The Theatreship, Canary Wharf

7th February 2026

(Warning: spoilers throughout)

There is always that extra frisson of anticipation when I’m heading to a silent film screening at a venue I’ve never been to before. And, as I crossed the footbridge over South Quay at Canary Wharf it was clear that this evening’s venue promised to be something out of the ordinary. My destination was the Theatreship, moored in Millwall Cutting. Built in 1913, the Theatreship started out as a general cargo vessel transporting bulk dry cargoes but has now been converted into an arts centre with a 100 seat auditorium.

There is always that extra frisson of anticipation when I’m heading to a silent film screening at a venue I’ve never been to before. And, as I crossed the footbridge over South Quay at Canary Wharf it was clear that this evening’s venue promised to be something out of the ordinary. My destination was the Theatreship, moored in Millwall Cutting. Built in 1913, the Theatreship started out as a general cargo vessel transporting bulk dry cargoes but has now been converted into an arts centre with a 100 seat auditorium.

And the film I was going to see at the Theatreship? This was even older than the ship itself. L’Inferno, directed by Francesco Bertolini, Adolfo Padovan and Giuseppe de Liguoro, was released in 1911, the first feature length film to be made in Italy and only the second in the world.

And the film I was going to see at the Theatreship? This was even older than the ship itself. L’Inferno, directed by Francesco Bertolini, Adolfo Padovan and Giuseppe de Liguoro, was released in 1911, the first feature length film to be made in Italy and only the second in the world.

L’Inferno was based on the first part of the fourteenth-century epic La Divina Commedia by Italian poet Dante Alighieri depicting the journey Dante takes through Hell, as he strays from righteousness and discovers sin. The film opens with Dante (played by Salvatore Papa) lost in a dark  and gloomy wood, seeking to climb the hill of salvation. His way is blocked by three wild beasts, representing avarice, pride and lust. Beatrice, Dante’s ideal of womanhood descends from paradise and asks Virgil (Arturo Pirovano), a pious poet, to rescue and guide Dante. He does so and bids Dante to follow him into the portals of the Inferno, abandoning all hope as he enters. At the River Acheron they encounter Charon who ferries the souls of the dead. Charon carries them across the river and they arrive at the first of Dante’s infamous nine levels of hell, limbo, the punishment for those not baptised who are prevented from reaching heaven and live out an existence without hope. Next they

and gloomy wood, seeking to climb the hill of salvation. His way is blocked by three wild beasts, representing avarice, pride and lust. Beatrice, Dante’s ideal of womanhood descends from paradise and asks Virgil (Arturo Pirovano), a pious poet, to rescue and guide Dante. He does so and bids Dante to follow him into the portals of the Inferno, abandoning all hope as he enters. At the River Acheron they encounter Charon who ferries the souls of the dead. Charon carries them across the river and they arrive at the first of Dante’s infamous nine levels of hell, limbo, the punishment for those not baptised who are prevented from reaching heaven and live out an existence without hope. Next they  encounter the punishment of the carnal sinners, who are endlessly blown by every gust of wind from hell. Amongst those cast upon the winds for eternity are Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta, who had who had an adulterous affair, which is shown in flashback.

encounter the punishment of the carnal sinners, who are endlessly blown by every gust of wind from hell. Amongst those cast upon the winds for eternity are Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta, who had who had an adulterous affair, which is shown in flashback.

At the next level, the circle of the Gluttons, Dante and Virgil’s way is blocked by the three-headed monster Cerberus. But he is appeased by Virgil throwing a handful of earth in his mouth. The Gluttons are tortured by eternal rain as they lie prostate on the ground. Our travelers then encounter Pluto, on guard over misers and spendthrifts. He is enraged at the sight of Dante but powerless to harm him. The misers and spendthrifts are condemned to roll  great bags of money around their circle of the Inferno. Next, Dante reaches the Stygian Swamp where the slothful and wrathful are immersed, forever to fight amongst themselves. To reach the city of Dis, the atheist Phleguyas ferries Dante and Virgil across the swamp. Entry to the city is initially barred by a horde of evil spirits and three furies but an angel appears and commands the gates be opened. Inside, they encounter the heretics who suffer the punishment of eternal burial in pits of fire. The next level of punishment is that of suicides, who are changed into shrunken and gnarled trees on which Harpies stand watch and pluck at the trees inflicting everlasting pain on the

great bags of money around their circle of the Inferno. Next, Dante reaches the Stygian Swamp where the slothful and wrathful are immersed, forever to fight amongst themselves. To reach the city of Dis, the atheist Phleguyas ferries Dante and Virgil across the swamp. Entry to the city is initially barred by a horde of evil spirits and three furies but an angel appears and commands the gates be opened. Inside, they encounter the heretics who suffer the punishment of eternal burial in pits of fire. The next level of punishment is that of suicides, who are changed into shrunken and gnarled trees on which Harpies stand watch and pluck at the trees inflicting everlasting pain on the  souls trapped within them. Another flashback concerns Peter of Vigna, punished for treason by being blinded, after which he dashes out his own brains on the dungeon floor. Moving on to blasphemers, they are stricken by a rain of fire eternally falling upon them.

souls trapped within them. Another flashback concerns Peter of Vigna, punished for treason by being blinded, after which he dashes out his own brains on the dungeon floor. Moving on to blasphemers, they are stricken by a rain of fire eternally falling upon them.

