It’s that time of the year again when we look back over the last 12 months of silent film viewing, to highlight a few trends, pick out some of the highs (and lows!) and come up with our favourite silent film events of the year.

Film Listings

With just 402 screenings, 2023 saw the lowest number of individual silent film events since we started our annual reviews back in 2016. It was, therefore, going to be interesting to see whether this decline continued in 2024 or if the number of silent film screenings bounced back. In the event, nothing changed, because in 2024 we recorded 402 screenings, exactly the same number as the previous year!!

With just 402 screenings, 2023 saw the lowest number of individual silent film events since we started our annual reviews back in 2016. It was, therefore, going to be interesting to see whether this decline continued in 2024 or if the number of silent film screenings bounced back. In the event, nothing changed, because in 2024 we recorded 402 screenings, exactly the same number as the previous year!!

Looking at the numbers of films screened, it was good to see that the total number of different titles screened has gone up since last year and now stands at 174. This is not far short of the 187 different films screened in 2022, despite there being over a hundred more films in total screened in that year compared to 2024. This is hopefully a further sign that film programmers are perhaps becoming just a little bit more adventurous and less wedded to screening the somewhat over used old favourites.

But the biggest changes in films screened in 2024 compared to previous years was in the individual titles. Last year’s most frequently screened films, The Cabinet Of Dr Caligari (40 separate showings),  Metropolis (34) and Man With A Movie Camera (24) were nowhere to be seen in 2024. Instead, this years screenings were dominated by Buster Keaton with 39 screenings for The General, 33 for Sherlock Jr

Metropolis (34) and Man With A Movie Camera (24) were nowhere to be seen in 2024. Instead, this years screenings were dominated by Buster Keaton with 39 screenings for The General, 33 for Sherlock Jr  and 30 for Steamboat Bill Jr. This was thanks largely to nationwide screenings of each of these films at numerous Picture House chain cinemas. (And keeping very much in the classic comedy vein, mention also has to be made of Neil Brand’s Laurel and Hardy show which included two of L&H’s classic short comedies and which was on the road for much of the year with at least 29 performances.)

and 30 for Steamboat Bill Jr. This was thanks largely to nationwide screenings of each of these films at numerous Picture House chain cinemas. (And keeping very much in the classic comedy vein, mention also has to be made of Neil Brand’s Laurel and Hardy show which included two of L&H’s classic short comedies and which was on the road for much of the year with at least 29 performances.)

In fourth spot, the same as last year, with 27 screenings was perennial favourite Nosferatu which always gets a boost with multiple screenings around Halloween. Then it’s a long way down to the next most popular screenings;

8 screenings – Safety Last, The Lodger

7 screenings – Sunrise

6 screenings – Cabinet of Dr Caligari

5 Screenings – Pandora’s Box, Piccadilly, Battleship Potemkin

4 screenings – The Mark of Zorro

3 screenings – Phantom f the Opera, Haxan, The Cat and the Canary, Metropolis, The Golem, Shooting Stars

Screening Venues

Given that the number of films screened in 2024 remained exactly the same as in 2023 it is not surprising that the number of silent film venues also remained very similar to last year, standing at 136 compared to the 137 different venues for the previous year.

But the big difference compared to previous years is that the BFI Southbank has lost its place as the country’s leading venue for silent film. That honour

But the big difference compared to previous years is that the BFI Southbank has lost its place as the country’s leading venue for silent film. That honour  now goes to the Cinema Museum in Lambeth which put on 45 silent film events last year, most of which were organised by the Kennington Bioscope (38). As usual, the KenBio had a wonderfully eclectic programme of rarities and the rarely screened, including two silent film weekends. In contrast, BFI Southbank could only manage 41 screenings which, although they included a few rarely screened gems, once again was over-reliant on

now goes to the Cinema Museum in Lambeth which put on 45 silent film events last year, most of which were organised by the Kennington Bioscope (38). As usual, the KenBio had a wonderfully eclectic programme of rarities and the rarely screened, including two silent film weekends. In contrast, BFI Southbank could only manage 41 screenings which, although they included a few rarely screened gems, once again was over-reliant on  wheeling out a somewhat tired range of too often screened ‘workhorses’ such as Nosferatu, Pandora’s Box, The General, Safety Last and Battleship Potemkin, often without even live musical accompaniment. Surely what is supposed to be the country’s premier repertory cinema with an unrivaled film archive behind it can do better than this.

wheeling out a somewhat tired range of too often screened ‘workhorses’ such as Nosferatu, Pandora’s Box, The General, Safety Last and Battleship Potemkin, often without even live musical accompaniment. Surely what is supposed to be the country’s premier repertory cinema with an unrivaled film archive behind it can do better than this.

