BFI Southbank, London

4 May 2019

(Warning; Spoilers throughout)

Tonight’s installment in the BFI’s much welcomed Weimar Cinema season takes us back almost to the earliest years of this particular cinematic era, with the sensationalist Opium (1919), directed by Robert Reinart and made at a time when censorship in post-war Germany was at its most relaxed.

Tonight’s installment in the BFI’s much welcomed Weimar Cinema season takes us back almost to the earliest years of this particular cinematic era, with the sensationalist Opium (1919), directed by Robert Reinart and made at a time when censorship in post-war Germany was at its most relaxed.

In a story told in six acts, the film opens with European Professor Gesellius visiting China as he seeks to uncover the medicinal benefits of opium. Visiting an opium den he encounters a young woman, Sin (Sybil Morel) who seeks his help in escaping the clutches of drug den owner Nung-Tschang (Werner Krauss). Nung reveals to Gesellius that Sin was the product of an illicit relationship between Nung’s wife and another visiting European, Dr Richard Armstrong (Friedrich Kuhne). In revenge, Nung killed his wife and turned Armstrong into a hopeless drug addict. After Gesellius is imprisoned by Nung, it is Sin who in turn helps him escape and the two flee to Europe while Nung swears revenge.

In a story told in six acts, the film opens with European Professor Gesellius visiting China as he seeks to uncover the medicinal benefits of opium. Visiting an opium den he encounters a young woman, Sin (Sybil Morel) who seeks his help in escaping the clutches of drug den owner Nung-Tschang (Werner Krauss). Nung reveals to Gesellius that Sin was the product of an illicit relationship between Nung’s wife and another visiting European, Dr Richard Armstrong (Friedrich Kuhne). In revenge, Nung killed his wife and turned Armstrong into a hopeless drug addict. After Gesellius is imprisoned by Nung, it is Sin who in turn helps him escape and the two flee to Europe while Nung swears revenge.

Returning home to his wife Maria (Hanna Ralph),Gesellius continues his research into opium while Sin, now renamed Magdalena is employed as a nurse at Gesellius’ sanatorium for recovering opium addicts But unbeknownst to the professor, his wife is engaged in an illicit affair with Gesellius’ protégé Dr Richard Armstrong Jr. (Conrad Veidt) (Image, right). Shortly after, the disheveled and still drug-addicted Armstrong Sr. turns up and is admitted to the sanatorium and Gesellius realises that he is the father of both his protégé and of Sin/Magdalena.

disheveled and still drug-addicted Armstrong Sr. turns up and is admitted to the sanatorium and Gesellius realises that he is the father of both his protégé and of Sin/Magdalena.

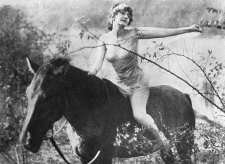

When Armstrong Jr. is injured in a riding accident it leads to Gesellius discovering the truth about his wife’s affair with him (image below left). Also reappearing is Nung who warns Maria that Gesellius may seek revenge against the injured Armstrong Jr. Although Gesellius reassures her that Armstrong Jr. will survive, in his depression the professor takes opium after which he dreams of killing him. Meanwhile, Armstrong Jr. himself is racked with guilt over his affair with his mentor’s wife and decides to take his own life. He writes a suicide note to Maria concealed within the locket of her infant daughter but the child doesn’t understand to deliver it to Maria. When Armstrong Jr. is discovered dead , Gesellius believes he may in fact have killed him in  his drugged state. Nung also convinces the now recovered Armstrong Sr. that Gesellius was responsible for his son’s death. To escape these accusations Gesellius decides to take up a government offer to continue his research in India, taking Magdalena with him.

his drugged state. Nung also convinces the now recovered Armstrong Sr. that Gesellius was responsible for his son’s death. To escape these accusations Gesellius decides to take up a government offer to continue his research in India, taking Magdalena with him.

