Kennington Bioscope at The Cinema Museum, London

5 December 2018

(Warning: Spoilers Throughout)

There was a vaguely end-of-term feeling this evening at the Kennington Bioscope, what with this being their last event of the year. But as always with the KenBio, the emphasis was on the little-known and the rarely screened. And tonight’s films certainly fell into both of these categories. The main feature was The Virgin of Stamboul (1920), starring Priscilla Dean and Wallace Beery. But

There was a vaguely end-of-term feeling this evening at the Kennington Bioscope, what with this being their last event of the year. But as always with the KenBio, the emphasis was on the little-known and the rarely screened. And tonight’s films certainly fell into both of these categories. The main feature was The Virgin of Stamboul (1920), starring Priscilla Dean and Wallace Beery. But  first up was a real British rarity, the true-life crime melodrama Maria Marten (1928).

first up was a real British rarity, the true-life crime melodrama Maria Marten (1928).

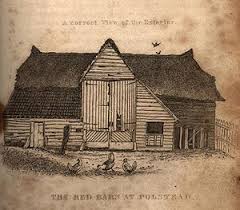

In the film, the title character (Trilby Clark) is the daughter of poor farm workers and infatuated with William Corder (Wallace Ward), the local squire. Corder is something of a womaniser and one evening is confronted by the father and brother of a local gypsy girl who claims that Corder has said he will marry her. Corder denies the charge and in a subsequent argument shoots the father dead. On hearing the news the gypsy girl commits suicide while her brother, Carlos (James Knight), swears revenge. Corden and Marten embark upon an affair, meeting secretly at the Red Barn. But when Maria talks of marriage, Corden says he will set a date upon his return from business in London. However, in London he courts a wealthy heiress and they agree to marry, with Corden already planning to use her dowry to pay off his debts.

Back in the village, in Corden’s continued absence Maria confesses to her parents that she is pregnant. But at that moment Corden returns and says he will marry her. However, to avoid scandal they will have to secretly leave the village under cover of darkness and they agree to meet the following evening at the Red Barn before making their escape. But as Maria makes her way to the barn, Corden is already there digging a grave. When she arrives he shoots her, buries the body and leaves. Maria’s family,  worried at the lack of news from her, ask her brother in law to check up on her at Cordon’s London house. But the Mrs Corden he finds is the rich heiress rather than Maria. On learning the news, Maria’s mother becomes hysterical and reveals her dream that Maria is buried in the Red Barn. Upon the discovery of her body, the gypsy Carlos, who is now a legal officer, tracks down Cordon, who is arrested and subsequently hanged.

worried at the lack of news from her, ask her brother in law to check up on her at Cordon’s London house. But the Mrs Corden he finds is the rich heiress rather than Maria. On learning the news, Maria’s mother becomes hysterical and reveals her dream that Maria is buried in the Red Barn. Upon the discovery of her body, the gypsy Carlos, who is now a legal officer, tracks down Cordon, who is arrested and subsequently hanged.

Introducing the screening, film historian Michael Pointon provided some (at times gruesome) background to the real life 1827 Suffolk murder case on which the film was based. Although the film is set (based upon its regency style costumes) some fifty years earlier than the real life murder (causing Michael to ponder that the studio perhaps sought to re-use costumes made for another film as an economy measure) the story it tells is broadly true to life. The actual murder attracted great popular interest at the time. It is variously claimed that between seven and twenty thousand people watched Corden’s execution. The hangman’s rope was reportedly auctioned off for a guinea a foot, Corden’s body was dissected by medical students and part of his skin was tanned and used to bind a book on the murder (I did say it was gruesome!). So it is perhaps not surprising that the story was seen as eminently suitable source material right from the earliest days of the film industry, with four silent adaptions known to have been made. Those from 1902 (Dir. Dicky Winslow), 1908 (Dir. Willim Hagger) and 1913 (Dir. Maurice Elvey) are sadly now all considered lost.

But what of this evening’s 1928 version. Well, its not a classic! In fact it had a bit of the look of a ‘quota quickie’. Michael Pointon in his introduction had already mentioned the possibility of the costumes being re-used from an earlier film and in one shot, a supposedly solid stone wall was clearly billowing as a draft caught the painted cloth backdrop, so the production values were not exactly ‘big budget’. But although the Cinematograph Films Act and its quotas was passed in 1927 it did not come into force until April of the following year, a month after the release of Maria Marten, so the film is just a little too early to be a product of this legislation. Although the film tells a cogent story, its progression is somewhat plodding and ponderous with no real build up of tension. Additionally, the sub-plot of Carlos the Gypsy’s search for revenge doesn’t add a great deal. Although the cinematography was nondescript, there was one lovely scene as Corden guiltily emerges from the barn having shot Maria and the shadow of a dangling rope passes in front of his  face in the shape of a hangman’s noose. However, there is a similarly effective scene in Raoul Walsh’s 1915 crime drama Regeneration (1915), so this wasn’t exactly original.

face in the shape of a hangman’s noose. However, there is a similarly effective scene in Raoul Walsh’s 1915 crime drama Regeneration (1915), so this wasn’t exactly original.