Dante and Virgil descend to the next level on the back of the monster Geryon where they encounter souls lashed endlessly by demons; thence to the river of filth in which flatterers and dissolutes are immersed and who seek in vain to wash themselves clean; where those who have sold the church’s goods for gain are tortured by fire on the soles of their feet; and where those who have misappropriated the  property of others are hurled into a river of boiling pitch. Chased by demons Dante and Virgil descend to the next level where hypocrites are forced to wear heavy capes of lead, where robbers are bitten by horrible serpents, where grafters and faithless custodians are changed into disgusting shapes of

property of others are hurled into a river of boiling pitch. Chased by demons Dante and Virgil descend to the next level where hypocrites are forced to wear heavy capes of lead, where robbers are bitten by horrible serpents, where grafters and faithless custodians are changed into disgusting shapes of  animals and where the sowers of discord are maimed by demons.

animals and where the sowers of discord are maimed by demons.

Carried by the giant Antaeus to the next level, where traitors are immersed in a lake of ice and where a Count gnaws on the skull of an Archbishop who ordered the starvation of  the Count and his family; the travelers at last meet the arch traitor Lucifer with his three mouths, chewing on the bodies of Brutus and Cassius. But when all looks lost, Dante and Virgil journey underground to leave Hell and again behold the stars. The film ends with a shot of the Monument to Dante in Trento.

the Count and his family; the travelers at last meet the arch traitor Lucifer with his three mouths, chewing on the bodies of Brutus and Cassius. But when all looks lost, Dante and Virgil journey underground to leave Hell and again behold the stars. The film ends with a shot of the Monument to Dante in Trento.

L’Inferno’s very first screening was at the Teatro Mercadante in Naples on 10 March 1911 but it had a long gestation period having taken Milano Films over three years to produce. As originally released the film reportedly ran well in excess of of two hours. (In her diary Nancy

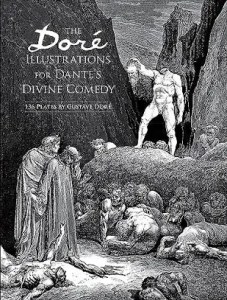

L’Inferno’s very first screening was at the Teatro Mercadante in Naples on 10 March 1911 but it had a long gestation period having taken Milano Films over three years to produce. As originally released the film reportedly ran well in excess of of two hours. (In her diary Nancy  Mitford recorded seeing the film in Italy in 1922, referring to it as Dante, and recorded that it lasted from 9 until 12:15 including two intermissions.) But all that remains today is a 73 minute version. The film’s style is heavily based upon the popular nineteenth-century illustrations produced by Gustave Doré for an 1861 folio edition of La Divina Commedia. L’Inferno was a major commercial success on its release, not just in Italy but also internationally, taking a reported $2 million on its US release alone

Mitford recorded seeing the film in Italy in 1922, referring to it as Dante, and recorded that it lasted from 9 until 12:15 including two intermissions.) But all that remains today is a 73 minute version. The film’s style is heavily based upon the popular nineteenth-century illustrations produced by Gustave Doré for an 1861 folio edition of La Divina Commedia. L’Inferno was a major commercial success on its release, not just in Italy but also internationally, taking a reported $2 million on its US release alone

But watching L’Inferno today, 115 years after its first release, how does the film hold up? OK, some of the special effects may be a little crude and rudimentary, particularly to a modern audience brought up on state of the art CGI, but overall the film still packs a considerable punch. A lot of the imagery remains breathtaking, in particular the heretics buried in pits of fire, blasphemers stricken by a rain of fire, traitors immersed in a lake of ice or the thieves hurled into a river of boiling pitch. Red or blue tinting was well used to enhance the impression of heat or cold. Although a little wobbly some of the matte work was very effective, as was the use of forced perspective in portraying the giants and the multiple exposure work, particularly when depicting the carnal sinners endlessly blown in the wind.

But watching L’Inferno today, 115 years after its first release, how does the film hold up? OK, some of the special effects may be a little crude and rudimentary, particularly to a modern audience brought up on state of the art CGI, but overall the film still packs a considerable punch. A lot of the imagery remains breathtaking, in particular the heretics buried in pits of fire, blasphemers stricken by a rain of fire, traitors immersed in a lake of ice or the thieves hurled into a river of boiling pitch. Red or blue tinting was well used to enhance the impression of heat or cold. Although a little wobbly some of the matte work was very effective, as was the use of forced perspective in portraying the giants and the multiple exposure work, particularly when depicting the carnal sinners endlessly blown in the wind.