In India, Gesellius remains racked with guilt over Armstrong Jr.’s death. Nung reappears, offering him opium as a means of escape. In an attempt to save Gesellius from his addiction, Magdalena says it was she who killed Armstrong Jr. At a social gathering, the wife of a local maharajah takes a fancy to Gesellius and invites the now opium addicted professor to see her in secret. Nung reappears to tell the maharajah of his wife’s apparent infidelity and he orders Gesellius’ arrest. As punishment he is tied to a horse and cast out into the lion infested jungle. Rescued by Magdalena and his trusted manservant (the latter subsequently being killed by Nung) Gesellius and Magdalena escape once more back to Europe.

When Armstrong Sr., now running the sanatorium, learns of Magdalena’s apparent confession to murdering his son he reports this to the police and she is arrested and sentenced to death. Nung again reappears, this time to tell Armstrong Sr. that Magdalena is his own daughter and that it is his actions which have condemned her to death. Although Nung’s revenge on Armstrong Sr. is now apparently complete he decides to engineer Magdalene’s escape but is killed by the police in the process. Back at his home, as the now hopelessly addicted Gesellius embraces his infant daughter he discovers Armstrong Jr.’s suicide note still concealed in her locket. Magdalena is released and reconciled with her father while Gesellius succumbs to his opium addiction and in death is reunited with his faithful manservant.

Writer-Director Robert Reinert is a virtually forgotten figure in German film history, perhaps surprisingly given that some of his films achieved considerable popular and critical acclaim. He  began his career in cinema as a writer, first of the six-part feature-length serial Homunculus (1916), the story of a creature manufactured in a laboratory, not a robot but a living being, a perfect man. Becoming the most popular serial made in wartime Germany the film was also a portent of Reinert’s subsequent directorial style emphasising the metaphorical and the philosophical, with the Homonculus portrayed here as a sort of Nietzschen Superman figure. Moving on to direct, Reinert was responsible for some of the most popular German melodramas of 1917 and 1918 becoming in the process a hugely influential figure at the Deutsche-Bioscop Film Company where he supervised multiple directorial projects. But by the end of 1918 he had left Deutsche-Bioscop to

began his career in cinema as a writer, first of the six-part feature-length serial Homunculus (1916), the story of a creature manufactured in a laboratory, not a robot but a living being, a perfect man. Becoming the most popular serial made in wartime Germany the film was also a portent of Reinert’s subsequent directorial style emphasising the metaphorical and the philosophical, with the Homonculus portrayed here as a sort of Nietzschen Superman figure. Moving on to direct, Reinert was responsible for some of the most popular German melodramas of 1917 and 1918 becoming in the process a hugely influential figure at the Deutsche-Bioscop Film Company where he supervised multiple directorial projects. But by the end of 1918 he had left Deutsche-Bioscop to  form his own Monumental Film Company, intended to produce ‘monumental’ films. The first of these was Opium (about which more later). The second was Nerves (1919), the story of a battle between politicians from left and right which weaves in a wider societal story as well as more personal family drama. The film was a considerable critical success at the time but a major box office failure, particularly given the resources expended on its production. With a disorienting, highly experimental style and pre-dating The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), Nerves would surely have been hailed as a precursor of German Expressionist cinema had it had been more widely seen and better preserved. But for Reinert this was the first of several major film projects which failed to gain popular appeal and, with his own production company failing, he took up a writing role at the UFA studios in Berlin before his premature death from a heart attack in 1928.

form his own Monumental Film Company, intended to produce ‘monumental’ films. The first of these was Opium (about which more later). The second was Nerves (1919), the story of a battle between politicians from left and right which weaves in a wider societal story as well as more personal family drama. The film was a considerable critical success at the time but a major box office failure, particularly given the resources expended on its production. With a disorienting, highly experimental style and pre-dating The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), Nerves would surely have been hailed as a precursor of German Expressionist cinema had it had been more widely seen and better preserved. But for Reinert this was the first of several major film projects which failed to gain popular appeal and, with his own production company failing, he took up a writing role at the UFA studios in Berlin before his premature death from a heart attack in 1928.

Unlike Nerves, however, Opium is more a conventional melodrama, albeit with a somewhat overblown and sensationalist style (and then some!). It is suffused throughout with the hugely over-theatrical manner of acting still so characteristic of the era with, perhaps, only Hanna Ralph as Gesellius’ wife achieving a more moderated style. Then there is Nung Tschang, who repeatedly appears as if from nowhere at all the key moments with his desire for revenge (or is it just to move the plot along?). And why on earth when he appears to have succeeded would he then try to free Sin and end up getting killed in the process. And what about that lion infested forest…in India! Clearly the opium was kicking in by now, or was it because the local zoo was all out of tigers!

