland with a fine score from David Alison. Huddersfield University had some compelling French murderous intent with The Smiling Madame Beudet (1923) and Menilmontant (1926) while London’s Barbican focused upon genetic engineering and  the nature versus nurture debate with Alraune (1928) featuring Brigitte Helm at her iciest. The KenBio’s Cecil B DeMille Day had several gems from the master including Why Change Your Wife (1920) and Male and Female (1919), both starring la Swanson. In the West Country, South West Silents were busy screening the original Chicago (1927) in Clevedon and a rather strange and somewhat mysterious Anny Ondra vehicle Coming From The Dark (1921) at the Lansdown Public House. Meanwhile, in Lambourne, a fan so enamoured of Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927) decided to put on his own screening, all 332 minutes and with the wide-screen finale. What dedication. The KenBio’s main feature of the month was Claire (1924) starring Lya de Putti but of more interest was the evening’s support film, The Abyss (1910), Asta Neilsen’s debut film appearance. Although something of a thin month, December did include Jean Renoir’s debut feature Nana (1926) at the Regent Street Cinema and some Eerie Tales (1919), an early horror compendium at the BFI. There was also time for Peter Pan (1924) in Reading and the month ended with The Great White Silence (1924) at The Palace, Broadstairs.

the nature versus nurture debate with Alraune (1928) featuring Brigitte Helm at her iciest. The KenBio’s Cecil B DeMille Day had several gems from the master including Why Change Your Wife (1920) and Male and Female (1919), both starring la Swanson. In the West Country, South West Silents were busy screening the original Chicago (1927) in Clevedon and a rather strange and somewhat mysterious Anny Ondra vehicle Coming From The Dark (1921) at the Lansdown Public House. Meanwhile, in Lambourne, a fan so enamoured of Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927) decided to put on his own screening, all 332 minutes and with the wide-screen finale. What dedication. The KenBio’s main feature of the month was Claire (1924) starring Lya de Putti but of more interest was the evening’s support film, The Abyss (1910), Asta Neilsen’s debut film appearance. Although something of a thin month, December did include Jean Renoir’s debut feature Nana (1926) at the Regent Street Cinema and some Eerie Tales (1919), an early horror compendium at the BFI. There was also time for Peter Pan (1924) in Reading and the month ended with The Great White Silence (1924) at The Palace, Broadstairs.

Our Top Ten Of The Year (Plus A Couple Of Duds And A Few Regrets)

We got back on form this year, managing to squeeze in 124 silent film screenings, nearly all with live musical accompaniment, compared to just 99 last year. Trying to pick out just ten of these remains just as difficult a task as in previous years. Some films came, oh, so close to making the final cut that they deserve mention, particularly Joyless Street at the Austrian Cultural Forum, Throw of Dice at Bristol Museum and The Stone Rider and Ingeborg Holm both at KenBio.

But our ten favourites of the year (not necessarily the ten best films, but those screenings and accompaniment which we most enjoyed) are as follows (by screening date order);

Lovers Of An Old Criminal (Dir. Svatopluk Innemann, Cz, 1927) 6 February at Kennington Bioscope/Cinema Museum with live piano accompaniment by John Sweeney and Cyrus Gabrysch. For those of us who had only seen Anny Ondra in Hitchcock melodramas then the sight of her, the cigar smoking, outrageously dressed femme fatale in this frenetic comedy is a revelation. The film is frequently laugh out loud funny, sometimes matching the style of Lubitsch, often matching the pace of Keystone. Male lead Vlasta Burian may be unknown in the West but he remains a national treasure in the Czech Republic and with good reason, his comic timing was perfection itself. Pianists John Sweeney and Cyrus Gabrysch both played solo to perfection, managing a seamless transition between players mid-film (in possibly a silent film first!!?)

Lovers Of An Old Criminal (Dir. Svatopluk Innemann, Cz, 1927) 6 February at Kennington Bioscope/Cinema Museum with live piano accompaniment by John Sweeney and Cyrus Gabrysch. For those of us who had only seen Anny Ondra in Hitchcock melodramas then the sight of her, the cigar smoking, outrageously dressed femme fatale in this frenetic comedy is a revelation. The film is frequently laugh out loud funny, sometimes matching the style of Lubitsch, often matching the pace of Keystone. Male lead Vlasta Burian may be unknown in the West but he remains a national treasure in the Czech Republic and with good reason, his comic timing was perfection itself. Pianists John Sweeney and Cyrus Gabrysch both played solo to perfection, managing a seamless transition between players mid-film (in possibly a silent film first!!?)

