Kennington Bioscope at The Cinema Museum, London

1 November 2016

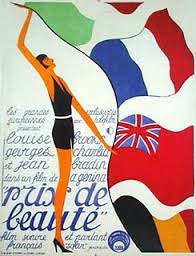

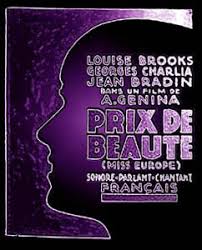

Having barely recovered from the Kennington Bioscope’s superb Silent Laughter Weekend (Click here for a review) it was back to the Cinema Museum tonight for another of the Bioscope’s regular evening events, but one which marked a significant change of mood from their comedy weekend. The main feature tonight was the rarely screened (and possibly first time ever in London?) silent version of the Louise Brooks melodrama Prix de Beaute (1930, image left). But first up there was a presentation on the move from silent to sound film production in Europe.

Having barely recovered from the Kennington Bioscope’s superb Silent Laughter Weekend (Click here for a review) it was back to the Cinema Museum tonight for another of the Bioscope’s regular evening events, but one which marked a significant change of mood from their comedy weekend. The main feature tonight was the rarely screened (and possibly first time ever in London?) silent version of the Louise Brooks melodrama Prix de Beaute (1930, image left). But first up there was a presentation on the move from silent to sound film production in Europe.

Tonight’s guest presenter was Geoff Brown, a film historian at De Montfort University who is involved in a project to study this shift from silent to sound film.  He began by highlighting that at the beginning of this transition period in Europe, it was Britain and specifically the British International Pictures (BIP) production company that was leading

He began by highlighting that at the beginning of this transition period in Europe, it was Britain and specifically the British International Pictures (BIP) production company that was leading  the way in sound film production and screening. Factors accounting for BIP’s pre-eminence probably included; firstly, its relative prosperity meaning it could afford to fund the development and installation of sound equipment; secondly, control of its own cinema chain which could be re-equipped with sound equipment to screen its sound films; and thirdly, its commonality of language with the United States which was leading the way in sound film development. BIP’s industry lead

the way in sound film production and screening. Factors accounting for BIP’s pre-eminence probably included; firstly, its relative prosperity meaning it could afford to fund the development and installation of sound equipment; secondly, control of its own cinema chain which could be re-equipped with sound equipment to screen its sound films; and thirdly, its commonality of language with the United States which was leading the way in sound film development. BIP’s industry lead  was underlined by the fact that French film production companies were coming to Britain by 1929 specifically to make sound films. .

was underlined by the fact that French film production companies were coming to Britain by 1929 specifically to make sound films. .

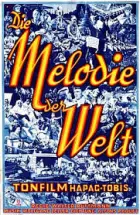

Geoff illustrated his presentation with clips from a number of early sound films including Kitty (Dir. Victor Saville, 1928/9, UK) hailed as a film in which ‘Britain’s premier stars speak the mother tongue’. In fact star Estelle Brody was American and the sound scenes were filmed at a New York studio and the results

film in which ‘Britain’s premier stars speak the mother tongue’. In fact star Estelle Brody was American and the sound scenes were filmed at a New York studio and the results  were fairly crude and stilted. A 1928/9 German film Melodie de Welt (Dir. Walther Ruttman), a documentary on world customs and characteristics had similarly stilted

were fairly crude and stilted. A 1928/9 German film Melodie de Welt (Dir. Walther Ruttman), a documentary on world customs and characteristics had similarly stilted  dialogue, particularly in a clip featuring G B Shaw. But by 1929 things were improving. The British film Atlantic (Dir. E A Dupont), about the sinking of the Titanic, quite effectively conveyed the sound in panicked crowd scenes with shouts and

dialogue, particularly in a clip featuring G B Shaw. But by 1929 things were improving. The British film Atlantic (Dir. E A Dupont), about the sinking of the Titanic, quite effectively conveyed the sound in panicked crowd scenes with shouts and  screaming, a band playing and the noise of lifeboats descending and splashing in the water. In Germany, things were also improving by 1929. Melodie Des Herzens (Dir. Hanns Schwarz) showed a (beautifully shot) comparison between rural and urban landscapes with very effective sounds of rural life and street scenes. It also earned praise from, amongst others, Rene Clair who hailed its understated use of dialogue in contrast to many US films. It was clear how much progress had been made by 1931 with a clip from Czech

screaming, a band playing and the noise of lifeboats descending and splashing in the water. In Germany, things were also improving by 1929. Melodie Des Herzens (Dir. Hanns Schwarz) showed a (beautifully shot) comparison between rural and urban landscapes with very effective sounds of rural life and street scenes. It also earned praise from, amongst others, Rene Clair who hailed its understated use of dialogue in contrast to many US films. It was clear how much progress had been made by 1931 with a clip from Czech  film Ze Soboty Na Nedeli (Dir Gustav Machaty) which had an opening credits jazz score nicely integrated with the visuals while the character dialogue was of a far more naturalistic style. And a final still from 1930 of a large purpose-built sound studios opening in Germany indicated that the British lead in sound film development in Europe was pretty much at an end. This was a really fascinating presentation, well delivered with some excellent film clips which effectively highlighted the progress being made in transition from silent to sound films.

film Ze Soboty Na Nedeli (Dir Gustav Machaty) which had an opening credits jazz score nicely integrated with the visuals while the character dialogue was of a far more naturalistic style. And a final still from 1930 of a large purpose-built sound studios opening in Germany indicated that the British lead in sound film development in Europe was pretty much at an end. This was a really fascinating presentation, well delivered with some excellent film clips which effectively highlighted the progress being made in transition from silent to sound films.