In third place was the Bo’ness Hippodrome with 19 screenings, once again coming in with a very strong film programme both at their annual HippFest and their short autumn season. Coming in fourth with 12 screenings was The Prince Charles Cinema in London, although with a very limited programme of Caligari, SafetyLast and Nosferatu. This is another venue that could do with becoming a little more adventurous in its programming. Next up with 11 screenings was The Rex Cinema in Wareham with the second edition of their ambitious Silent Film

In third place was the Bo’ness Hippodrome with 19 screenings, once again coming in with a very strong film programme both at their annual HippFest and their short autumn season. Coming in fourth with 12 screenings was The Prince Charles Cinema in London, although with a very limited programme of Caligari, SafetyLast and Nosferatu. This is another venue that could do with becoming a little more adventurous in its programming. Next up with 11 screenings was The Rex Cinema in Wareham with the second edition of their ambitious Silent Film  Weekender. Sharing sixth spot was The Watershed in Bristol and Wilton’s Music Hall in London with 10 screenings apiece, with the Watershed focused mainly on Bristol’s Slapstick Festival and Wilton’s benefiting from the efforts of the Lucky Dog Picturehouse.

Weekender. Sharing sixth spot was The Watershed in Bristol and Wilton’s Music Hall in London with 10 screenings apiece, with the Watershed focused mainly on Bristol’s Slapstick Festival and Wilton’s benefiting from the efforts of the Lucky Dog Picturehouse.

A shout out also to the Morecambe Winter Gardens with screenings from Northern Silents and Brentford’s Musical Museum frequently playing host to silent film organist Donald MacKenzie, with 8 screenings each.

Other regular venues included;

5 screenings – Palace Broadstairs, Barbican London

4 screenings – Bristol Beacon

3 screenings – York National Centre For Early Music, Storeyhouse Chester, BIMI London, Garden Cinema London, Hull Truck Theatre, Oxford Ultimate

Mention must also go to the Picture House Chain for their more than 80 screenings of the three Buster Keaton films.

Silent Film Highlights of 2024

The year started in January with several screenings of Sunrise: A Song Of Two Humans (1927) at BFI Southbank, albeit with recorded scores. Of more interest was their screening of Lubitsch’s wonderful adaption of Oscar Wilde classic Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925). The Kennington Bioscope got off a strong start to the year with a very rare screening of the Photoplay Productions version of Phantom of the Opera (1925) as well as Heart O’ The Hills (1919) starring a very out of character Mary Pickford in a hard-hitting rural melodrama. BIMI in London had what looked to be a fascinating (and sold out!) presentation, The Coming Of Cinema To Istanbul, an illustrated talk by a leading Turkish film

The year started in January with several screenings of Sunrise: A Song Of Two Humans (1927) at BFI Southbank, albeit with recorded scores. Of more interest was their screening of Lubitsch’s wonderful adaption of Oscar Wilde classic Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925). The Kennington Bioscope got off a strong start to the year with a very rare screening of the Photoplay Productions version of Phantom of the Opera (1925) as well as Heart O’ The Hills (1919) starring a very out of character Mary Pickford in a hard-hitting rural melodrama. BIMI in London had what looked to be a fascinating (and sold out!) presentation, The Coming Of Cinema To Istanbul, an illustrated talk by a leading Turkish film  historian including a selection of early films of Constantinople/Istanbul while the Prince Charles in London started the year with Safety Last (1923) and The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) and Barbican London had a now all too rare silent treat with Haxan; Witchcraft Through The Ages (1922). February saw multiple screenings of The General (1926) and Sherlock Jr (1924) at Picture House cinemas. BFI Southbank had Valentino in Blood And Sand (1922) and Clara Bow in Get Your Man (1927) both

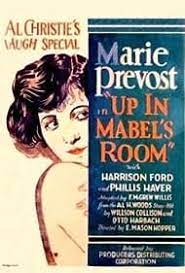

historian including a selection of early films of Constantinople/Istanbul while the Prince Charles in London started the year with Safety Last (1923) and The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) and Barbican London had a now all too rare silent treat with Haxan; Witchcraft Through The Ages (1922). February saw multiple screenings of The General (1926) and Sherlock Jr (1924) at Picture House cinemas. BFI Southbank had Valentino in Blood And Sand (1922) and Clara Bow in Get Your Man (1927) both  directed by Dorothy Arzner. London’s Garden Cinema screened The Seashell and the Clergyman (1928) and The Smiling Madame Beudet (1923) as part of a Women And Surrealism event. But the month’s principal event was Bristol’s Slapstick Festival, highlights of which included the wonderful Beatrice Lille in Exit Smiling (1926), Marie Prevost in Up In Mabel’s Room (1926) and Norma Talmadge in Kiki (1926). Also in Bristol, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) screened at St George’s with a full orchestral accompaniment. Meanwhile in London the Kennington