Unlike Nerves, however, Opium is more a conventional melodrama, albeit with a somewhat overblown and sensationalist style (and then some!). It is suffused throughout with the hugely over-theatrical manner of acting still so characteristic of the era with, perhaps, only Hanna Ralph as Gesellius’ wife achieving a more moderated style. Then there is Nung Tschang, who repeatedly appears as if from nowhere at all the key moments with his desire for revenge (or is it just to move the plot along?). And why on earth when he appears to have succeeded would he then try to free Sin and end up getting killed in the process. And what about that lion infested forest…in India! Clearly the opium was kicking in by now, or was it because the local zoo was all out of tigers!

But this was not to say that the film wasn’t without its plus-points. Some of the cinematography was hugely impressive, in particular the spectacular depth of field achieved by cameraman Helmar Lerski, Reinert’s regular man behind the camera at that time. However, although some scenes manifestly benefited from this treatment, others looked as if they had been set up simply because they could be. Why, for example, was a glass displayed so deliberately and prominently on the professor’s lectern as he gave a lecture other than to highlight the fact that it could be held in focus along with the most distant members of the watching audience. Given that Lerski started out as a professional portrait photographer it is also perhaps not surprising that many of the scenes end in a tableau like effect, almost as with a

But this was not to say that the film wasn’t without its plus-points. Some of the cinematography was hugely impressive, in particular the spectacular depth of field achieved by cameraman Helmar Lerski, Reinert’s regular man behind the camera at that time. However, although some scenes manifestly benefited from this treatment, others looked as if they had been set up simply because they could be. Why, for example, was a glass displayed so deliberately and prominently on the professor’s lectern as he gave a lecture other than to highlight the fact that it could be held in focus along with the most distant members of the watching audience. Given that Lerski started out as a professional portrait photographer it is also perhaps not surprising that many of the scenes end in a tableau like effect, almost as with a  static photograph or a painting. And although tinting by this time was nothing unusual, the scenes shot in the opium den were given added piquancy with the bold red colouring.

static photograph or a painting. And although tinting by this time was nothing unusual, the scenes shot in the opium den were given added piquancy with the bold red colouring.

Then there were the scenes seeking to represent the effects of opium usage, sometimes shot as a double exposure with rippling water overlays conveying a feel of peaceful tranquillity. At other times there were scantily clad maidens reminiscent of something  rom A Midsummer Night’s Dream, replete with Puck like figures …and goats for some reason (perhaps drawing a connection between opium addiction, the devil and hell)! The film was also notable for its considerable production values. Made only shortly after the end of the war when finances were stretched, this was a film of considerable budget. While the scenes set in China may have had something of an anywhere feel to them, those in India were much more convincing (in fact, all the exteriors were shot outside Berlin) and with a significantly larger cast (elephants and all).

rom A Midsummer Night’s Dream, replete with Puck like figures …and goats for some reason (perhaps drawing a connection between opium addiction, the devil and hell)! The film was also notable for its considerable production values. Made only shortly after the end of the war when finances were stretched, this was a film of considerable budget. While the scenes set in China may have had something of an anywhere feel to them, those in India were much more convincing (in fact, all the exteriors were shot outside Berlin) and with a significantly larger cast (elephants and all).

Despite its multi-racial storyline all of the key players in Opium were German or Austrian.  Eduard von Winterstein ( Gesellius, image right with Sybil Morel), who would also star in Nerves, was a renowned stage actor who went on to make over a hundred films, remaining a popular star of German cinema until his last appearance in 1959. Playing Nung-Tschang was a doyen of the German stage, Werner Krauss (image below left), perhaps best remembered in silent film history as Dr Caligari in Robert Wiene’s 1920 classic of cinematic expressionism. His distinguished film and stage