Amongst the stars, Trilby Clark (image, right) played Maria without any undue theatrics. Clark was born in Australia and made at least one film in her native country before traveling to America where she made around a dozen further films including the intriguingly titled Catherine Bennett Throws Missiles (1926) before moving on to Britain, where Maria Marten was her second film. Her last recorded film was in 1930 after which nothing more is known other than her death in 1983. Warrick Ward (image, left) was a little more effective as the  somewhat cold and detached Corden. Ward appeared in films throughout the 1920s, in Britain, Europe and America. His acting high-point was probably that of the trapeze artist Artinelli in E A Dupont’s Variety (1925), competing with Emil Jennings for the affections of Lya de Putti. He appeared alongside de Putti again in The Informer (Dir. Arthur Robinson, 1929) and acted with Brigitte Helm in The Wonderful Lies of Nina Petrovna (Dir. Arthur Schwarz, 1929). There

somewhat cold and detached Corden. Ward appeared in films throughout the 1920s, in Britain, Europe and America. His acting high-point was probably that of the trapeze artist Artinelli in E A Dupont’s Variety (1925), competing with Emil Jennings for the affections of Lya de Putti. He appeared alongside de Putti again in The Informer (Dir. Arthur Robinson, 1929) and acted with Brigitte Helm in The Wonderful Lies of Nina Petrovna (Dir. Arthur Schwarz, 1929). There  was also a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it appearance by Chili Bouchier (image, right) in an early acting role. She would go on to much greater things with a string of successful starring roles and was often hailed as ‘Britain’s first female sex symbol’ or Britain’s answer to Clara Bow.

was also a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it appearance by Chili Bouchier (image, right) in an early acting role. She would go on to much greater things with a string of successful starring roles and was often hailed as ‘Britain’s first female sex symbol’ or Britain’s answer to Clara Bow.

Director Walter West had emerged during the 1910s as one of Britain’s premier producer/directors but by the time of Maria Marten his career was well past its best. The company he founded for this film, QTS Productions, made just one other picture, Sweeney Todd (Dir. Walter West, 1928) before folding.

Providing live piano accompaniment and helping make a poor film watchable was the ever reliable John Sweeney.

There is no sign of Maria Marten being available on disc or on-line (in fact, several sources list it as a ‘lost film’!). .

It was then time for the main feature, The Virgin of Stamboul (Dir. Tod Browning, US, 1920). In his introduction, film historian Kevin Brownlow spoke fondly of meeting actress Priscilla Dean and of her reminiscences of working with the often somewhat unconventional director Tod Browning.

It was then time for the main feature, The Virgin of Stamboul (Dir. Tod Browning, US, 1920). In his introduction, film historian Kevin Brownlow spoke fondly of meeting actress Priscilla Dean and of her reminiscences of working with the often somewhat unconventional director Tod Browning.

The film opens with penniless Sari (Priscilla Dean) begging on the streets of Stamboul (Istanbul). In the Arabian desert, expat American Captain. Carlisle Pemberton (Wheeler Oakman) is bidding farewell to the men of the crime fighting Black Horse Cavalry before he sets off to visit the city. Once in Stamboul, Pemberton meets and is infatuated with Sari. Also  arriving in Stamboul from the desert is Sheik Ahmed Hamid (Wallace Beery), with plans to visit his harem and in particular his favourite wife Resha (Ethel Ritchie). But he discovers Resha with another man. Following him to a mosque Hamid stabs his rival to death. But Hamid’s crime is witnessed by Sari. He first tries to silence Sari by enticing her into his harem but when she refuses he sets out to buy her from her mother and take her as his bride. When Pemberton discovers Hamid’s plan he bribes Hamid’s representative so that at the proxy wedding it is he that is married to Sari rather than Hamid. On discovering the deception Hamid kidnaps both Pemberton and Sari, imprisoning them in his desert fortress. Sari manages to escape and rides for help to the Black Horse Cavalry. As they storm the fort, Pemberton and Hamid fight and the sheik is killed. Sari and Pemberton are reunited.

arriving in Stamboul from the desert is Sheik Ahmed Hamid (Wallace Beery), with plans to visit his harem and in particular his favourite wife Resha (Ethel Ritchie). But he discovers Resha with another man. Following him to a mosque Hamid stabs his rival to death. But Hamid’s crime is witnessed by Sari. He first tries to silence Sari by enticing her into his harem but when she refuses he sets out to buy her from her mother and take her as his bride. When Pemberton discovers Hamid’s plan he bribes Hamid’s representative so that at the proxy wedding it is he that is married to Sari rather than Hamid. On discovering the deception Hamid kidnaps both Pemberton and Sari, imprisoning them in his desert fortress. Sari manages to escape and rides for help to the Black Horse Cavalry. As they storm the fort, Pemberton and Hamid fight and the sheik is killed. Sari and Pemberton are reunited.