directed by Dorothy Arzner. London’s Garden Cinema screened The Seashell and the Clergyman (1928) and The Smiling Madame Beudet (1923) as part of a Women And Surrealism event. But the month’s principal event was Bristol’s Slapstick Festival, highlights of which included the wonderful Beatrice Lille in Exit Smiling (1926), Marie Prevost in Up In Mabel’s Room (1926) and Norma Talmadge in Kiki (1926). Also in Bristol, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) screened at St George’s with a full orchestral accompaniment. Meanwhile in London the Kennington  Bioscope showcased Pola Negri in Lubitsch’s Madame Dubarry (1919) while the Austrian Cultural Forum had Part One of Fritz Lange’s teutonic epic Die Nibelungen (1924). In March we got Part Two of Die Nibelungen (1924) at the Austrian Cultural Forum plus the somewhat overblown melodrama Stella Dallas (1925) at the Fleapit Cinema Club in Westerham. Neil Brand provided accompaniment for three outings of Piccadilly (1929) in Ludlow, Hereford and Malvern while Stephen Horne was on hand at BFI Southbank to accompany

Bioscope showcased Pola Negri in Lubitsch’s Madame Dubarry (1919) while the Austrian Cultural Forum had Part One of Fritz Lange’s teutonic epic Die Nibelungen (1924). In March we got Part Two of Die Nibelungen (1924) at the Austrian Cultural Forum plus the somewhat overblown melodrama Stella Dallas (1925) at the Fleapit Cinema Club in Westerham. Neil Brand provided accompaniment for three outings of Piccadilly (1929) in Ludlow, Hereford and Malvern while Stephen Horne was on hand at BFI Southbank to accompany  William Wyler’s classic western Hell’s Heroes (1929). Then it is off up to Scotland for the Hippodrome Silent Film Festival in Bo’ness. There were rare screenings for both silent and talkie versions of classic British train drama The Flying Scotsman (1929). Clara Bow flaunted her ‘It’ in Mantrap (1926) while Mary Pickford played dual roles in deeply dark melodrama Stella Maris (1918). On a lighter note was the little known but utterly charming Ukraine comedy Adventures of a Half Ruble (1929) with some of the best child acting ever put on screen. Another rarity was The Norrtull Gang (1923), a sort of silent Swedish precursor to Sex In The

William Wyler’s classic western Hell’s Heroes (1929). Then it is off up to Scotland for the Hippodrome Silent Film Festival in Bo’ness. There were rare screenings for both silent and talkie versions of classic British train drama The Flying Scotsman (1929). Clara Bow flaunted her ‘It’ in Mantrap (1926) while Mary Pickford played dual roles in deeply dark melodrama Stella Maris (1918). On a lighter note was the little known but utterly charming Ukraine comedy Adventures of a Half Ruble (1929) with some of the best child acting ever put on screen. Another rarity was The Norrtull Gang (1923), a sort of silent Swedish precursor to Sex In The  City. In contrast, The Organist at St Vitus Cathedral was a brooding but brilliant Czech melodrama with a stunning accompaniment from Maud Nelissen. Then there was Stephen Horne and Frank Bockius accompanying The Wind (1928) and John Sweeney playing while Chinese superstar Li Li-li fizzed with vitality in Queen Of Sports (1934). All in all, probably the strongest HippFest programme we’ve attended. Even the illustrated talks were superb. Who will forget The Wonderful World Of Eve’s Film Review. Meanwhile, back in London the KenBio were puzzling over Ralph Ince mystery thriller The Argyle Case (1917) while at the Rio in Dalston there was a slice of controversy with Ivor Novello and Mabel Poulten in The Constant Nymph (1928) and up in Birmingham it was religious epic time with De Mille’s King of Kings (1927).

City. In contrast, The Organist at St Vitus Cathedral was a brooding but brilliant Czech melodrama with a stunning accompaniment from Maud Nelissen. Then there was Stephen Horne and Frank Bockius accompanying The Wind (1928) and John Sweeney playing while Chinese superstar Li Li-li fizzed with vitality in Queen Of Sports (1934). All in all, probably the strongest HippFest programme we’ve attended. Even the illustrated talks were superb. Who will forget The Wonderful World Of Eve’s Film Review. Meanwhile, back in London the KenBio were puzzling over Ralph Ince mystery thriller The Argyle Case (1917) while at the Rio in Dalston there was a slice of controversy with Ivor Novello and Mabel Poulten in The Constant Nymph (1928) and up in Birmingham it was religious epic time with De Mille’s King of Kings (1927).

April opened with an early slice of Film Noir in the shape of Sternberg’s Docks Of New York (1928) at Bristol’s Watershed accompanied by Meg Morley. Jonny Best and the Northern Silents team were busy in Kendal and Manchester putting on a western double bill of The General (1926) and The Great Train Robbery (1903). They also screened Chicago (1927) in Chester and Metropolis (1927) in Pudsey. Back in London the KenBio had more drama with newspaper thriller The Last Edition (1925) prior to their Silent Film Weekend kicking