Eduard von Winterstein ( Gesellius, image right with Sybil Morel), who would also star in Nerves, was a renowned stage actor who went on to make over a hundred films, remaining a popular star of German cinema until his last appearance in 1959. Playing Nung-Tschang was a doyen of the German stage, Werner Krauss (image below left), perhaps best remembered in silent film history as Dr Caligari in Robert Wiene’s 1920 classic of cinematic expressionism. His distinguished film and stage  career would continue until curtailed as a result of his anti-semitism and Nazi propaganda work. A relatively youthful Conrad Veidt played the young Richard Armstrong (image, below right). Given his debut in film by Robert Reinert in 1917 with Wenn Tote Sprechen, Veidt became a Reinart regular in films prior to Opium although he also worked at this time for other distinguished directors including Robert Wiene, EA Dupont and Paul Leni. Clearly reflecting the easing of censorship restrictions immediately after the war, in

career would continue until curtailed as a result of his anti-semitism and Nazi propaganda work. A relatively youthful Conrad Veidt played the young Richard Armstrong (image, below right). Given his debut in film by Robert Reinert in 1917 with Wenn Tote Sprechen, Veidt became a Reinart regular in films prior to Opium although he also worked at this time for other distinguished directors including Robert Wiene, EA Dupont and Paul Leni. Clearly reflecting the easing of censorship restrictions immediately after the war, in  1919 alone he appeared in films entitled Prostitution, Those Who Sell Themselves, Whipped and Madness, as well as Different From The Others which is now regarded as a ground-breaking film in its sympathetic portrayal of homosexuality, But it was playing Cesare in Caligari that really set off Veidt’s career. His film credits in the 1920s were a virtual history of Weimar cinema including Waxworks (1924), The Hands of Orlac (1924) and The Student of Prague (1926) but by the late 1920s he had been snapped up by Hollywood with his most significant silent being The Man Who Laughs (1928). Veidt was to die prematurely of a heart attack shortly after completion of what was probably his best remembered talkie role, as the sinister Major Heinrich Strasser in Casablanca (1942). Lastly, Hanna Ralph (Frau Gesellius) was another actor with considerable stage experience. She starred in several films opposite Emil Jannings who she subsequently married, played Queen Brunhilda in Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen (1924) and even played opposite Lionel Barrymore in the Herbert Wilcox directed romantic melodrama Decameron Nights (1924). But with the coming of sound she largely refocused her acting career back on stage work.

1919 alone he appeared in films entitled Prostitution, Those Who Sell Themselves, Whipped and Madness, as well as Different From The Others which is now regarded as a ground-breaking film in its sympathetic portrayal of homosexuality, But it was playing Cesare in Caligari that really set off Veidt’s career. His film credits in the 1920s were a virtual history of Weimar cinema including Waxworks (1924), The Hands of Orlac (1924) and The Student of Prague (1926) but by the late 1920s he had been snapped up by Hollywood with his most significant silent being The Man Who Laughs (1928). Veidt was to die prematurely of a heart attack shortly after completion of what was probably his best remembered talkie role, as the sinister Major Heinrich Strasser in Casablanca (1942). Lastly, Hanna Ralph (Frau Gesellius) was another actor with considerable stage experience. She starred in several films opposite Emil Jannings who she subsequently married, played Queen Brunhilda in Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen (1924) and even played opposite Lionel Barrymore in the Herbert Wilcox directed romantic melodrama Decameron Nights (1924). But with the coming of sound she largely refocused her acting career back on stage work.

So, all in all, Opium for me fell into that category of interesting, watchable but somewhat below par cinema. Its not one I’ll be rushing to see again but did give enough of a taster of director Reinert’s work to make me want to see more of what little of his work that survives, in particular his next major project, Nerves.

So, all in all, Opium for me fell into that category of interesting, watchable but somewhat below par cinema. Its not one I’ll be rushing to see again but did give enough of a taster of director Reinert’s work to make me want to see more of what little of his work that survives, in particular his next major project, Nerves.

Piano accompaniment for the film came from Costas Fotopoulos, who thankfully managed to avoid the melodramatic overload of the film and worked in some interesting Chinese and Indian themes where necessary.

According to Amazon.com Opium has been released on disc but is not currently available. It can be watched on YouTube albeit in a poor quality version with no musical accompaniment or inter-title translations.