Laila (Dir. George Schneevoigt, Nor, 1929) – 21 March at the Hippodrome Cinema, Bo’ness with live accompaniment by Marit and Rona. A story of ethnic tension set amongst the Sami people of northern Scandanavia this is a film which is stunning to look at, beautifully acted and with breathtaking action sequences. Mona Martenson (a drama class contemporary of Garbo who turned down the opportunity to go to Hollywood) in the title role is marvelous as is Peter Malberg as the Sami leader. With a beautiful and wonderfully sympathetic score from Norwegian/Scottish folk duo Marit and Rona this film was 146 minutes of pure joy.

Laila (Dir. George Schneevoigt, Nor, 1929) – 21 March at the Hippodrome Cinema, Bo’ness with live accompaniment by Marit and Rona. A story of ethnic tension set amongst the Sami people of northern Scandanavia this is a film which is stunning to look at, beautifully acted and with breathtaking action sequences. Mona Martenson (a drama class contemporary of Garbo who turned down the opportunity to go to Hollywood) in the title role is marvelous as is Peter Malberg as the Sami leader. With a beautiful and wonderfully sympathetic score from Norwegian/Scottish folk duo Marit and Rona this film was 146 minutes of pure joy.

The Parson’s Widow (Dir. C T Dreyer, Swe, 1920) – 23 March at the Hippodrome Cinema, Bo’ness with live piano accompaniment by John Sweeney. When the new parson realises he has to marry his predecessor’s widow, the job looses some of its sparkle, and his fiancé isn’t pleased either! In some ways, a very slight film but at the same time beautifully shot, staged and acted. The comedy is very gentle but funny nevertheless. Hildur Carlberg is superb as the widow but her goodbyes will break your heart. John Sweeney on piano provided the gentlest of scores, beautifully capturing the humour, drama and eventual heartbreak on screen.

The Parson’s Widow (Dir. C T Dreyer, Swe, 1920) – 23 March at the Hippodrome Cinema, Bo’ness with live piano accompaniment by John Sweeney. When the new parson realises he has to marry his predecessor’s widow, the job looses some of its sparkle, and his fiancé isn’t pleased either! In some ways, a very slight film but at the same time beautifully shot, staged and acted. The comedy is very gentle but funny nevertheless. Hildur Carlberg is superb as the widow but her goodbyes will break your heart. John Sweeney on piano provided the gentlest of scores, beautifully capturing the humour, drama and eventual heartbreak on screen.

Moulin Rouge (Dir. E A Dupont, UK/Ger, 1928) – 24 March at the Hippodrome Cinema, Bo’ness with live accompaniment by Jonny Best, Gunter Buchwald and Frank Bockius. When a romantic melodrama involves daughter’s fiancé falling for daughter’s mother then you know you are on somewhat dodgy ground. Although interesting, this is perhaps not a great picture, especially when it switches from melodrama to chase film. But what made this screening special was the accompaniment from Messrs. Best, Buchwald and Bockius. The film’s opening sequence is an extended compendium of variety acts performing at the Moulin Rouge and the accompaniment is a tour de force in a breathtaking range of musical styles to match the on-screen performances. Not that the accompaniment lets up when the melodrama starts and it goes on to reach another crescendo during the extended chase sequence, leaving the audience thrilled, overwhelmed and exhausted. A fantastic evening.

Moulin Rouge (Dir. E A Dupont, UK/Ger, 1928) – 24 March at the Hippodrome Cinema, Bo’ness with live accompaniment by Jonny Best, Gunter Buchwald and Frank Bockius. When a romantic melodrama involves daughter’s fiancé falling for daughter’s mother then you know you are on somewhat dodgy ground. Although interesting, this is perhaps not a great picture, especially when it switches from melodrama to chase film. But what made this screening special was the accompaniment from Messrs. Best, Buchwald and Bockius. The film’s opening sequence is an extended compendium of variety acts performing at the Moulin Rouge and the accompaniment is a tour de force in a breathtaking range of musical styles to match the on-screen performances. Not that the accompaniment lets up when the melodrama starts and it goes on to reach another crescendo during the extended chase sequence, leaving the audience thrilled, overwhelmed and exhausted. A fantastic evening.