April opened with an early slice of Film Noir in the shape of Sternberg’s Docks Of New York (1928) at Bristol’s Watershed accompanied by Meg Morley. Jonny Best and the Northern Silents team were busy in Kendal and Manchester putting on a western double bill of The General (1926) and The Great Train Robbery (1903). They also screened Chicago (1927) in Chester and Metropolis (1927) in Pudsey. Back in London the KenBio had more drama with newspaper thriller The Last Edition (1925) prior to their Silent Film Weekend kicking  off. That included the wonderfully funny British comedy Not For Sale (1924), Italian disaster epic The Last Days of Pompeii (1913) and German historic adventure melodrama Taras Bulba (1924). The month ended with the ever so stylish Anna May Wong in Pavement Butterfly (1929) at BFI Southbank. In May the KenBio kicked off with cross-dressing comedy Charley’s Aunt (1925). Birmingham’s Flatpack Festival had a real oddity in Hellbound Train (1930), the work of two African-American evangelists dramatising the sins of the Jazz Age! Harpist Elizabeth Jane

off. That included the wonderfully funny British comedy Not For Sale (1924), Italian disaster epic The Last Days of Pompeii (1913) and German historic adventure melodrama Taras Bulba (1924). The month ended with the ever so stylish Anna May Wong in Pavement Butterfly (1929) at BFI Southbank. In May the KenBio kicked off with cross-dressing comedy Charley’s Aunt (1925). Birmingham’s Flatpack Festival had a real oddity in Hellbound Train (1930), the work of two African-American evangelists dramatising the sins of the Jazz Age! Harpist Elizabeth Jane  Baldry made a rare but welcome appearance in Bridgewater accompanying The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926) while organist Donald MacKenzie accompanied the wonderful Marion Davies in Show People (1928) at the Brentford Musical Museum. While at Wilton’s Music Hall the Lucky Dog Picture House kicked off their season with Harold Lloyd in Girl Shy (1924) and BFI Southbank showcased the talents of Betty Balfour, ‘Britain’s

Baldry made a rare but welcome appearance in Bridgewater accompanying The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926) while organist Donald MacKenzie accompanied the wonderful Marion Davies in Show People (1928) at the Brentford Musical Museum. While at Wilton’s Music Hall the Lucky Dog Picture House kicked off their season with Harold Lloyd in Girl Shy (1924) and BFI Southbank showcased the talents of Betty Balfour, ‘Britain’s  own queen of happiness’, in Vagabond Queen (1929). June was a good month for Northern Silents with screenings of The Kid (1921) and The Lost World (1925) as well as some Melies delights in Morecambe, Diary of a Lost Girl (1929) in York, and The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) in Manchester. The Lucky Dog Picture House also got into its stride at Wilton’s Music Hall with Pandora’s Box (1929), The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and Shooting Stars (1929).

own queen of happiness’, in Vagabond Queen (1929). June was a good month for Northern Silents with screenings of The Kid (1921) and The Lost World (1925) as well as some Melies delights in Morecambe, Diary of a Lost Girl (1929) in York, and The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) in Manchester. The Lucky Dog Picture House also got into its stride at Wilton’s Music Hall with Pandora’s Box (1929), The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and Shooting Stars (1929).

July opened with a rare screening of time-travelling romance The Man Without Desire (1923), “one of the stranger films to emerge from Britain in the 1920s”, at BIMI in London with an impressive accompaniment by Costas Fotopoulos. Also in London, BFI Southbank screened Light of Asia (1925), the story of Prince Siddhartha Gautama the man who became the Buddha.while Lucky Dog Picture House screened A Cottage On Dartmoor (1928), Sherlock jr (1924), Underground (1928) and Piccadilly (1929). Down in Bristol we got an opportunity to see

July opened with a rare screening of time-travelling romance The Man Without Desire (1923), “one of the stranger films to emerge from Britain in the 1920s”, at BIMI in London with an impressive accompaniment by Costas Fotopoulos. Also in London, BFI Southbank screened Light of Asia (1925), the story of Prince Siddhartha Gautama the man who became the Buddha.while Lucky Dog Picture House screened A Cottage On Dartmoor (1928), Sherlock jr (1924), Underground (1928) and Piccadilly (1929). Down in Bristol we got an opportunity to see  Japanese heart throb Sessue Hayakawa in The Dragon Painter (1919). August was something of a lean month, but the high-point was undoubtedly Louise Brooks and Evelyn Brent in Love ’Em and Leave ’Em (1926) at BFI Southbank. There was also my favourite Keaton, The Navigator (1924), at Pound Arts, Corsham, Piccadilly (1929) at the Brentford Musical Museum and Underground (1928) in Chichester. September kicked off with Shooting Stars (1928) at BFI Southbank