But beyond its individual components, the significance of L’Inferno in terms of cinematic history rests as much upon its grand scale, its high production values, its large cast and its  overall mise en scène. At a time when film production worldwide was dominated by 10 or 15 minute shorts, usually made on a shoe-string budget and completed in a couple of days. L’Inferno marked a huge step forward in cinematic style, in effect the birth of the epic. It was somewhat surprising that this transformation came from Italy. The country’s film industry lagged behind that of the US and other European states. The Milano Film production company itself was only formed in 1908. It remains unclear precisely what the impetus behind this move to more epic scale Italian productions was, but there was already an Italian trend towards films of epic potential (if not yet quite realised) such as Nero or the Fall of Rome (1909), Agrippina (1911) and The Fall of Troy (1911). Indeed, the three directors of L’Inferno also made a feature-length

overall mise en scène. At a time when film production worldwide was dominated by 10 or 15 minute shorts, usually made on a shoe-string budget and completed in a couple of days. L’Inferno marked a huge step forward in cinematic style, in effect the birth of the epic. It was somewhat surprising that this transformation came from Italy. The country’s film industry lagged behind that of the US and other European states. The Milano Film production company itself was only formed in 1908. It remains unclear precisely what the impetus behind this move to more epic scale Italian productions was, but there was already an Italian trend towards films of epic potential (if not yet quite realised) such as Nero or the Fall of Rome (1909), Agrippina (1911) and The Fall of Troy (1911). Indeed, the three directors of L’Inferno also made a feature-length  adaptation of Homer’s Odyssey the same year. The success of L’Inferno would pave the way for ever bigger and spectacular Italian productions including The Last Days of Pompeii (1913) with its dramatic special effects, Quo Vadis (1913) with its cast of thousands and lavish set design, culminating finally in the release of Cabiria (1914) made on a truly epic scale and now considered the summit of Italian silent film production.

adaptation of Homer’s Odyssey the same year. The success of L’Inferno would pave the way for ever bigger and spectacular Italian productions including The Last Days of Pompeii (1913) with its dramatic special effects, Quo Vadis (1913) with its cast of thousands and lavish set design, culminating finally in the release of Cabiria (1914) made on a truly epic scale and now considered the summit of Italian silent film production.

Yet despite its ground breaking reputation, L’Inferno was already a somewhat old fashioned film even at the time of its initial release. The film is primarily a collection of tableaux with only a loose narrative structure. These are almost invariably filmed in a single take, in long-shot view, using a fixed camera. There are no close-up scenes and no proper cross-cutting editing, techniques which were already in regular use by other film makers. Additionally, the use of wordy  inter-titles to describe the events of the next scene was already becoming out-dated. And while the acting style may have been characteristic of the era it now seems enormously over-theatrical, little more than a collection of grand gestures. But one striking element of the film which was a long way ahead of its time was the level of (largely male) nudity amongst the cast. This is particularly surprising in a film of this vintage, especially one made in a conservative Catholic country. But it was in line with Dore’s illustrations and the Catholic church could hardly complain when the film was such a strident warning of the consequences of sin!

inter-titles to describe the events of the next scene was already becoming out-dated. And while the acting style may have been characteristic of the era it now seems enormously over-theatrical, little more than a collection of grand gestures. But one striking element of the film which was a long way ahead of its time was the level of (largely male) nudity amongst the cast. This is particularly surprising in a film of this vintage, especially one made in a conservative Catholic country. But it was in line with Dore’s illustrations and the Catholic church could hardly complain when the film was such a strident warning of the consequences of sin!

Nevertheless, L’Inferno remains a key film in the development of cinematic form. In the words of silent film enthuisiast and blogger Paul Joyce; “It’s an uncanny masterpiece with lots of weirdly-memorable imagery – an unsettling mix of late middle-ages religious sensibilities with early twentieth century experimentation: Méliès meets Hieronymous Bosch.” And as such, its not to be missed.

But this evening wasn’t just about the film. What about the musical accompaniment? This came from a trio of very talented musicians, Ignacio Salvadores , a multi-instrumentalist from Buenos Aires based in London since 2016, Nyssa, a Canadian songwriter, vocalist and flautist, and Al Robinson, a British multi-instrumentalist and songwriter. Their choice of L’Inferno was a brave one given that the film is so little known and its subject matter one of almost unrelenting gloom. And with musicians largely new to silent film scoring there is always the risk that they would see the film as simply a backdrop to their music. But there was no need to worry here. Using a variety of saxophones, bass guitar, flute, whistle, percussion and vocals, seamlessly mixed together, they crafted a score which was perfectly in sync with the visuals of the film and complemented it beautifully. Having come up with an overall structure for their accompaniment, the trio were not working from a written score, but largely improvising on the evening. At times ethereal and at other times almost discordant and perfectly reflecting the on screen descent into hell and eventual salvation, the accompaniment took the film to a new level and served to make the evening a particular success. This is a silent film and accompaniment that deserves to be seen and heard by a wider audience and I will certainly be looking out for any further silent films accompanied by these three musicians.

This screening of L’Inferno is part of a Silent Film with New Sound season at Theatreship. Future screenings will include Metropolis, Battleship Potemkin and Man With A Movie Camera. Details of these screenings can be found here or on the live events listing page of silentfilmcalendar.org.