Hungarian Rhapsody (Dir. Hans Schwarz, Ger, 1928) – 8 May at Kennington Bioscope/Cinema Museum with live piano accompaniment from John Sweeney. The story of an impoverished junior officer torn in his affections between his fiance and the wife of his commanding officer. When released in Germany in 1928, it was one of the most popular films of the year and its not difficult to see why. Right from the opening scene as hundreds of workers cut wheat in the fields it looks stunning. The big ensemble scenes are brilliantly staged with breathtakingly fluid camera movement. And amongst the film’s two female leads, while Dita Parlo may have had the youthful good looks it was Lil Dagover who won hands down when it came to sensual swagger. But as good as the film was, enjoyment of it was greatly enhanced by a brilliant live performance from John Sweeney. In particular, his accompaniment of the dance scenes in the officer’s mess and at the harvest festival celebrations was an absolute tour de force and as the raucous applause at the film’s finale indicated, it was greatly appreciated by the whole audience.

Hungarian Rhapsody (Dir. Hans Schwarz, Ger, 1928) – 8 May at Kennington Bioscope/Cinema Museum with live piano accompaniment from John Sweeney. The story of an impoverished junior officer torn in his affections between his fiance and the wife of his commanding officer. When released in Germany in 1928, it was one of the most popular films of the year and its not difficult to see why. Right from the opening scene as hundreds of workers cut wheat in the fields it looks stunning. The big ensemble scenes are brilliantly staged with breathtakingly fluid camera movement. And amongst the film’s two female leads, while Dita Parlo may have had the youthful good looks it was Lil Dagover who won hands down when it came to sensual swagger. But as good as the film was, enjoyment of it was greatly enhanced by a brilliant live performance from John Sweeney. In particular, his accompaniment of the dance scenes in the officer’s mess and at the harvest festival celebrations was an absolute tour de force and as the raucous applause at the film’s finale indicated, it was greatly appreciated by the whole audience.

Heaven On Earth (Dir. Reinhold Schünzel/Alfred Schirokauer, Ger, 1927) – 13 May at BFI Southbank with live piano accompaniment by Stephen Horne. When we first saw this comedy a couple of weeks earlier it was completely overwhelmed by a wholly inappropriate live accompaniment. But this story of deception, cross dressing and mistaken identity clearly deserved another look and this time in the reliable hands of accompanist Stephen Horne the film fairly fizzed with comic delight, not least the female dance troop disguised as English boarding school girls, the increasingly decrepit butler, the trained monkey and Schunzel’s appearance in drag.

Heaven On Earth (Dir. Reinhold Schünzel/Alfred Schirokauer, Ger, 1927) – 13 May at BFI Southbank with live piano accompaniment by Stephen Horne. When we first saw this comedy a couple of weeks earlier it was completely overwhelmed by a wholly inappropriate live accompaniment. But this story of deception, cross dressing and mistaken identity clearly deserved another look and this time in the reliable hands of accompanist Stephen Horne the film fairly fizzed with comic delight, not least the female dance troop disguised as English boarding school girls, the increasingly decrepit butler, the trained monkey and Schunzel’s appearance in drag.

Tonka of the Gallows (Dir. Karel Anton, Cz, 1930) – 4 August at the Phoenix, East Finchley with live musical accompaniment from Stephen Horne. Tonka is a prostitute whose life spirals downwards when an impulsive act of kindness marks her out as a pariah. Ita Rina gives an incredible performance as Tonka, ground down by rejection,world weariness haunting her very appearance. It is such a shame that she is not better known and that her film appearances were so few, forced by her husband to choose marriage over career. Accompanist Stephen Horne caught the melancholy and eventual tragedy of Tonka’s situation perfectly.

Tonka of the Gallows (Dir. Karel Anton, Cz, 1930) – 4 August at the Phoenix, East Finchley with live musical accompaniment from Stephen Horne. Tonka is a prostitute whose life spirals downwards when an impulsive act of kindness marks her out as a pariah. Ita Rina gives an incredible performance as Tonka, ground down by rejection,world weariness haunting her very appearance. It is such a shame that she is not better known and that her film appearances were so few, forced by her husband to choose marriage over career. Accompanist Stephen Horne caught the melancholy and eventual tragedy of Tonka’s situation perfectly.

Spring Awakening (Dir, Richard Oswald, Ger, 1929) – 13 September at the Phoenix Cinema, Leicester with live musical accompaniment by Stephen Horne. Although director Richard Oswald’s film version differs significantly from Wedekin’s original text in several key aspects, it still manages to convey the same emotional and dramatic impact in its examination of awakening adolescent sexuality in an era of sexual oppression and ignorance.The performances of all of the cast are exceptional. Toni van Eyck was superb as the innocent and over-protected Wendla in her first major film roll as was Carl Bauhaus as the doomed Moritz. In yet another sinister role, Fritz Rasp was also excellent as the repressed and repressive teacher (was there ever a film in which Rasp played a sympathetic character?). With Stephen Horne again on top form, layering on the drama and the tension, the film was probably the highlight of this year’s British Silent Film Festival.