Japanese heart throb Sessue Hayakawa in The Dragon Painter (1919). August was something of a lean month, but the high-point was undoubtedly Louise Brooks and Evelyn Brent in Love ’Em and Leave ’Em (1926) at BFI Southbank. There was also my favourite Keaton, The Navigator (1924), at Pound Arts, Corsham, Piccadilly (1929) at the Brentford Musical Museum and Underground (1928) in Chichester. September kicked off with Shooting Stars (1928) at BFI Southbank  and they doubled down also with Julien Duvivier’s stunning Poil de Carotte (1925) with some amazing child actors plus live accompaniment from Stephen Horne. The KenBio screened John Ford’s epic western The Iron Horse (1924) with a welcome and sadly now all too rare introduction by Kevin Brownlow. But the big event of the month was the seceond Wareham Silent Film Weekender. Eleven screen events, with a high canine quota this year

and they doubled down also with Julien Duvivier’s stunning Poil de Carotte (1925) with some amazing child actors plus live accompaniment from Stephen Horne. The KenBio screened John Ford’s epic western The Iron Horse (1924) with a welcome and sadly now all too rare introduction by Kevin Brownlow. But the big event of the month was the seceond Wareham Silent Film Weekender. Eleven screen events, with a high canine quota this year  so lots of Rin Tin Tin and his numerous rivals such as Fearless The Dog. But other screenings also included two rare Hitchcocks, The Ring (1927) and Champagne (1928), plus John Barrymore as The Loveable Rogue (1927). Pianist Meg Morley put in a shift playing for over half of the screenings. Lastly there was a welcome showing of Haxan (1922) on the very big screen at Bristol’s IMAX with accompaniment from Stephen Horne.

so lots of Rin Tin Tin and his numerous rivals such as Fearless The Dog. But other screenings also included two rare Hitchcocks, The Ring (1927) and Champagne (1928), plus John Barrymore as The Loveable Rogue (1927). Pianist Meg Morley put in a shift playing for over half of the screenings. Lastly there was a welcome showing of Haxan (1922) on the very big screen at Bristol’s IMAX with accompaniment from Stephen Horne.

October was a busy month for Northern Silents with Metropolis (1927) screening in Kendal, The Thief Of Bagdad (1924) in Hull, The Mark Of Zorro ( 1920) in Chester, The Ancient Law (1923) in London and York, The City Without Jews (1924) also in York and The Cat and the Canary (1927) in Leeds. The Cine Lumiere in London had a real rarity with a Georgian western, The Rider From The Wild West (1925), which was stunning, especially with a knockout accompaniment from John Sweeney. Not to be outdone in the rarity stakes, BFI Southbank countered with Shor and Shorshor (1926) the first Armenian comedy to be released on the screen. Sadly this year’s London Film Festival had but one silent screening, a rather under-powered triple bill of Sherlock Holmes shorts starring Eille

October was a busy month for Northern Silents with Metropolis (1927) screening in Kendal, The Thief Of Bagdad (1924) in Hull, The Mark Of Zorro ( 1920) in Chester, The Ancient Law (1923) in London and York, The City Without Jews (1924) also in York and The Cat and the Canary (1927) in Leeds. The Cine Lumiere in London had a real rarity with a Georgian western, The Rider From The Wild West (1925), which was stunning, especially with a knockout accompaniment from John Sweeney. Not to be outdone in the rarity stakes, BFI Southbank countered with Shor and Shorshor (1926) the first Armenian comedy to be released on the screen. Sadly this year’s London Film Festival had but one silent screening, a rather under-powered triple bill of Sherlock Holmes shorts starring Eille  Norwood. Much more of an event was a screening of Hitchcock’s The Manxman (1929) in Polperro in Cornwall, the village where the film was actually filmed. The KenBio wrapped up the month with a screening of The Bat (1926), one of the first ‘old dark house’ mystery thrillers. November saw a rare outing for one of the few surviving Cecil Hepworth feature length

Norwood. Much more of an event was a screening of Hitchcock’s The Manxman (1929) in Polperro in Cornwall, the village where the film was actually filmed. The KenBio wrapped up the month with a screening of The Bat (1926), one of the first ‘old dark house’ mystery thrillers. November saw a rare outing for one of the few surviving Cecil Hepworth feature length  films, Helen of Four Gates (1920) in Heptonstall, the Yorkshire village where much of it was filmed. The KenBio’s Silent Comedy Weekend featured several rarities including a Pat and Patachon comedy The Mannequins (1929), Syd Chaplin in Oh What A Nurse (1926) and horror-comedy-thriller The Gorilla (1927) but the undoubted highlight had to be The Patsy (1928) with Marion Davies out Gish-ing Lillian Gish. Acclaimed accompanists Minima were on the road for much of the month with multiple screenings of The Lodger (1927) and Nosferatu (1922). Pianist Lillian Henley accompanied The Black Pirate (1926) in both Broadstairs and Colchester while Jonny Best and

films, Helen of Four Gates (1920) in Heptonstall, the Yorkshire village where much of it was filmed. The KenBio’s Silent Comedy Weekend featured several rarities including a Pat and Patachon comedy The Mannequins (1929), Syd Chaplin in Oh What A Nurse (1926) and horror-comedy-thriller The Gorilla (1927) but the undoubted highlight had to be The Patsy (1928) with Marion Davies out Gish-ing Lillian Gish. Acclaimed accompanists Minima were on the road for much of the month with multiple screenings of The Lodger (1927) and Nosferatu (1922). Pianist Lillian Henley accompanied The Black Pirate (1926) in both Broadstairs and Colchester while Jonny Best and  Northern Silents brought Battleship Potemkin (1925) to life in Morecambe. BFI Southbank provided some hair-raising moments with their Girls Without Nerves: Action Women of the Silent Era compilation while there