Then it was time for the main feature. I had not previously seen either the sound or silent version of Prix de Beaute (Dir. Augusto Genina, 1930) but anything starring Louise Brooks deserves a look. Here she plays Lucienne Garnier, an office typist who enters a beauty contest. When her jealous fiancé Andre (Georges Chalia) expresses his contempt for beauty contests she tries to withdraw but it is too late and she wins. Unbeknownst to Andre she now leaves Paris by train for Spain where she is entered in the Miss Europe contest. When Andre finds out he follows. By the time he arrives she has won the contest and is being courted by various rich socialites including a turbaned Indian prince (Yves Glad) and the Russian Prince Grabovsky (Jean Bradin). Andre gives her an ultimatum, return home with him or they are through. Despite Grabovsky’s prediction that ‘she can’t make Andre happy and won’t be happy herself’ she leaves with Andre. But having experienced the highs of fame she now finds domestic life in Paris dull and tedious. The reappearance of Grabovsky with the offer of a movie contract proves tempting although she eventually tears this up. But a visit with Andre to a working class funfair and a posed

Then it was time for the main feature. I had not previously seen either the sound or silent version of Prix de Beaute (Dir. Augusto Genina, 1930) but anything starring Louise Brooks deserves a look. Here she plays Lucienne Garnier, an office typist who enters a beauty contest. When her jealous fiancé Andre (Georges Chalia) expresses his contempt for beauty contests she tries to withdraw but it is too late and she wins. Unbeknownst to Andre she now leaves Paris by train for Spain where she is entered in the Miss Europe contest. When Andre finds out he follows. By the time he arrives she has won the contest and is being courted by various rich socialites including a turbaned Indian prince (Yves Glad) and the Russian Prince Grabovsky (Jean Bradin). Andre gives her an ultimatum, return home with him or they are through. Despite Grabovsky’s prediction that ‘she can’t make Andre happy and won’t be happy herself’ she leaves with Andre. But having experienced the highs of fame she now finds domestic life in Paris dull and tedious. The reappearance of Grabovsky with the offer of a movie contract proves tempting although she eventually tears this up. But a visit with Andre to a working class funfair and a posed  husband-and-wife picture in a photo-booth convinces her that this is no longer the life for her. The next morning Andre finds a letter saying she has gone. Racked with jealousy he eventually tracks her down to a studio where she is viewing her successful screen test with the movie executives and he shoots her dead.

husband-and-wife picture in a photo-booth convinces her that this is no longer the life for her. The next morning Andre finds a letter saying she has gone. Racked with jealousy he eventually tracks her down to a studio where she is viewing her successful screen test with the movie executives and he shoots her dead.

Brooks had already left Hollywood once for Europe when Paramount refused to increase her salary after completing The Canary Murder Case (Dir. Mal St Clair, 1928). In Berlin she starred in Pandora’s Box (Dir. G W Pabst, 1929) before returning once more to America where Paramount now wanted her to add dialogue to The Canary Murder Case which was being converted to a sound film. Despite their generous financial offers she refused, leaving instead for Paris after Pabst suggested she make a film (Prix de Beaute) written especially  for her and directed by Rene Clair. While waiting for this project to get off the ground she starred in Pabst’s Diary of a Lost Girl (1929), by which time Italian expatriate Augusto Genina had taken over as director of Prix de Beaute. Although shooting apparently went smoothly Brooks’ heavy drinking appeared to cause some

for her and directed by Rene Clair. While waiting for this project to get off the ground she starred in Pabst’s Diary of a Lost Girl (1929), by which time Italian expatriate Augusto Genina had taken over as director of Prix de Beaute. Although shooting apparently went smoothly Brooks’ heavy drinking appeared to cause some consternation, with Genina reportedly recalling that Brooks would be propped up in a chair each morning and her make-up applied while still asleep.

consternation, with Genina reportedly recalling that Brooks would be propped up in a chair each morning and her make-up applied while still asleep.