Spring Awakening (Dir, Richard Oswald, Ger, 1929) – 13 September at the Phoenix Cinema, Leicester with live musical accompaniment by Stephen Horne. Although director Richard Oswald’s film version differs significantly from Wedekin’s original text in several key aspects, it still manages to convey the same emotional and dramatic impact in its examination of awakening adolescent sexuality in an era of sexual oppression and ignorance.The performances of all of the cast are exceptional. Toni van Eyck was superb as the innocent and over-protected Wendla in her first major film roll as was Carl Bauhaus as the doomed Moritz. In yet another sinister role, Fritz Rasp was also excellent as the repressed and repressive teacher (was there ever a film in which Rasp played a sympathetic character?). With Stephen Horne again on top form, layering on the drama and the tension, the film was probably the highlight of this year’s British Silent Film Festival.

The Phantom of the Moulin Rouge (Dir Rene Clair, Fr, 1925) – 14 September at the Phoenix Cinema, Leicester with live musical accompaniment by Stephen Horne (piano, accordian and flute) and Elizabeth Jane Baldry (harp). The story of a spirit freed from his body and initially reluctant to return. Unlike Clair’s earlier films, this has a much more conventional narrative and despite the strong fantasy element there remains a clear focus on the central human drama. However, it is also apparent that he is still experimenting with cinematic techniques which accounts for the film sometimes veering wildly between genres. At times it is a knockabout comedy, at other times a story of great poignancy while the finale is a classic against-the-clock chase sequence. While Stephen’s accordion perfectly matched the frivolity of the Moulin Rouge dance scenes, Elizabeth’s playing of the harp caught precisely the eeriness of the floating disembodied spirit. And who would have thought that the harp could be considered a percussion instrument. Great fun.

The Phantom of the Moulin Rouge (Dir Rene Clair, Fr, 1925) – 14 September at the Phoenix Cinema, Leicester with live musical accompaniment by Stephen Horne (piano, accordian and flute) and Elizabeth Jane Baldry (harp). The story of a spirit freed from his body and initially reluctant to return. Unlike Clair’s earlier films, this has a much more conventional narrative and despite the strong fantasy element there remains a clear focus on the central human drama. However, it is also apparent that he is still experimenting with cinematic techniques which accounts for the film sometimes veering wildly between genres. At times it is a knockabout comedy, at other times a story of great poignancy while the finale is a classic against-the-clock chase sequence. While Stephen’s accordion perfectly matched the frivolity of the Moulin Rouge dance scenes, Elizabeth’s playing of the harp caught precisely the eeriness of the floating disembodied spirit. And who would have thought that the harp could be considered a percussion instrument. Great fun.

The Man Who Laughs (Dir. Paul Leni, USA, 1928) – 31 October at Bristol Cathedral with live piano accompaniment by Meg Morley. It might be Hollywood grand guignol, but its done with some style (and scale). Conrad Veidt is the nobleman’s son with a permanent smile carved on his face,Mary Philbin is the blind girl who loves him. Veidt manages to carry off his role quite convincingly (and in the process influences the creation of Batman’s nemesis The Joker) but Philbin has little to do. Much more fun is Olga Baklanova as the evil countess and Brandon Hurst as the chief villain. I had seen this film earlier in the year with accompaniment by the Meg Morley Trio and for a film set in 17th century England the jazz based score worked surprisingly well. But today Meg was on her own and opted for a more classically focused score on the cathedral Steinway. This she achieved to perfection, matching both the more intimate and often pathos infused scenes as well as the thunderous climactic chase finale.

The Man Who Laughs (Dir. Paul Leni, USA, 1928) – 31 October at Bristol Cathedral with live piano accompaniment by Meg Morley. It might be Hollywood grand guignol, but its done with some style (and scale). Conrad Veidt is the nobleman’s son with a permanent smile carved on his face,Mary Philbin is the blind girl who loves him. Veidt manages to carry off his role quite convincingly (and in the process influences the creation of Batman’s nemesis The Joker) but Philbin has little to do. Much more fun is Olga Baklanova as the evil countess and Brandon Hurst as the chief villain. I had seen this film earlier in the year with accompaniment by the Meg Morley Trio and for a film set in 17th century England the jazz based score worked surprisingly well. But today Meg was on her own and opted for a more classically focused score on the cathedral Steinway. This she achieved to perfection, matching both the more intimate and often pathos infused scenes as well as the thunderous climactic chase finale.