Northern Silents brought Battleship Potemkin (1925) to life in Morecambe. BFI Southbank provided some hair-raising moments with their Girls Without Nerves: Action Women of the Silent Era compilation while there  was a strange tale of science fiction, love and death in the ring with Tragedy at the Circus Royal (1928) at the KenBio. December opened with a somewhat salacious epic, Quo Vadis? (1924), at BFI Southbank. The KenBio ended their year with another moving circus-based drama, Sideshow (1928) with a superb performance by small actor ‘Little Billy’ Rhodes. At the Brentford Musical Museum, Mary Pickford played Cinderella (1914) while the year finished on the BIGGEST of screens with Nosferatu (1922) playing at the BFI IMAX in London.

was a strange tale of science fiction, love and death in the ring with Tragedy at the Circus Royal (1928) at the KenBio. December opened with a somewhat salacious epic, Quo Vadis? (1924), at BFI Southbank. The KenBio ended their year with another moving circus-based drama, Sideshow (1928) with a superb performance by small actor ‘Little Billy’ Rhodes. At the Brentford Musical Museum, Mary Pickford played Cinderella (1914) while the year finished on the BIGGEST of screens with Nosferatu (1922) playing at the BFI IMAX in London.

Our Top Ten Of The Year

So, what then were our ten favourite silent films of the year (not necessarily the ten best films, but those screenings and accompaniment which we most enjoyed). They are as follows (by screening date order);

Exit Smiling (Dir. Sam Taylor, US, 1926) 14 February Slapstick Festival at Watershed Bristol with live piano accompaniment from Daan van den Hurk. Its strange how you can watch a film a couple of times and be underwhelmed and then suddenly on a further viewing it grabs you. A perfect example here, largely thanks to Beatrice Lille’s performance, funny, moving and ultimately with a hint of tragedy as her dreams of fame and the love of Jack Pickford go unfulfilled. And with a nice accompaniment from Daan van den Hurk which nicely complemented both the frantic comedy and the gentle pathos.

Exit Smiling (Dir. Sam Taylor, US, 1926) 14 February Slapstick Festival at Watershed Bristol with live piano accompaniment from Daan van den Hurk. Its strange how you can watch a film a couple of times and be underwhelmed and then suddenly on a further viewing it grabs you. A perfect example here, largely thanks to Beatrice Lille’s performance, funny, moving and ultimately with a hint of tragedy as her dreams of fame and the love of Jack Pickford go unfulfilled. And with a nice accompaniment from Daan van den Hurk which nicely complemented both the frantic comedy and the gentle pathos.

Up In Mabel’s Room (Dir. E. Mason Hopper US, 1926) 15 February Slapstick Festival at Watershed Bristol with live piano accompaniment from Daan van den Hurk. Marie Prevost shines as the scatty, change-of-mind flapper heroine, a woman on a mission to remarry the man she mistakenly divorced. And Harrison Ford (not that one!) also shinesas the clueless sap she has re-set her mind on. Daan van den Hurk, putting in quite a shift at the festival, again nicely captures the knockabout tone of the film.

Up In Mabel’s Room (Dir. E. Mason Hopper US, 1926) 15 February Slapstick Festival at Watershed Bristol with live piano accompaniment from Daan van den Hurk. Marie Prevost shines as the scatty, change-of-mind flapper heroine, a woman on a mission to remarry the man she mistakenly divorced. And Harrison Ford (not that one!) also shinesas the clueless sap she has re-set her mind on. Daan van den Hurk, putting in quite a shift at the festival, again nicely captures the knockabout tone of the film.

Adventures Of A Half Ruble (Dir. Aksel Lundin, USSR, 1929) 21 March Hippodrome Silent Film Festival with live piano accompaniment from John Sweeney. Made in the Soviet Ukraine but set in Imperial Russia, the film was intended to educate a young audience about class struggle. Propaganda, certainly, and often somewhat heavy handed, but the film has some amazing performances from its largely child orphan cast. Also featuring some breathtaking cinematography with stunning views of Kyiv and the Dneiper River. A delight from beginning to end with equally brilliant accompaniment from pianist John Sweeney.

Adventures Of A Half Ruble (Dir. Aksel Lundin, USSR, 1929) 21 March Hippodrome Silent Film Festival with live piano accompaniment from John Sweeney. Made in the Soviet Ukraine but set in Imperial Russia, the film was intended to educate a young audience about class struggle. Propaganda, certainly, and often somewhat heavy handed, but the film has some amazing performances from its largely child orphan cast. Also featuring some breathtaking cinematography with stunning views of Kyiv and the Dneiper River. A delight from beginning to end with equally brilliant accompaniment from pianist John Sweeney.