Originally scripted as a silent, it was subsequently decided to shoot Prix de Beaute as a sound film, apparently in French, Italian, German and English versions. But on its release the film’s poor sound effects and dubbed dialogue were already seen as out-moded and the film flopped in Europe and never got a US release. However, a silent version of the film exists, restored by Cineteca di Bologna  from an incomplete silent print held by Cineteca Italiana and using muted portions of the sound print held by Cinémathèque Française, and this is the one we watched this evening.

from an incomplete silent print held by Cineteca Italiana and using muted portions of the sound print held by Cinémathèque Française, and this is the one we watched this evening.

Not surprisingly, given that Prix de Beaute was written specifically for her, the film revolves around Louise Brooks’ portrayal of Lucienne. But there are two very different sides to Brooks’ character on show here. In the first half of the film she is the bubbly, effervescent typist dreaming of and then finding fame. Unlike her more angst ridden personas in Pandora’s Box and Diary of a Lost Girl here she is high spirited and carefree, her smile lighting up the screen as she effectively portrays a woman basking in the limelight her success has created. But the second half sees a darker side to her character when, having returned to domestic drudgery in Paris, she expresses with consummate skill the inner turmoil she faces between love for her fiancé and desire for the highlife she has now had a  taste of. While the caged bird symbolism may nowadays be seen as something of a cliché this could well have been the first time it was used on film. The scenes at the funfair are particularly poignant as Brooks, looking at the rough and coarse characters surrounding her and tiring of her fiancé’s macho posturing, beautifully conveys the realisation that she has made the wrong choice and is now trapped in a life she no longer wants.

taste of. While the caged bird symbolism may nowadays be seen as something of a cliché this could well have been the first time it was used on film. The scenes at the funfair are particularly poignant as Brooks, looking at the rough and coarse characters surrounding her and tiring of her fiancé’s macho posturing, beautifully conveys the realisation that she has made the wrong choice and is now trapped in a life she no longer wants.

And this is not a film in which any of the male characters engender much sympathy. Georges Charlia effectively portrays Andre as the jealous, controlling, macho man, resentful of anyattention paid to his fiancé whose place he sees very much as being in  the home. Jean Bradin as Grabovsky is equally controlling but in a subtler way (reminiscent of George Sanders at his suave and slimiest peak) whilst Yves Glad as the Maharajah as a vapid smooth talker.

the home. Jean Bradin as Grabovsky is equally controlling but in a subtler way (reminiscent of George Sanders at his suave and slimiest peak) whilst Yves Glad as the Maharajah as a vapid smooth talker.

While the film realistically portrays the social pressure on women at that time, it is also surprisingly modern in depicting the path Lucienne eventually chooses. Most other films of the era would have her ‘coming to her senses’ and realising that home life is what she wants after all. In particular, I thought back to seeing Betty Balfour in Paradise (Dir. Denison Clift, 1928) ( shown earlier this year at the KenBio) whose sojourn to the south of

France comes to an end when her fiancé arrives ‘to take her home’ and she meekly agrees. This is not the route for Lucienne but there is an air of inevitability that she will pay a heavy price for her choice.

Also of particular note is the film’s superb cinematography by Louis Nee and Rudolph Mate (the latter going on to film Foreign Correspondent (1940), Gilda (1946) and Lady From Shanghai (1947) amongst many others). While the beauty pageant scenes have an almost documentary feel to them the Parisian street scenes beautifully portray the hustle and bustle of the city. The shots of the newspaper machinery would do justice to Vertov while the closing scene of Lucienne’s movie image projecting on to her dying face is stunning.

them the Parisian street scenes beautifully portray the hustle and bustle of the city. The shots of the newspaper machinery would do justice to Vertov while the closing scene of Lucienne’s movie image projecting on to her dying face is stunning.

With none of Brooks’ European films receiving either critical or popular success on their initial release she returned to America. But little work was forthcoming, although her independent spirit didn’t help, apparently turning down a role opposite James Cagney in The Public Enemy (1931)  because she ‘hated Hollywood’. She made her last film in 1938 before going on to a string of mundane jobs including a dancer and salesgirl in a department store. It was only with the critical rediscovery of her silent films in the late 1950s and 1960s that her reputation was resurrected and she eventually achieved considerable success as a noted writer in her own right. Brooks died in 1985 of a heart attack aged 75.

because she ‘hated Hollywood’. She made her last film in 1938 before going on to a string of mundane jobs including a dancer and salesgirl in a department store. It was only with the critical rediscovery of her silent films in the late 1950s and 1960s that her reputation was resurrected and she eventually achieved considerable success as a noted writer in her own right. Brooks died in 1985 of a heart attack aged 75.

Lastly, praise must go to accompanist Stephen Horne for a superlative live score on piano, accordion and flute (often played simultaneously, although I’m still not sure how he manages this!) which added an extra emotional depth to the film and beautifully captured both the highs and lows. In particular, I loved his take on the on-screen pianola, which sounded great. Additionally, I’m not sure who’s idea it was to add the voice (albeit dubbed) of Lucienne singing at the film’s climax but this was a masterstroke. Loved it!

(Prix de Beaute is obtainable on DVD from KinoVideo with just a few short clips available on line.)