Alraune ( aka Unholy Love, Mandrake, or A Daughter of Destiny) (Dir. Henrik Galeen, Ger, 1928) – 10 November at Barbican, London with live musical accompaniment from Stephen Horne and Martin Pyne. This little known story of genetic manipulation and artificial insemination is a reworking of the old nature versus nurture argument. Ostensibly a science fiction film it is really a more orthodox mystery drama. Star Brigitte Helm was seemingly born to play the cold, emotionless Alraune of the title, a task which she carries out to perfection. The film’s subject matter and the somewhat suspect central father-daughter relationship clearly resulted in considerable censorship difficulties and the picture still appears incomplete but is nevertheless fascinating if perhaps not a classic. With almost a dozen instruments between them Stephen Horne and Martin Pyne produced a stunning accompaniment. And while Martin often seemingly plays more of a supporting percussion role when working with other musicians, here he clearly relished a leading role, particularly when playing the vibraphone (and who would have thought you could play a vibraphone with a violin bow!)

Alraune ( aka Unholy Love, Mandrake, or A Daughter of Destiny) (Dir. Henrik Galeen, Ger, 1928) – 10 November at Barbican, London with live musical accompaniment from Stephen Horne and Martin Pyne. This little known story of genetic manipulation and artificial insemination is a reworking of the old nature versus nurture argument. Ostensibly a science fiction film it is really a more orthodox mystery drama. Star Brigitte Helm was seemingly born to play the cold, emotionless Alraune of the title, a task which she carries out to perfection. The film’s subject matter and the somewhat suspect central father-daughter relationship clearly resulted in considerable censorship difficulties and the picture still appears incomplete but is nevertheless fascinating if perhaps not a classic. With almost a dozen instruments between them Stephen Horne and Martin Pyne produced a stunning accompaniment. And while Martin often seemingly plays more of a supporting percussion role when working with other musicians, here he clearly relished a leading role, particularly when playing the vibraphone (and who would have thought you could play a vibraphone with a violin bow!)

OK, so the more eagle-eyed amongst you will have noticed that this top ten list is actually eleven strong. But really, we just could not make the final cut and, hey, its our list so our rules!! And if our feet were to be held to the fire in order to name but a single favourite film of the year then it was a close call but we’d have to go for Laila (1929), screened at HippFest in March with accompaniment by Marit and Rona. Not just a wonderful film and a beautiful score but film and music blended perfectly together to be so much more than the sum of the parts.

OK, so the more eagle-eyed amongst you will have noticed that this top ten list is actually eleven strong. But really, we just could not make the final cut and, hey, its our list so our rules!! And if our feet were to be held to the fire in order to name but a single favourite film of the year then it was a close call but we’d have to go for Laila (1929), screened at HippFest in March with accompaniment by Marit and Rona. Not just a wonderful film and a beautiful score but film and music blended perfectly together to be so much more than the sum of the parts.

Anyway, having got the Top Ten (or eleven!) out of the way, what of the not so good. Biggest dud of the year had to go to the wayward accompaniment of the BFI’s first screening of Heaven On Earth (1927). Such a farce laden comedy of manners, deserved accompaniment with a certain lightness of touch. Instead, it got not so much a sledge-hammer as a wrecking ball. Rather than the music accompanying the film, the film was instead demoted to little more than a visual backdrop to the music and honestly, it was awful. It took another screening with Stephen Horne to show how it should be done. And bad venue planning of the year also had to go to BFI. Crossroads of Youth (1934) had the potential to be a fascinating evening, an incredibly rare late Korean silent, plus Korean musicians and ‘byeonsa’ narrator flown in especially from Korea for the event. But then to arrange just a single screening and that in the small NFT 3 auditorium, which was almost immediately sold out, meant that so many people missed out on this unique event.

And what else did we miss out on this year. Well, we missed not one but two opportunities to see Britain’s own ‘Queen of Happiness’, Betty Balfour in the rediscovered and restored Love, Life and Laughter (1923). Then there was the rarely screened Oscar Micheaux melodrama Within Our Gates (1920) and the gritty German thriller Docks of Hamburg (1928). And although it crops up fairly regularly, fate always seems to conspire to prevent us catching up with He Who Gets Slapped (1924). But perhaps better luck this coming year.

And that pretty well wraps up this review of the year, other than to express, as usual, our thanks to all of those venues, programmers, projectionists, accompanists, hosts, speakes and volunteers who give so generously of their time, energies and skills to make these silent events happen. Your efforts really are appreciated.