The Organist of St Vitus Cathedral (Dir. Martin Fric, Cz,1929) 23 March Hippodrome Silent Film Festival with live musical accompaniment from Maud Nelissen. A little known but gripping melodrama. Slow, almost ponderous, at times the film exudes a sense of unease and builds to a gripping climax but that is but half the story. With amazing expressionist cinematography (we could almost be in Jean Epstein territory) and art direction and compelling central performances, this was a masterpiece. And pianist/organist Maud Nelissen simply added to the film’s brilliance with accompaniment that was at times necessarily minimalist and at other times thunderous to reflect the changing tone of the story.

The Organist of St Vitus Cathedral (Dir. Martin Fric, Cz,1929) 23 March Hippodrome Silent Film Festival with live musical accompaniment from Maud Nelissen. A little known but gripping melodrama. Slow, almost ponderous, at times the film exudes a sense of unease and builds to a gripping climax but that is but half the story. With amazing expressionist cinematography (we could almost be in Jean Epstein territory) and art direction and compelling central performances, this was a masterpiece. And pianist/organist Maud Nelissen simply added to the film’s brilliance with accompaniment that was at times necessarily minimalist and at other times thunderous to reflect the changing tone of the story.

The Norrtull Gang (Dir Per Lindberg, Swe, 1923 ) 24 March Hippodrome Silent Film Festival with live musical accompaniment from John Sweeney. A sort of silent Swedish precursor to Sex In The City, funny but with a serious side regarding female friends trying to navigate their careers in the male-dominated office culture, as relevant today (and perhaps even more so) as when it was made. And with just the lightest of touches pianist John Sweeney added so much to enjoyment of this delightful little film. (And there is another rare chance to catch The Norrtull Gang at Bristol’s Slapstick Festival on 12 February)

The Norrtull Gang (Dir Per Lindberg, Swe, 1923 ) 24 March Hippodrome Silent Film Festival with live musical accompaniment from John Sweeney. A sort of silent Swedish precursor to Sex In The City, funny but with a serious side regarding female friends trying to navigate their careers in the male-dominated office culture, as relevant today (and perhaps even more so) as when it was made. And with just the lightest of touches pianist John Sweeney added so much to enjoyment of this delightful little film. (And there is another rare chance to catch The Norrtull Gang at Bristol’s Slapstick Festival on 12 February)

The Wind (Dir. Victor Sjöström, US. 1928) 24 March Hippodrome Silent Film Festival with live musical accompaniment from Stephen Horne and Frank Bockius. It doesn’t matter how many times I see this film, its still brilliant. Lillian Gish’s wonderful portrayal of the delicate Letty, overwhelmed by the dust and the wind, Lars Hanson as the bovine and uncomprehending Lige and Montague Love as the ever so sleazy Wirt Roddy, always so stylishly brushing the dust from his clothes. But with Messers Horne and Bockius providing accompaniment the film is taken to another level. You can almost feel the wind on your face and the dust in your eyes.

The Wind (Dir. Victor Sjöström, US. 1928) 24 March Hippodrome Silent Film Festival with live musical accompaniment from Stephen Horne and Frank Bockius. It doesn’t matter how many times I see this film, its still brilliant. Lillian Gish’s wonderful portrayal of the delicate Letty, overwhelmed by the dust and the wind, Lars Hanson as the bovine and uncomprehending Lige and Montague Love as the ever so sleazy Wirt Roddy, always so stylishly brushing the dust from his clothes. But with Messers Horne and Bockius providing accompaniment the film is taken to another level. You can almost feel the wind on your face and the dust in your eyes.

Docks of New York (Dir. Josef von Sternberg, US, 1928) 6 April The Watershed, Bristol with live musical accompaniment by Meg Morley. Think that Film Noir is a genre of the 1940s? Think again! For here was a stunning silent example from von Sternberg with George Bancroft superb as tough ship’s stoker Bill, Betty Compson as Mae, a “tough cookie” prostitute and not forgetting the always excellent Olga Baclanova. inhabiting a dark, gritty world of flophouses, gin-mills and seedy docks. But what’s this? Just the hint of a happy ending. Gripping stuff, and all graced with Meg Morley‘s superb accompaniment.

Docks of New York (Dir. Josef von Sternberg, US, 1928) 6 April The Watershed, Bristol with live musical accompaniment by Meg Morley. Think that Film Noir is a genre of the 1940s? Think again! For here was a stunning silent example from von Sternberg with George Bancroft superb as tough ship’s stoker Bill, Betty Compson as Mae, a “tough cookie” prostitute and not forgetting the always excellent Olga Baclanova. inhabiting a dark, gritty world of flophouses, gin-mills and seedy docks. But what’s this? Just the hint of a happy ending. Gripping stuff, and all graced with Meg Morley‘s superb accompaniment.