The story for the Virgin of Stamboul came from successful scenario writer H H van Loan. In his book ‘The Parade’s Gone By’, Kevin Brownlow quotes from Loan’s biography, titled in a somewhat does-what-it-says-on-the-tin fashion as ‘How I Did It’, as to what makes a successful scenario writer, “First, establish a reason for your story, then introduce the characters, and after you’ve done that, make a dash for the climax. That’s all there is to it. Establish a premise and then rush for the final scene. Don’t waste any time on route. Be sure that it contains action, action, and then some more action.” Simples!! And that’s really what we got, a cogent plot, three central characters and an all action  finale. So where did it all go so wrong. Well, to start with there was the casting and performance of Priscilla Dean (image, left) Bubbly effervescence really didn’t sit comfortably here and the already

finale. So where did it all go so wrong. Well, to start with there was the casting and performance of Priscilla Dean (image, left) Bubbly effervescence really didn’t sit comfortably here and the already  twice married Dean (acting here opposite her then husband Wheeler Oakman (image, right, together)) hardly met the requirements of the film’s title! Then there was her dramatic transformation from beggar girl to action hero, her dramatic escape from Hamid’s fort, crack shot with a rifle, heroically scaling the castle walls and really putting the boot in to anyone who got in her way (did that poor tribesman really deserve a third kick in the groin!!?). Oakman himself was a little more convincing as Pemberton while the always over the top

twice married Dean (acting here opposite her then husband Wheeler Oakman (image, right, together)) hardly met the requirements of the film’s title! Then there was her dramatic transformation from beggar girl to action hero, her dramatic escape from Hamid’s fort, crack shot with a rifle, heroically scaling the castle walls and really putting the boot in to anyone who got in her way (did that poor tribesman really deserve a third kick in the groin!!?). Oakman himself was a little more convincing as Pemberton while the always over the top  but ever reliable baddie of any nationality, Wallace Beery (image, right), just did what he usually did as Sheik Ahmed. As the film progressed it turned from romantic melodrama to western with the Seventh, whoops, I mean Black Horse Cavalry riding to the rescue. And then there was the somewhat disconcerting impression given that the Arabian desert began about ten yards from the gates of Stamboul.

but ever reliable baddie of any nationality, Wallace Beery (image, right), just did what he usually did as Sheik Ahmed. As the film progressed it turned from romantic melodrama to western with the Seventh, whoops, I mean Black Horse Cavalry riding to the rescue. And then there was the somewhat disconcerting impression given that the Arabian desert began about ten yards from the gates of Stamboul.

By director Tod Browning (image, left)’s standards, the film was fairly conventional (unless you count Sari feeding the local pigeons from her mouth or the Sheik presenting Resha with a knife stained with the blood of her dead lover!). There was little sign here of the weirdness to come with the transvestite ventriloquist of The Unholy Three (1925), the armless knife thrower of The Unknown (1927) or the veritable army of oddities in Freaks (1932).

By director Tod Browning (image, left)’s standards, the film was fairly conventional (unless you count Sari feeding the local pigeons from her mouth or the Sheik presenting Resha with a knife stained with the blood of her dead lover!). There was little sign here of the weirdness to come with the transvestite ventriloquist of The Unholy Three (1925), the armless knife thrower of The Unknown (1927) or the veritable army of oddities in Freaks (1932).

It was down to Cyrus Gabrysch’s live piano accompaniment to make this a more meaningful experience, a job he did superbly.

The Virgin of Stamboul is available on DVD from the Silent Gems Collection.

And that was it, the conclusion of the Kennington Bioscope’s 2018 season. Perhaps it wasn’t the strongest programme on which to finish but that’s not what the KenBio is about. Their raison d’être isn’t to screen the likes of mainstream classics such as Metropolis or Caligari or The General, good as these films are. No, the KenBio is there to screen the sort of films you are unlikely to see anywhere else, the rarities and rarely screened and in this you sometimes have to take the rough with the smooth. But all in all they have had a tremendously successful year. Screenings of rarities such as The Bride of Glomdal (aka Glomdalsbruden) (Dir. Carl Theodor Dreyer. Nor., 1926), Miss Lulu Bett (Dir. William C De Mille, US, 1921), The Golden Butterfly (Dir. Michael Curtiz, Aust-Ger, 1926) and Au Bonheur des Dames (Dir. Julien Duvivier, Fr, 1930) will long live in the memory and their Silent Guns Day featuring films focused upon the First World war was one of the best days of silent film I’ve experienced in a long while. Lets hope they keep up the good work in 2019.

Provisional new year screening dates are 9th and 30th January, 6th February and 13th March. Don’t miss them.