The Iron Horse (Dir. John Ford, US, 1924) 11 September Kennington Bioscope at The Cinema Museum, London with live piano accompaniment from Cyrus Gabrysch. Another perennial favourite which gets better with every viewing. Epics don’t get any bigger than this. With already more than 50 B-movies to his name director Ford suddenly shot to A-Movie status with this sweeping slice of railroad building history. And not only did the film come with equally epic piano accompaniment from Cyrus Gabrysch but also with a welcome and sadly now all too rare introduction by renowned film historian Kevin Brownlow.

The Iron Horse (Dir. John Ford, US, 1924) 11 September Kennington Bioscope at The Cinema Museum, London with live piano accompaniment from Cyrus Gabrysch. Another perennial favourite which gets better with every viewing. Epics don’t get any bigger than this. With already more than 50 B-movies to his name director Ford suddenly shot to A-Movie status with this sweeping slice of railroad building history. And not only did the film come with equally epic piano accompaniment from Cyrus Gabrysch but also with a welcome and sadly now all too rare introduction by renowned film historian Kevin Brownlow.

The Rider From The Wild West (Dir. Aleksandre Tsutsunava, Geo, 1925) 4 October Presented as part of the London Georgian Film Festival at the Cine Lumiere, London with live piano accompaniment by John Sweeney. Based upon real-life as horse-riders from Georgia did actually travel to America to work in Wild West circus shows, the film is as much about the women left behind and the hypocritical attitudes towards male and female infidelity (actual or suspected) of the era. The cinematography is incredible, especially in the action scenes and there was an actual US style three ring circus built in Georgia (and looking very authentic) for the film. With scenes set both in traditional Georgia and jazz-era America pianist John Sweeney got ample opportunity to demonstrate his many musical styles which he did to great effect.

The Rider From The Wild West (Dir. Aleksandre Tsutsunava, Geo, 1925) 4 October Presented as part of the London Georgian Film Festival at the Cine Lumiere, London with live piano accompaniment by John Sweeney. Based upon real-life as horse-riders from Georgia did actually travel to America to work in Wild West circus shows, the film is as much about the women left behind and the hypocritical attitudes towards male and female infidelity (actual or suspected) of the era. The cinematography is incredible, especially in the action scenes and there was an actual US style three ring circus built in Georgia (and looking very authentic) for the film. With scenes set both in traditional Georgia and jazz-era America pianist John Sweeney got ample opportunity to demonstrate his many musical styles which he did to great effect.

The Sideshow (Dir. Erle C. Kenton, US, 1928 ) 11 December Kennington Bioscope at The Cinema Museum, London with live piano accompaniment from Cyrus Gabrysch. It was an epic labour of love by the KenBio‘s Michelle Facey to bring about this screening, showcasing the talents of one of her favourite stars, the lovely but tragic Marie Prevost. Although Ms Prevost is excellent the film is also particularly noteworthy for its rare presentation of a little person in a sympathetic adult role, played by ‘Little Billy’ Rhodes in his one starring role with his love for Marie Prevost’s circus performer going un-noticed and unrequited. Pianist Cyrus Gabrysch was again on hand to provide a thoughtful and sympathetic accompaniment.

The Sideshow (Dir. Erle C. Kenton, US, 1928 ) 11 December Kennington Bioscope at The Cinema Museum, London with live piano accompaniment from Cyrus Gabrysch. It was an epic labour of love by the KenBio‘s Michelle Facey to bring about this screening, showcasing the talents of one of her favourite stars, the lovely but tragic Marie Prevost. Although Ms Prevost is excellent the film is also particularly noteworthy for its rare presentation of a little person in a sympathetic adult role, played by ‘Little Billy’ Rhodes in his one starring role with his love for Marie Prevost’s circus performer going un-noticed and unrequited. Pianist Cyrus Gabrysch was again on hand to provide a thoughtful and sympathetic accompaniment.

And if we had our feet held to the fire and had to pick just one film of the year? As usual, such a difficult choice, but if we had to pick then it would probably be The Organist of St Vitus Cathedral but with The Rider From The Wild West and The Norrtull Gang giving it a close run for its money.

And A Few Misses Of The Year!

So, what were the biggest misses of the year. Well, unusually we didn’t see a single film which we wanted to get up and walk out of, either because the film was awful or the accompaniment didn’t work. Most of our misses this year were missed opportunities to see films (due in large part to the renewed patter of tiny canine paws in our household). So no Wareham Silent Film Weekender this year and very little of KenBio‘s Silent Film Weekend. We also sadly missed out on seeing The Manxman screened in the very village it was filmed in and we didn’t get to see any of Northern Silents extensive programme. Oh well, maybe next year!

And that pretty well wraps up this review of the year, other than to express, as usual, our thanks to all of those venues, programmers, projectionists, accompanists, hosts, speakers and volunteers who give so generously of their time, energies and skills to make these silent events happen. Your efforts as always are really appreciated.